Three Laws of Privacy: A Set of Rules to Build a Privacy Standard

Three Laws of Privacy: A Set of Rules to Build a Privacy Standard

Over the years has become clear that SciFi authors shape the future. No one can predict the future — not even experts, but SciFi authors get pretty close.

Science fiction has a big responsibility. It shapes the way people understand the most important developments of our time. So authors, screenwriters, and any writer who writes science fiction, have a big responsibility in the way they picture the future. Because if they picture it in the wrong way, people might focus on the wrong problems.

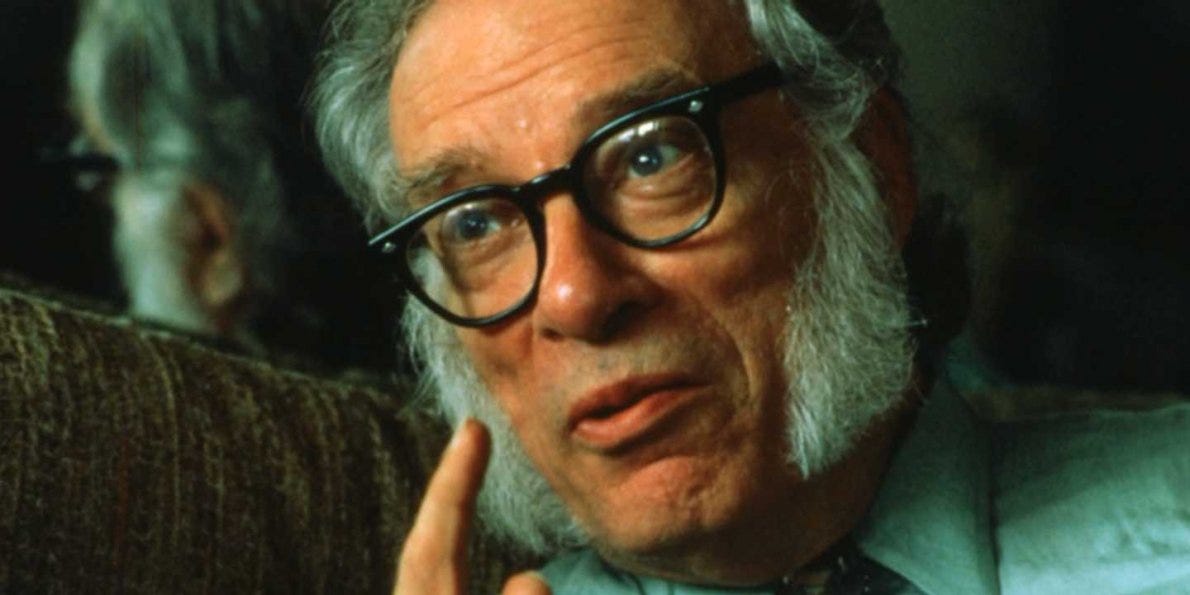

Back in the 1950s Asimov thought that something could go wrong with robots in the future. He understood he had the responsibility to deconstruct that problem, and come up with a solution to prevent robots from doing harm to humans. The solution? The Three Robotic Laws:

- A robot may not injure a human being or, through inaction, allow a human being to come to harm.

- A robot must obey the orders given it by human beings except where such orders would conflict with the First Law.

- A robot must protect its own existence as long as such protection does not conflict with the First or Second Laws.

Maybe we don’t recognize the value of Asimov’s work, but at some point this might help us build a better world. That’s what I want to do here. This is not an attempt to predict the future, but to build the foundation of a structure where our privacy can be secured and not turned against us.

The problem is seeing the problem

One of the biggest lessons I’ve learned with design, is that you can’t design anything properly until you see the problem.

Steve Jobs and his team — at the early stages of the iPhone — asked themselves: How a phone should look like? So, when they went to first principles, it became obvious that they had to get rid of the physical keyboard and have a touch screen. The problem was seeing the problem.

Or consider Howard Hughes when he reinvented modern airplanes. Most airplanes at the time had two wings on each side (one on top of each other). Then he asked himself: Why do airplanes have four wings instead of just two? That was the right question.

Solving problems is not the hard part. The hard part is figuring out the right question to ask and define the problem — the real problem.

Once you realize what the problem is, then coming up with the iPhone or removing two wings in an airplane isn’t actually that complicated.

The challenge is to leave all kinds of biases behind and go first principles. It’s about detaching yourself from it’s supposed to be this way, and go to how should it be? Once you do that, then you can start seeing the problem as it is.

When Asimov came up with the Three Laws of Robotics, even though we’re talking about science fiction, he had to go to first principles and ask himself: What are the main dangers we could ever face with robots? How could we prevent this from happening?

It turns out, with privacy we have to go through the same process. Understand exactly what’s the problem we’re facing, and come up with a solution. The solution doesn’t have to be a product or service, it can be a set of rules to set the structure of the building. It can be a manual that serves as reference.

With privacy we’re not actually seeing the real problem. So first, let’s identify it, and maybe we can come up with a solution.

How to ignite change

The problem we’re trying to solve here is disruptive. This is a revolution. Maybe we don’t see it that way, but it is. The same has happened for centuries, when there’s a revolution going on nobody notices it until it explodes. And it’s only in hindsight when it’s easy to spot the moment when it ignited.

Well, the private revolution has started.

And what revolutions do is destroy the perfect and enable the impossible.

Perfect as the system corporations and governments gave us to play in. And impossible as what people didn’t think was theirs in the first place (privacy and data).

We’re living on a thoughtful, well designed system that has sucked us in. So before we arrive to the conclusion of what the actual problem is, we need to decode that system in order to understand how to hack it.

In the end, systems are based on the status quo. That’s why there’s widespread apathy towards privacy and data ownership. After all, following the system is hardwired into us, even if that means going against our own interests, we still defend the status quo.

Deconstructing the problem

What we’ve got to do here is try to understand the system, then point out the vulnerability that could allow us to hack it. And, maybe, we’ll be able to collapse the entire system.

I’ve been talking with a lot of people about this, and I found several interesting points:

- It’s a behavioral problem. People don’t understand the importance of privacy and how it affects them, or will affect. And for most of them, the pile of benefits of getting these “conveniences” is bigger than the pile of benefits of protecting their privacy.

- Lack of data ownership. People can’t control their data — somebody else owns it and uses it at their will.

- The value of data increases over time — and permission is just required once, if ever. Once it’s out there, it can’t be taken back, and people don’t know what they’re giving permission for.

- National solutions don’t work on a global scale. (More on this later.)

- The power of ruling the 21st Century is at stake.

These are the top characteristics that will get us to the problem at hand. So let’s group them properly and analyze the three main characteristics of the privacy problem:

1) It’s a behavioral problem.

The first problem we encounter is a behavioral one. This apathy and lack of understanding with privacy is the same one as the problem with open defecation in the developing world.

In 2007 the British Medical Journal asked its readers to vote on the most important medical achievements since 1840. The winner? The sanitary revolution — especially the securing of clean water.

There are over a billion people who don’t have access to clean water — they don’t even have toilets and have to defecate outdoors. This, of course, makes it easy to spread mass diseases, and most of this could be avoided by solving the open defecation problem. So how could you end this practice?

Several years ago WaterAid funded the constructions of toilets in Bangladesh, but people didn’t use them and continued to defecate outdoors. In order to figure out why people weren’t using them, they sent Dr. Kamal Kar to evaluate the work.

The problem wasn’t the construction, it was a behavioral one. It turns out that when you give someone who lives on a dollar a day a $300 toilet, they won’t dare to use it. Umelu Chiluzi said: “If you ask them, why are you not using that latrine? They would tell you, ‘Are you sure I should put shit in that structure that is even better than my house?’”

Kar knew right away that this problem wasn’t going to go away until people wanted that change. It wasn’t a hardware problem after all. So he had to show people (not tell them) what they were eating.

Kar came up with a methodology called Community-Led Total Sanitation (CLTS), which is about going to those villages and ask questions, not to offer advice. The idea is to make people get to the conclusion by themselves.

I recommend you to watch this video, it explains the whole process. But this is how it works:

- They go to the village and ask “where do people shit?” (Kar uses the word shit, it definitely creates a bigger impact than defecate. If you want to create an emotional reaction, shit works.)

- They get to the shithole and the facilitator asks: “Whose shit is this?” “Did anyone shit here today?”

- Then they create a subtle link with the flies: “Are there often flies here?” Everybody nods.

- By this point the whole village is around. They go to another place (nobody can handle the smell) and the facilitator asks to draw a map of the village. And then draw with yellow chalk the places where people shit. Now the whole map is yellow — it surrounds people’s homes.

- The facilitator asks for a glass of water and ask around if people would drink it. Everybody says yes. Now he pulls a hair from his head, dunk it in the shit and put it in the glass. Suddenly nobody would want to drink the glass of water.

- Here’s where he creates the big connection. He makes them arrive to the conclusion that flies have legs, and those legs carry each other’s shit. And since those flies are often on the food too, they’re all eating each other’s shit. Now they, desperately, want a solution.

This wasn’t a hardware innovation. It was a simple communication process where people saw the real truth, and it disgusted them. When that happens there’s no way out. They didn’t really see the truth until they saw it in the most purest and brutal way.

Once you see it you can’t unsee it.

We’ve got to go through the same process with privacy. We’ve got to show people the real truth and how disgusting it is.

First problem, then, is a behavioral one. We need a system as brutal and effective as the CLTS, in order to change people’s behavior. Awareness is critical.

2) People give away the most precious resource of the 21st Century: Data.

One of the most fascinating things about history is the ability it gives you to understand the patterns that ignited change. You just have to look back for a few hundred years in order to understand some of the changes we’re living now.

Giving away your most precious resource for cheap is something that’s happened for hundreds of years. But it’s only looking backwards when we get to understand how valuable something was — because at the moment for the ones who lost it all, wasn’t clear at all. There’s a similar pattern between the way we treat our privacy and data, and how European imperialists took over America.

In 21 Lessons for the 21st Century, Yuval Noah Harari explains it:

“Even if you don’t know how to cash in on the data today, it is worth having it because it might hold the key to controlling and shaping life in the future. I don’t know for certain that the data-giants explicitly think about it in such terms, but their actions indicate that they value the accumulation of data more than mere dollars and cents.

“Ordinary humans will find it very difficult to resist this process. At present, people are happy to give away their most valuable asset — their personal data — in exchange for free email services and funny cat videos. It is a bit like African and Native American tribes who unwittingly sold entire countries to European imperialists in exchange for colourful beads and cheap trinkets. If, later on, ordinary people decide to try and block the flow of data, they might find it increasingly difficult, especially as they might come to rely on the network for all their decisions, and even for their healthcare and physical survival.”

We’re in big trouble.

Once people are aware of how vulnerable they are when they give away their privacy and data, it’ll be time to give them tools to actually control it. Today we’re not even close to have a solution. Even if lots of people praise blockchain as the ultimate solution, it still doesn’t solve it.

It’s doesn’t matter if Facebook says they want you to control your data. That’s an illusion. They offer more privacy options because that makes people share more stuff with them. Real control, though, comes from deciding who can access it, how they might use it and what for. Until you have that kind of control, they problem isn’t solved.

Picture this: you have a property — a beautiful house in the country. On a Sunday morning you’re reading on your living room and someone gets in. Sneaks around. Opens your fridge. Looks for clues to figure out what you’ve been doing, and anything you can imagine. Would you be comfortable with that? I bet you wouldn’t.

The thing is, you wouldn’t even know when someone gets into your home. You’d be there doing your thing, and other people would have the power to come in and out without you even notice it.

If you think about it, we’ve got more than 100 years of experience dealing with physical property, but we’ve got none when it comes to digital property. But the stakes are the same — and I’d say it’s way more scary not to own your digital property.

Let’s say we don’t come up with a system to control data as personal property, but we do come up with the right regulations. (That’s kind of what we’re trying in Europe with the GDPR.)

One of the things we can do is to apply political pressure to make sure tech giants and other organizations don’t do anything weird with our data. So far so good.

But, if the incentives are good enough, they still have the power to make use of it, and make sure they don’t get caught. At any time, the FBI can go to any American company and extract data on anything or anyone. Corporations and governments could still access your data, and violate your privacy.

That’s not all, of course. The other danger I’ve already pointed out is that the value of data increases over time. Nobody knows how valuable your data will be in 2035. But since it gets more valuable, you better keep it safe and not give it away.

3) It’s a global problem, not a national one.

Consider climate change. Do you think this is a problem you can solve on a national scale?

The Kyoto Protocol was useful because lots of countries adopted it. However, in the moment China refused to join the protocol, everything was doomed. What can you do when some countries don’t agree or decide to leave?

Climate change isn’t something you solve with a few countries collaborating. It’s a global effort.

The same happens with privacy. While some people might not see the connection here, let me show you just a reason why this is a global problem that requires a global solution:

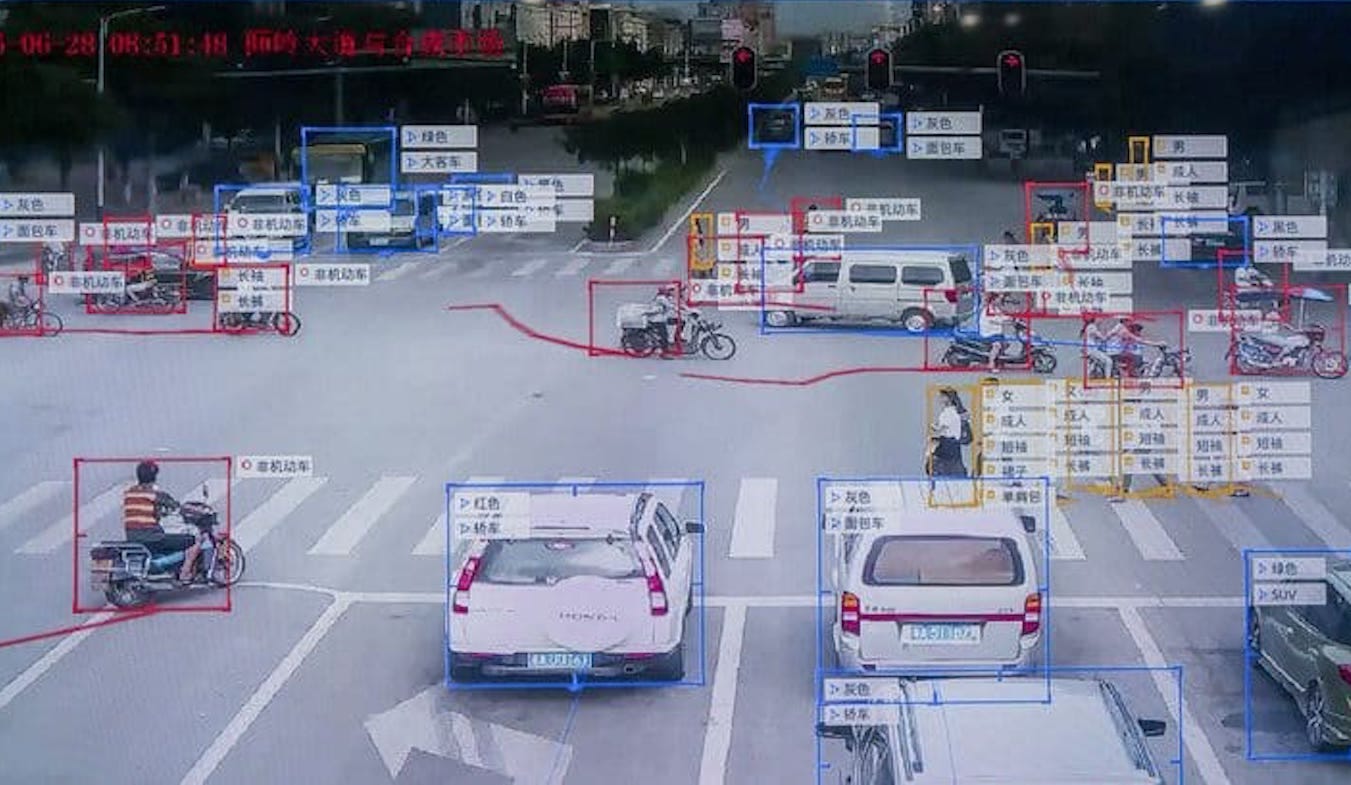

a) Tech companies have access and influence over all over the world, but it’s more centralized than ever before.

b) There’s an AI race. Power is at stake. As Harari says in his latest book, data is what will determine who rules the 21st Century.

There are a few more things to consider on regulations and politics, though.

Yuval Noah Harari also says in his book that a country can’t develop in secrecy nuclear weapons. At some point people would notice it. However, any country can work on AI weapons in secret — and nobody would ever notice it.

Even if countries decide that technological disruption is a threat for humanity and decide to regulate it… Even if the USA agrees with China that both of them won’t work on AI, how can you know that they won’t actually develop AI? That’s the tricky part.

At some point, every country would end up developing AI so they’re not left behind. Every country would end up doing the same.

What fuels AI is data. So if a country wants to keep up with China, they’d have to copy their practices in surveillance, so they can gather as much “fuel” for the development of AI.

Should we trust in the good faith of governments, corporations and organizations, when they don’t even trust themselves?

This change has to happen on the streets. Maybe Europe can work something out, but this is a global problem and we need to tackle it globally.

So, what’s the problem?

There isn’t a single problem. There’s a sequence of problems — but what matters here is their order.

I’m going out on a limb here: I strongly believe this is an awareness problem.

Yes, ownership and regulations are big problems too, but they are not the actual root.

But what’s a root problem, anyway? The cause of a problem, but also as the way you can collapse the entire system. Because if you remove the root, they can’t feed the system anymore.

If people are truly aware of how their lack of privacy is affecting their lives, then the system has to collapse. It has to.

With the natives example from a few paragraphs back, do you think the problem was that they didn’t have regulations or something, or was it that they didn’t understand the devils deal?

Or consider the CLTS example from point #1. They did have the tools (toilet), and lots of organizations were trying to convince people there to use the toilets, but again, people who don’t think they have a problem don’t seek for a solution.

I strongly believe this is the same thing for privacy. We can have the tools (something that gives you ownership over your data), and even have regulations, but if people are not aware of why they shouldn’t give up on their privacy, nothing else matters.

Three Laws of Privacy

Now we’ve got our root problem: awareness. So it’s time to lay out the foundation of a privacy standard that tackles the real issue, and then work it out to solve the whole sequence.

The next three laws will be the shoulders which our privacy can rest upon:

- A Corporation, Organization or Government may not invade the privacy of a human being. It may only happen with explicit permission, requiring full transparency of the purpose behind the data extraction. The individual has to understand the real use of his or her data.

- A Corporation, Organization or Government must give up the ownership of that data. It is the individual who owns it. It can’t be stored nor used in the future. It may only be used in the future for other purposes, except where such usage would conflict with the First Law.

- A Corporation, Organization or Government may have permission to invade an individual’s privacy and make use of his or her data, as long as such permission does not conflict with the First or Second Laws.

Building a privacy standard

Maybe this article raises more questions than solutions, but we’ll have to discover the solutions along the way. We don’t know what we don’t know. It’s only through experience where we can put this into practice and learn. That said, before we start having real experience, we need a structure to build our buildings upon. These three laws of privacy are that.

I don’t know how exactly we’re going to apply them. But without these fundamentals, I believe we’re going to screw it up. Maybe we’d need to revisit these laws as we get more knowledge and experience on the issue, but at least it’s a start. And that’s what we need, to start.

We need to change the conversation and bring the problem to the table. As they say, you can’t appreciate the solution until you appreciate the problem.

You might have noticed that I didn’t include politics in the three laws. It’s not because they’re not important, but because there’s no short-term solution for this.

We can’t rely on political pressure — not yet anyway. It’s not that politicians have bad intentions. I believe most people mean well (even politicians), but however good their intentions are, by the time we come up with some regulations it’ll be too late. And it goes without saying that we can’t solve this in a four-year window. Technology grows faster and faster every day — exponentially. And engineers at Silicon Valley won’t wait for politicians to approve anything. They think in terms move fast and break things. Even if that means breaking us.

I believe this change has to happen on the streets. We’re on our own here, whether we want it or not. We are responsible of what we make with our future. People have to be aware of the problem. Then, and only then, we can apply political pressure — otherwise the debate won’t even be on the table.

Let’s do this right. Spread the word. Try to get people to watch out for their privacy. Share this article, or write one yourself, but spread the word.

If not us, who? If not now, when?