The Tyranny of the Perfect Life

The Tyranny of the Perfect Life

At age twenty-two, I spent two weeks drafting a list of all the things I wanted to accomplish before I turned thirty.

I called it my Eight-Year Plan. At the time I was lonely, socially awkward, and dissatisfied, and the list was meant to be a cure for my problems. It was a blueprint, a rubric, a recipe that contained all the necessary ingredients of the “perfect life.”

I’ve since misplaced that list. This is probably a good thing — half of it was too embarrassing to share here, and the rest was a boring collection of secondhand dreams:

- Start a successful company

- Develop superhuman social skills (aka be really good with women)

- Earn a million dollars

- Travel the world

The list, at the time, felt cool and unique. But in retrospect, I was doing what every second-rate guru and life coach recommends: (a) imagine your ideal future and (b) create a plan to get you there.

I didn’t know it then, but I was also subjecting myself to the tyranny of the perfect life.

The Perfect Day

In the tyranny of the perfect day, blogger and author Matthew Sweet writes of his attempts to make each day conform to his ideal of the perfect:

“A while ago I discovered my ‘perfect morning’. I liked to rise before the sun, meditate for a while, read whilst drinking a few cups of coffee, then write for a few hours. After that, I’d squeeze in whatever else my relationships, commitments and ambitions demanded of me. So, I thought, why not try to make every morning like that? I tried and it was surprisingly successful. But it also made me fragile. If I didn’t get up early enough then I felt the morning was lost. If my meditation session went terribly then it threw me out of rhythm. If I couldn’t focus whilst reading I felt annoyed. If I sat at the keyboard and nothing came to me, I’d wind myself up into a hybrid state of anxiety and fear. I was seeking uniformity in my mornings and Life was giving me the middle finger, thwarting my quest in mostly consistent, but sometimes unexpected, ways.”

Sweet’s story contains a paradox and a lesson.

Life is always more out of our control than we would like it to be. The perfect day is like that distant relative that, once or twice a year, shows up with presents and stories of exciting overseas adventures — despite our wishes, she only visits us on occasion, at random times, and never stays for as long as we would like her to.

“Stay hungry,” some say, “and never settle.” But why spend 364 days a year failing and flailing in order to make one day a year conform to your ideal of the perfect?

Also, as the film Groundhog Day shows us, the perfect day only remains perfect as long as it only shows up once in a while. If every day was “perfect” it would quickly become just another part of our ordinary experience. Then, we would need a new fantasy to take its place.

So much for the perfect day. But what of the perfect life?

The Quest for Uniformity — At All Costs

Similar to Sweet’s pursuit of the perfect day, the pursuit of the perfect life can mean imposing an artificial, rigid, uniformity on your life that does more harm than good.

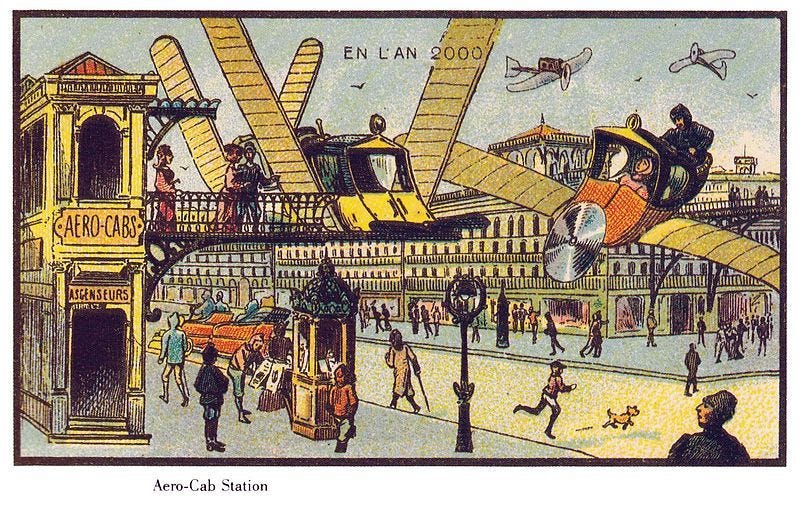

As the history of the 20th century has shown us, the pursuit of utopian dreams never takes us quite where we want to go. Plans backfire. People change. New technologies develop. Life and history stubbornly refuse to conform to our fantasies of control.

Hitler, Mao and Stalin are all obvious examples. To them, a few million deaths were nothing, a small price to pay in exchange for a perfect paradise-on-earth that would last always and forever. Only problem one: The perfect life never came.

But what are some less gruesome cases?

In his book Seeing Like a State: How Certain Schemes to Improve the Human Condition Have Failed the political scientist James Scott writes of various failed attempts to impose artificial, top-down structure onto the complexity of life.

One example is the failed language of Esperanto. What the designers of the language failed to understand, argues Scott, is that languages are about far more than just ordinary communication:

“…language per se is not for only one or two purposes. It is a general tool that can be bent to countless ends by virtue of its adaptability and flexibility. The very history of an inherited language helps to provide the range of associations and meanings that sustain its plasticity.”

Likewise, catastrophes of urban planning, despite good intentions, were caused by a similar flaw in thinking. What sounds good on paper may ignore many sides of what makes a city or a community valuable:

“In much the same way [as one creates a language,] one could plan a city from zero. But since no individual or committee could ever completely encompass the purposes and lifeways, both present and future, that animate its residents, it would necessarily be a thin and pale version of a complex city with its own history. … Only time and the work of millions of its residents can turn these thin cities into thick cities. The grave shortcoming of a planned city is that it not only fails to respect the autonomous purposes and subjectivity of those who live in it but also fails to allow sufficiently for the contingency of the interaction between its inhabitants and what that produces.”

Lifestyle design is a term I used to use a lot, but — like disastrous episodes of urban planning — my life hasn’t always responded to “design choices” in the way I expected.

A year after I wrote my Eight-Year Plan, I quit my job with the intention of traveling the world for at least a decade. I had absolutely no desire to settle down or find a stable life partner. That wasn’t what the cool kids did.

Of course, a few short years later, I did precisely the reverse: I quit traveling, settled down (in Japan, of all places), and got married.

Before I met my wife, my “ideal woman” was an intelligent, polymathic book-lover, cultured and with a PhD in math or science. Instead, my wife is a dance teacher, rarely reads, hates math, and never went to college. She’s great.

To pursue the perfect life is to assume that you have knowledge of who you are, what you want, and how you might get there. But history, science, and personal experience have all taught me that I’m not so good at knowing myself or what I want from life.

The things I thought I wanted a few years ago are different from the things I think I want now. And, no doubt, they will be different again in ten years.

In what way, I wonder, does envisioning the perfect life assist me at all?

Pregnant Nuns In Atlantis

So far, I’ve suggested several things — that pursuing the perfect life imposes an artificial rigidity; that personal projects can backfire and do great harm; and that, because our values constantly shift, the perfect life will never be quite as satisfying as we imagine.

But all of this was, actually, just a side point. My main point is to suggest that the very idea of the perfect life is incoherent.

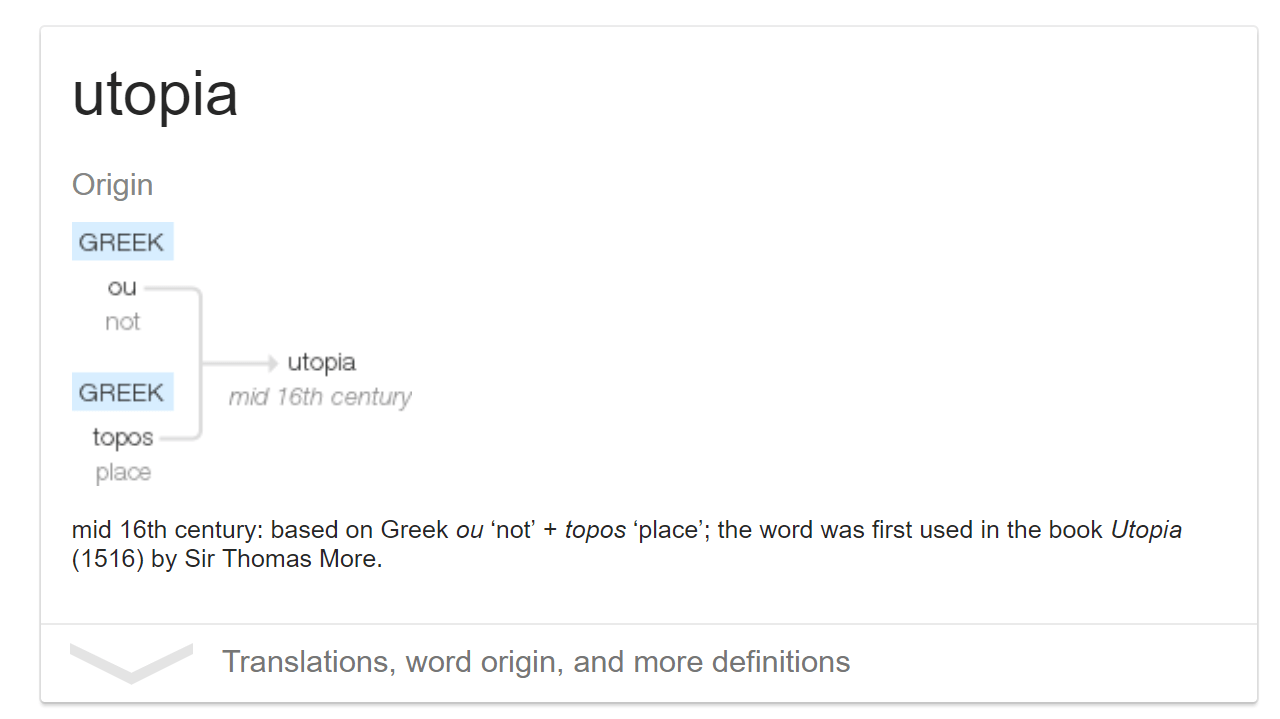

The word utopia, in its original form, meant “no place,” and no place is, I think, the only place where the perfect life can be found.

My inspiration here comes from Isaiah Berlin, the famed 20th century philosopher and historian of ideas. Berlin was a proponent of something called value pluralism.

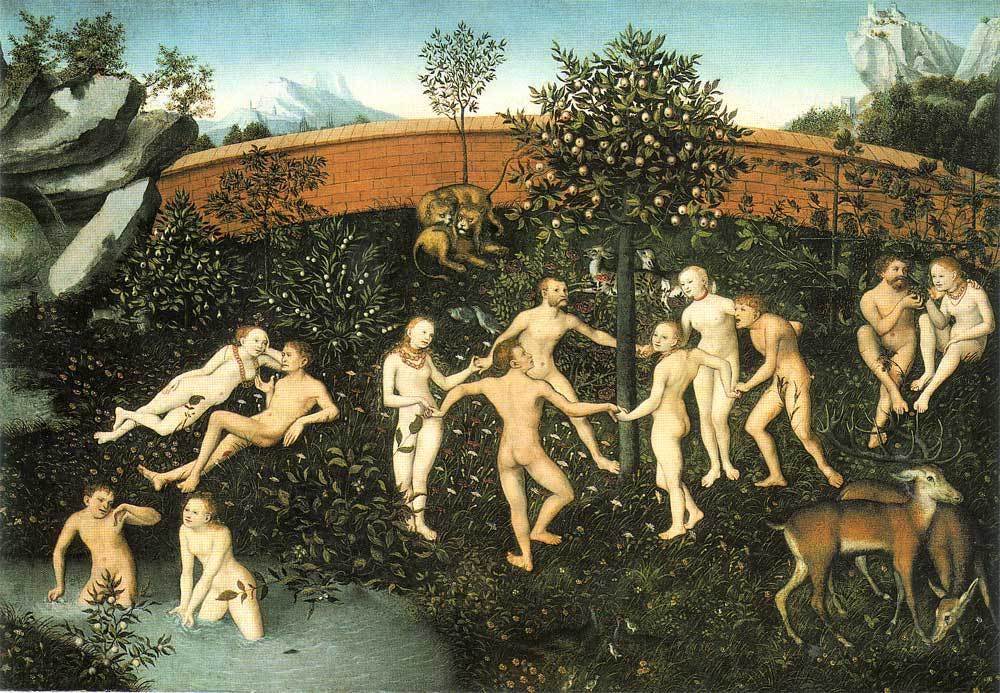

Humans have many needs and values. It is a hidden article of faith in Western thought — so widely believed that many of us never question it — that human needs and values can come together in perfect harmony.

There may be problems now, we say, but with the right political system, the right kind of education, the right economy, and the right technologies we can solve these problems once and forever.

But Berlin presents another possibility: What if our values and needs contradict one another, so that a gain somewhere means a loss somewhere else?

“Should democracy in a given situation be promoted at the expense of individual freedom? or equality at the expense of artistic achievement; or mercy at the expense of justice; or spontaneity at the expense of efficiency; or happiness, loyalty, innocence at the expense of knowledge and truth? The simple point I am concerned to make is that where ultimate values are irreconcilable, clear-cut solutions cannot, in principle, be found.”

You can’t be both pregnant and a nun — choosing one way of life means giving up many others.

My desire for health and long life is at odds with my desire to eat delicious, fatty foods from the local Lawson convenience store. My desire for privacy is at odds with the convenience of tools like Google and Facebook. My need for solitude is at conflict with my need for friends, belonging, and social approval.

In his book on Isaiah Berlin (an excellent introduction if you’re looking for one), the philosopher John Gray writes:

“Within any complex culture, there will typically be a diversity of forms of life, each with its associated virtues and excellences, available to many people, but it will not be possible to combine these forms of life within the compass of a single biography. This may be because the virtues of a nun, say, constitutively exclude those of a lover, or it may be because, though different virtues can be combined in a single person, they tend to crowd one another out, or to be conjointly realizable only at the cost of each being achieved at a low level. … [Certain forms of social flourishing emerge from] social structures, or entire cultural traditions, that are themselves constitutively uncombinable. … [Or they may] demand in the individual agent virtues or excellences that cannot, as a matter of moral psychology or philosophical anthropology, be realized together.”

When I traveled and lived out of my backpack, freelancing a few hours a week to fund my travels, I didn’t need to depend or rely on anyone. Some people dream of this kind of life, but it’s not all sunny weather and coconuts.

Long-term travel was bitterly lonely at times. Friendships never seemed to last, and I at times found myself culturally isolated.

Now that I’m married and live in one place, the loneliness has faded (for now), and I feel like I have a place where I belong. But these wonderful things also come with accompanying shadows. Family and community also mean responsibility. My failures don’t just hurt me; they also hurt my family and the people I work with.

To re-emphasize, the key thing to realize is that the very idea of perfection is incoherent. It’s not that you haven’t found the right vocation, right life partner, right morning ritual, or right dietary supplement that will “tip the scales” towards a life of perfect harmony.

Rather, the human animal is so full of contradicting needs and desires that the idea of a perfect, problem-free life is something that can only exists in imagination — or, in my case, always somewhere five-to-eight years in the future.

No Final Solution

When I was most-obsessed with my Eight-Year Plan, I was tyrannical, self-hating, and not so fun to be around. Friends and girlfriends were to be “liquidated” if not useful for personal growth. Time not spent productively was a failure of willpower or planning. I rarely took any days off and — when I did — I did it because taking time off would help me come back later and work harder.

I tried to compress all sides myself to a single, sharp and focused point. But over-focusing also means tunnel-vision, and tunnel-vision means that much of the picture gets left out.

“Why,” a girlfriend once asked me, “do you never stop and look up at the sky?”

I end with a final quote from Isaiah Berlin. In Conversations with Isaiah Berlin, Berlin comments on a talk he gave in 1988:

“My talk … was intended to argue that the pursuit of a single, final, universal solution to human problems was a mirage. There are many ideals worth pursuing, some of them are incompatible with one another, but the idea of an all-embracing solution to all human problems which, if there is too much resistance to it, might need force to secure it, only tends to lead to bloodshed and the increase of human misery. … I believe that there is nothing more destructive of human lives than fanatical conviction about the perfect life*, allied to political or military power. Our century affords terrible evidence of this truth. I believe in working for a minimally decent society.”

Though Berlin speaks in a political context, I think this applies just as well to your life or mine.

The perfect life is always just around the corner but, if you stop for long enough and breathe, you may find that the minimally-decent life is here already, just under your feet.