How Much Is a Species Worth?

Estimates put the global cost of preserving endangered species and their habitats at $76 billion per year. The US government spends $7 billion per year on the cause, but countries with more biodiversity tend to have less to spend — Brazil is home to 13% of all life on Earth, but its conservation budget is just $180M.

There’s a lot of work to be done, and not enough money to do it. That’s not to say that we should be doing all we can, because it’s unclear whether conservation trumps the countless other issues competing for our resources. What’s important is to make sure the money that we do spend has an impact.

How do we decide which animals to protect?

In 1991, out of the 550+ endangered species in the United States, which do you think received the most conservation funding from the U.S. government?

The bald eagle. Of course.

“Charismatic megafauna” — pandas, giraffes, etc — receive more than the lion’s share of conservation funding, to the detriment of more unsightly but equally threatened species. You won’t be seeing a “Save the Eels” campaign anytime soon. It’s hard for us to think rationally about this stuff. We tend to prioritize animals we have a positive association with, often one rooted in childhood. (Have you ever seen a stuffed animal of an eel?)

Putting our feelings aside, shouldn’t we concern ourselves with species that are clearly valuable to us — the yellowfin tuna for meat, the Holstein cow for milk, the honey bee for pollination? What do we gain by trying to save the giant panda?

“Species” is a man-made category, one whose definition has no scientific consensus.

At first glance, it feels like stopping the extinction of species is linked to the idea of trying to preserve life, which most would intuitively consider valuable, if not a moral imperative. But the issue with moralizing is that “species” is a man-made category, one whose definition has no scientific consensus. Prioritizing the life of one species over another on the basis of this arbitrary category can easily lead to decisions that seem morally counterintuitive.

The more compelling argument in favor of preserving biodiversity? We know so little about the environment that the best strategy is to make sure we don’t mess anything up.

Less than 50 years ago, for example, we discovered Prochlorococcus, an ocean-dwelling bacteria to whom we owe 20 percent of the oxygen we breathe. There are likely countless undiscovered species that are essential to our lives. Choosing to preserve only those that provide a measurable economic benefit could risk the survival of others. And even when it comes to species we know, we’re still unaware of the delicate equilibria that we can upset — even with the noblest of intentions.

Another example: In the 90s, Indian farmers began treating their livestock with a new drug. This drug had knock-on effects that wiped out the local vulture population, providing an opening for feral dogs and rats to flourish. The resulting disease killed tens of thousands of people.

Undervaluing biodiversity could easily have unpredictable 2nd- and 3rd-order effects that cost us dearly, both in terms of economic capital and human life. How, then, do we correctly value a species?

The Economics of Conservation

Many conservationists have taken the (easy) stance of declaring that all species have intrinsic value. This isn’t terribly helpful when it comes to prioritizing scarce resources. Though it may feel uncomfortable, or even sacrilegious, to put a dollar value on an entire species, it’s important to think about conservation rationally if we want to achieve its goal.

There are two components to the value of species: “use value” and “non-use value.” Use value is the tangible utility we get from consumption — meat from an animal or wood from trees — whereas non-use value is everything else, including the value we get from just knowing that a species exists.

Many conservationists have taken the (easy) stance of declaring that all species have intrinsic value. This isn’t terribly helpful when it comes to prioritizing scarce resources.

Quantifying the use value of a species or ecosystem is relatively straightforward. We can easily measure, for example, the economic value of converting 100km² of the Amazon into farmland. Similarly, the fact that pharmaceutical companies are willing to pay $14,000 for a quart of blood from horseshoe crabs says something about that species’ value.

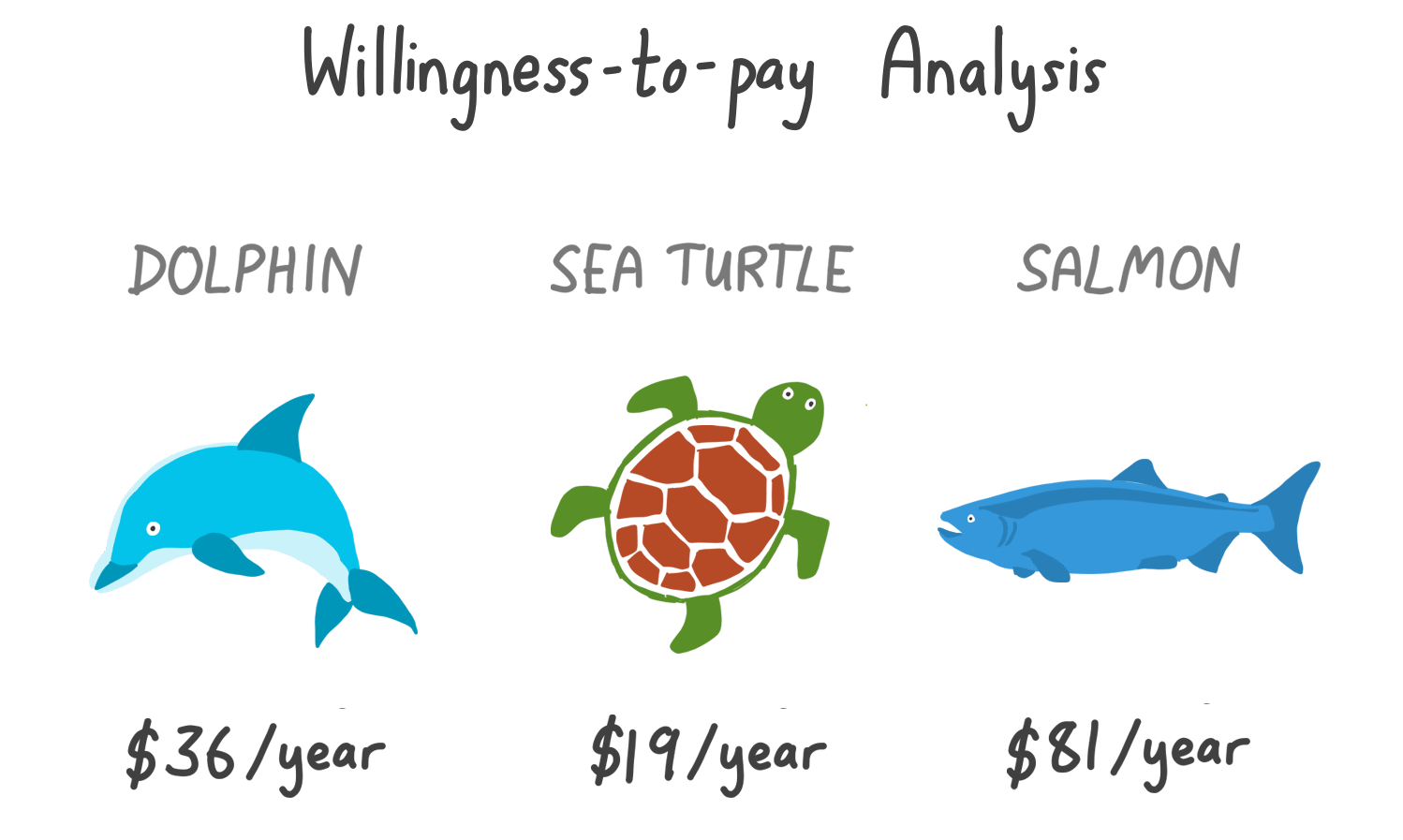

Non-use value is much harder to pin down. There’s no market for “the knowledge that rhinos exist,” and no revealed preferences from which we can infer the value of a rhino’s existence. All we can do in this case is rely on people’s stated preferences (i.e., how much they say rhinos are worth to them). This is extremely nebulous, especially because our stated preferences don’t often match our actual ones.

You’re probably glad that rhinos exist — at the very least, they look cool. How much is that worth to you? Even if you settle on a number — say, $10/year — there are countless species you’d think are equally deserving. Yet you’d probably agree that endangered species, as a whole, don’t actually give you hundreds of dollars of perceived value every year.

While it’s extremely difficult to quantify what most of us get out of wildlife, there are some who are willing to put a dollar value on the line: trophy hunters.

Dead or Alive?

Trophy hunting is the practice of hunting and killing large, sometimes endangered, animals for recreation. This shouldn’t be confused with poaching, an organized criminal practice that fuels the illegal wildlife trade.

Many of us would feel some discomfort or even disgust at the idea of hunting wild animals for sport. American dentist Walter Palmer received an onslaught of online abuse, even death threats, for hunting Cecil the Lion in 2015. That same year, Corey Knowlton of the Dallas Safari Club faced similar responses after hunting an endangered black rhino in Namibia.

What the media headlines often gloss over, though, is the fact that trophy hunting is effectively managed by conservation groups and provides a large source of their revenue. Hunters pay extraordinary sums to hunt certain species — Corey Knowlton paid $350,000 to hunt a single black rhino. South Africa is one of the continent’s biggest conservation success stories and relies on hunters like Corey — just a handful of them every year — for 60% of its conservation funding.

Another caveat: Selling a hunting permit doesn’t make it open season on rhinos. Conservation groups sell permits to hunt specific animals, typically those that are no longer productive members of the ecosystem. Elderly black rhinos are infertile and aggressive, killing other members of the species and posing a threat to locals and their crops.

Despite the economic arguments in favor of trophy hunting, it continues to divide public opinion. While countries like Namibia and South Africa have implemented it to great success, Botswana has been internally battling the issue for the last few years.

Top-down interventions tend to overlook the human factors at play. Any sustainable long-term solution will require buy-in from everyone.

In 2014, Botswana banned hunting, citing a decline in species numbers in hunted areas and following pressure from animal rights groups. Local communities were vehemently opposed to the ban — they lost a significant source of income and their crops faced increased threats from wildlife. Following mounting criticism, the new government are in the midst of a nationwide consultation process to consider lifting the ban.

The conflict between human well-being and conservation is difficult to resolve. Top-down interventions tend to overlook the human factors at play. Any sustainable long-term solution will require buy-in from everyone.

Trophy hunting is understandably controversial, but more innocent interventions aren’t much simpler. A recent proposal to build fences around conservation areas to stop humans and wildlife getting in each others’ way received significant pushback from those who believe wildlife should be allowed to roam freely.