HTTP/2 Server Push

The new version of the HTTP protocol, HTTP/2 lets the server to push content to the client before the client requests the particular content. There are many other modifications in the protocol if we compare the previous version 1.1 with the new version 2, but in this article, I will focus on the push functionality. I will discuss briefly how it can be used in a servlet, and I will also discuss a bit about how to test and see that it really works at all or not. Before writing this article my original intention was to create a demonstration of HTTP/2 showing how faster the sample page load is with the push than it is without. It is going to be one chapter in my video tutorial that is published by PACKT. During the development of the sample application I faced several problems, I have read some tutorials and debugged the sample code a bit gathering experience. In this article, I share this experience with you. That way this article is a bit more than just a simple introductory tutorial. Nevertheless, it is also a bit longer, so TLDR; if you are impatient.

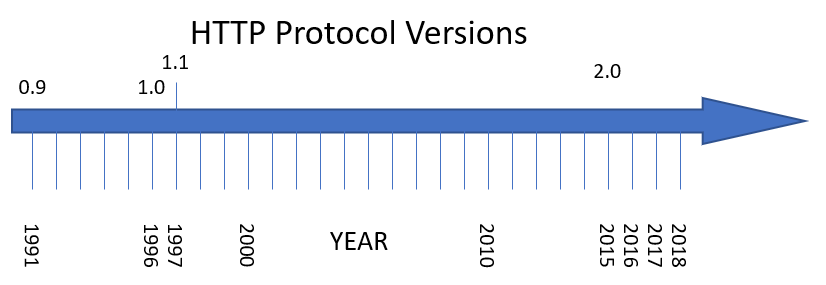

HTTP versions

HTTP/2 is a new version of the HTTP protocol. The protocol had three versions prior to 2. They were 0.9, 1.0 and 1.1. The first one was only an experiment starting in 1991. The first real version was 1.0 released in 1996. This was the version that you probably met if you were using the internet that time and you still remember the Mosaic browser. This version was soon followed by the version 1.1 next year, 1997. The major difference between 1.0 and 1.1 was the Host

HTTP 1.1

Both versions 1.0 and 1.1 are extremely simple. The client opens a TCP channel to the server and writes the request into it as a plain text. The request starts with a request line, it is followed by header lines, an empty line and the body of the request. The body may be binary. The response has the same structure except the first line is not a request specific line, but rather a response obviously.

Imho, the simple approach was extremely important these days because it was inevitable to aid the spread and use of the protocol. You can find this type of pattern in the industry in different areas. This is how the world is developing in an agile way. First, you develop something simple that works and then you go on making it more and more complex as the environment requires it to be more powerful longing for more complexity. Making a long-shot and aiming for the complex and perfect solution the first time usually does not work. If you remember the film series Star Wars you know that death stars are never finished and they are razed at the end. But it does not mean that the simple version that we start with has no problems.

HTTP/1.1 problems

HTTP/1.1 had a lot of problems. A real Englishman could say it was far from optimal using the network. It was wasting bandwidth. Early times when HTTP was invented a web page was text. Today it is text, CSS, JavaScript, images, sounds, videos and digitized smell, taste, and touch samples not to mention the direct neural stimulation command files. These last content types following videos in this taxative list are still rare but you should be prepared and that is what HTTP/2 is aiming. Preparing for the future. With HTTP/1.1 the browser downloads these resources one after the other in separate TCP channels. The number of the TCP channels the server or for that matter the client can handle is finite, therefore the browsers limit themselves not to open more than four TCP channels. It means that while four content elements for the page is downloading the other elements wait in a queue to be downloaded. If we have some very slow downloading content it may choke the download of the whole web page. You can run experiments with that writing some simple servlet that sends a complex HTML page to the browser and then you let some of the content elements download slow and others fast. Doing it in debug mode using Chrome you will get a nice Gantt chart of the download timings.

The network is also wasted creating a new TCP channel for each new HTTP connection. Creating a TCP channel require an SYN package traveling from the client to the server, then an SYN-ACK from the server to the client and then an ACK from the client to the server again before we can start sending data. In addition to these, the TCP protocol limits itself not to flood a lossy channel with a lot of data that is going to be lost anyway, so it starts slow, sending only a few data packages at the start and increases the speed only when it sees that packages are arriving in good shape and content. Let’s just think about that three-way handshake that starts the TCP channel. The network between the client and the server has a certain lag and has a certain bandwidth. The lag is the time needed for a package to travel from the client to the server or the other way around. The bandwidth is the number of bits that can be pushed through the network between the client and the server during a given time (like one second). Imagine a hose that you use to fill buckets. If it is long it may take two or three seconds until the water starts to pour after you opened the tap. If it is narrow filling a bucket can take a minute. In that case, 2-3 seconds at the start is not a big deal, you have to wait a minute anyway. On the other hand, if the hose is wide the water may run in amount filling the bucket in ten seconds. Three seconds delay is 30%. It is significant. Similarly the TCP channel slow-start lag is significant in fast networks, where the bandwidth is abundant. Fortunately, we go in this direction. We get fibers in our homes replacing the 19.2kbps dial-up modems. However, at the same time, HTTP/1.1 lag is an increasing problem.

There is a header field Keep-alive that can tell the server not to close the TCP channel, but rather reuse it for the next HTTP request and this patch on the scar of HTTP/1.1 helps a lot, but not enough. The blocking slow resource problem is still there. There are other problems with HTT/1.1 that HTTP/2 addresses but this, using many TCP channels to download several content pieces to the client from the same server is the main issue related to server push, which is indeed the topic of this article.

HTTP/2

HTTP/2 uses a single TCP channel between the server and the client. When the content is downloaded from different servers the client will eventually open separate TCP channels to each server, but for the content pieces that come from the same server, HTTP/2 uses only one TCP channel. Using multiple TCP channels between a certain client and a single server does not speed up the communication, it was only a workaround in HTTP/1.1 to partially mitigate the choking effect of slow resources.

A request and a corresponding response do not use exclusively the TCP channel in HTTP/2. There are frames and the request and the response travels in these frames. If a content piece is created slowly and does not use the channel for some time then other resources can get frames and can travel in the same TCP channel. This is a significant boost of download speed in many cases. The change is also transparent for the browser programs being either JavaScript or WebAssembly. In the case of WebAssembly, the change is extremely simple: WebAssembly does not directly handle XMLHttpRequest, it uses JavaScript implemented and imported functions. In the case of JavaScript, the browser hides the transport complexity. JavaScript network API is just the same as it was before. You request a resource, you get one and you do not need to care if that was traveling in its exclusive TCP channel, mixed into HTTP/2 frames or was sent to you by pigeon post. On the server side, the approach is the same. In case of Java, a servlet application gets a request and creates a response. It is up to the container, the web server and to the client browser how they make it travel through the net.

The only difference, where server application may change is server push. This is a new feature and the new API gives an extra possibility for a server application to initiate a content push to the client.

When to Push, What to Push?

The server push typically can be used in a situation when the application prepares some content slowly and the application knows that this is going to be slow and it also knows that there are other resources, typically many small icon images that can be downloaded fast and will be needed by the client. Thus the conditions for the server push are (PRECONDITIONS)

- the content requested is slow,

- the application knows it is going to be slow,

- there are other resources that will be needed by the client after this resource was downloaded,

- the application knows what these resources are,

- these resources can be downloaded fast.

In this case, the servlet can initiate one or more push that may deliver the content to the browser while the main content is prepared. When the main content is ready, and the client browser realizes that it needs the extra resources they are already there. If we do not push the resources they will be downloaded only after the original resource was processed when the browser realizes that the extra resources are needed. In a simple example, when the browser sees all the img tags and knows that it needs the icon images to render the page. This is what the above animation tries to show in a simple way.

How to push

To initiate a push it is more than simple. The servlet standard 4.0 extends the HttpServletRequest to create a new PushBuilder whenever the servlet calls req.newPushBuilder() on the request object req. The push builder can be used to create a push and then invoking the method push() on it will initiate the sending towards the client. It is as simple as that. The only parameter that you have to set is the path of the resource to be pushed.

var builder = req.newPushBuilder(); ... builder.path(s).push();

Sample application

The sample application to test server push is a servlet that responds with an HTML page that contains one hundred image references in a 10×10 table. Essentially these are small icons from the http://www.flaticon.com website

The first thing the servlet does is to initiate the icon downloads via server push. To do that it creates one push builder and this single object is used to initiate 100 pushes. After that, the servlet goes to sleep. This sleep simulates the slow inner working of the servlet response. A real application in this time would gather the information needed to send the response from the different database, from other services and so on. During this time the server and the client have enough time to download the PNG files. When the response arrives the files are there and the images are displayed instantaneously. At least that is what we expect.

The servlet has a parameter, named push that can be 1 or 0. If this parameter is 1 the servlet pushes the PNG files to the client, it is 0 then it is not. This way we can easily compare the speed of the two different behaviors.

public void doGet(HttpServletRequest req, HttpServletResponse resp) throws IOException {

final String titleText;

var builder = req.newPushBuilder();

var etag = now();

if (builder == null) {

titleText = "Good old HTTP/1.1 download";

} else {

var pushRequested = parse(req).get("push", 1) == 1;

if (pushRequested) {

titleText = "HTTP/2 Push";

sendPush(req, builder, etag);

} else {

titleText = "HTTP/2 without push";

}

}

var lag = parse(req).get("lag", 5000);

var delay = parse(req).get("delay", 0);

var sleep = new ThrottleTool.Sleeper();

sleep.till(lag);

resp.setContentType("text/html");

sendHtml(req, resp, titleText, etag, delay, sleep);

}

The servlet can also be parametrized with query parameters lag and delay.

lag is the number of milliseconds the servlet sleeps counting from the start of the servlet before it starts to send the HTML page to the client. The default value is 5000, which means that the HTML sending will start 5seconds after the servlet started.

delay is the number of milliseconds the servlet sleeps between each image tags. The default value is zero, that means the servlet sends the HTML as fast as it can send.

For the push, it is interesting how we get the builder object. The line

var builder = req.newPushBuilder();

returns a new builder object that can also be null. It is null if the environment does not allow push. The simplest case is when the servlet is queried through normal HTTP and not HTTPS. HTTP/2 works only over TLS secure channel and that way if we open the servlet via HTTP it will not be able to push anything.

After this, the method sendPush() sends the push contents as the name implies. Here is the method:

private void sendPush(HttpServletRequest req, PushBuilder builder, long etag) {

for (var i = 0; i < 10; i++) {

for (var j = 0; j < 10; j++) {

var s = imagePath(i, j, req, etag);

builder.path(s);

builder.push();

}

}

}

The method imagePath() calculates the relative URL for the png based on the indices and this path is specified through the push builder. The builder is finally asked to push the content. This call to push() initiates the push on the server.

The builder is used literally one hundred times in this example. We do not need new builder objects for each push. We can safely reuse the same objects. The only requirement is that we set all the parameters before the next push we need. This is usually only the path.

Image Server

The icon images are not directly served by the server in the demo application. The URL for the icon resources is mapped to a servlet that reads the icon PNG from the disk and writes it to the response. The reason for it is twofold. The chronologically first reason is that during the application debugging I needed information when and how the resource is collected and in case the resource is just a plain file that the server directly handles I do not have many possibilities to debug or log anything. The second reason is that the demo needs network throttling. Just as in case of the main HTML resource that waits 5 seconds before it vomits out the HTML text images also need to slow down to show a good demonstration effect. There is a throttling functionality in the debug mode of the browsers. However, it seems that this throttling in Chrome is architecturally between the cache where the pushed resources are temporarily stored and the DOM displaying engine. Implementing throttling on the demo server in our code is certainly at a good place from the experiment point of view and it can not happen that the already pushed and downloaded resource is loading throttled into the screen.

For this reason, the image servlet has two query parameters. imglag is the number of milliseconds the servlet waits after a hit arrives and before it starts to do anything. The default value in case the parameter is missing is 300 milliseconds. The other parameter is imgdelay that specifies the number of milliseconds the server consumes sending the bytes of the image to the client. This is implemented in a way that the server sends each byte individually one after the other and in case the current time is proportionally too soon to serve the next byte then the server sleeps a bit. The default value is 1000, which means that each icon is delivered from the server in approximately 1.3sec. The code itself is not too educational from the server push point of view. You can see it in the GitHub repository https://github.com/verhas/pushbuilder/blob/master/src/main/java/javax0/pushbuilder/demo/ImageServer.java

PushBuilder methods

The PushBuilder class has many other methods in case you need to build a request that has some special characteristics. When you initiate the push of a resource you actually define an HTTP request, for which the resource would be the answer. The actual resource is provided by the server. If it is a normal static resource, like an image then the server will pick it up from the file system. If it is some dynamically calculated resource, then the server will start the servlet that is targeted by the request. What the push builder really builds up is a request that stays and is used on the server and the client will actually never issue this request after the resource was already pushed. The setter methods of the class set request attribute, like parameters, headers etc.

method()

You can set the method of the request that the resource is a response to. By default, this is GET and this should be OK most of the time. If the resource is a response to a

POST, PUT, DELETE, CONNECT, OPTIONS or TRACErequest then we can not push the resource anyway because the HTTP/2 standard does not allow resources of those kinds to be pushed. What remains is the HEAD method that does not seem to be meaningful. I believe that the method method() is in the interface

- for compatibility reason if ever there will be some new method,

- for the sake of some application that uses some proprietary non-standard method

- or as a joke (a method called method).

sessionId()

This method can be used to set the session id that is usually carried in the JSESSIONID cookie or in a request parameter.

set, add and remove + Header()

You can modify the header of the request using these methods. When you invoke setHeader() the previous value is supposed to be replaced. The addHeader() adds a new header. When you reuse the same object adding the same header again and again may result the same header in the request multiple times. Finally the removeHeader() removes a header.

Note that some tutorials also add the header Content-type and the value in some of the tutorials is image/png. This is erroneous even though it does not do any harm. The headers we set on the push builder are used to request the resource. In our example, the images are not directly accessed by Tomcat, but rather are delivered through a servlet. This servlet reads the content of the PNG file from the disk and sends it to the writer that it acquires from the response object. This servlet will see the headers set in the push builder. If we set the content type to be image/png, it may think that we do are a special kind of stupid sending an HTTP GET request body that is PNG format. Usually, it does not matter, servlets and servers tend to ignore the content type for GET request especially when the content has zero bytes. What format does a non-existent picture have?

get methods

What you can set on the push builder object you can also get out. You can use these getHeader(), getMethod(), getHeaderNames(), getPath() and so on methods to see what the current value of the values is in the push builder.

Experiments

During the experiments, I could not see any difference between HTTP/2 with and without the push. The download using HTTP/2 was inevitably faster than HTTP/1.1, but there was no difference between the push and the non-push version. I used Chrome Version 67.0.3396.99 (Official Build) (64-bit). The browser supports the push functionality but the developer tools do not support the debugging of the push. Pushed contents are displayed as normally downloaded contents. There is some secret internal URL (well, not really a secret since it is published on the net), that will show the actual frames, but it is not too handy. What I could see there finally, that the push itself worked. The images were pushed to the browser while the main HTML page serving servlet was having its 5 seconds sleep, but after that, the browser was just downloading the images again, even if I switched on browser caching.

Since HTTP/2 was started by SPDY protocol and it was pushed by Google (pun indented (again)) I strongly believed that it is my code that does something wrong. Finally, I gave up and fired up a Firefox and here you go, this is what you can see on the screen captures:

Summary Takeaway

Server push is an interesting topic and a powerful technology. There are a lot of preconditions to use it (see listed above, search for “PRECONDITIONS”). If these are all met then you can think about implementing it, but you should do experiments with the different network setups, delays and with the different client implementations. If the client implementation is less than optimal then you may end up with a slower download with a push than without one. There is a lot of room for development in the clients. Some of these developments will just mature the way the browsers handle server pushed resource, but I am almost sure that soon we will also have JavaScript API that may register call-back functions to be triggered when a push starts so that it will not only be the browser autonomously who can refuse a push stream but also the client-side JavaScript. Keep the eyes and your mind open for the development of HTTP/2.