Why Blockchain Needs Sci-Fi Right Now

Why Blockchain Needs Sci-Fi Right Now

Prophetic books, Joe Lubin’s favorite works, and how stories help us build.

“I want to write about people I love, and put them into a fictional world spun out of my own mind, not the world we actually have, because the world we actually have does not meet my standards.” –Philip K. Dick

Anticipating the Future

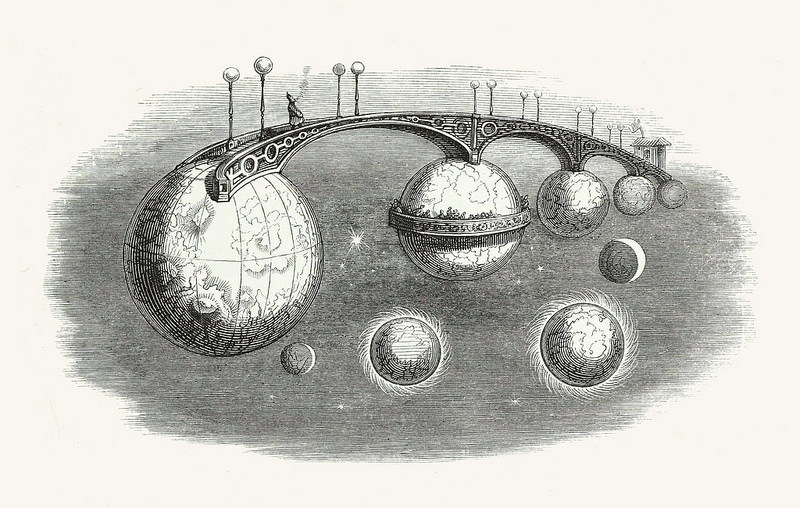

What do we talk about when we talk about science fiction? Science challenges us to imagine the world differently. Fiction invites us to imagine other selves in other lives — and, like science, challenges us to imagine the world differently, or other worlds entirely. Technology is in some sense a blend of the two, turning scientific concepts and innovations into tools that improve or enhance human lives. Those acts of imagination are a kind of anticipation, even a challenge.

Many ubiquitous technologies we use today were dreamed up by science fiction writers long before they could exist. Edward Bellamy’s Looking Backward (1888) featured characters paying with credit cards more than 60 years before magnetic stripes were invented. The government in George Orwell’s 1939 classic 1984

Of course, for every Neuromancer, there are hundreds of sci-fi works that did not turn out to be prophetic. Some are thought experiments about worlds entirely unlike our own, while others hold a mirror up to this one. Science fiction isn’t about predictions, it’s about stories — exploring the infinite possible futures our world might unfurl into, and the technologies that would carry us there. The best science fiction feels truer than true, familiar to the heart if not the mind, but expanding both.

Sci-fi as UX Design

So science fiction isn’t necessarily all about figuring out the next big technology. But if you’re trying to build the next game-changing tool, platform, or product, science fiction might help get you there. After all, many of the people building blockchain protocols, products, and networks are working for social as well as technological change: moving power to the edges, dismantling destructive hierarchies, giving individuals control of their digital identities, and reimagining how everyone can exchange old and new forms of value in a more transparent, trustful way. That reimagination is also a kind of storytelling.

Cellarius is a transmedia storytelling experience rooted in science fiction. Some of the core goals of the project — blockchain-supported metadata, digitally native IP structures, more permissive licensing, a new kind of content marketplace — could be tested in any genre, but we’ve chosen near-future hard science fiction because we want the Cellarius story to explore the technologies we are helping to build and scale on blockchain. By bringing writers, artists, filmmakers, musicians, and all types of creatives to this project, we hope we can create a more diverse base of users contributing to the Ethereum ecosystem and grappling with its big technical, social, and ethical questions in its early years. This includes thinking about how Web 3.0 technologies could shape the futures of individuals, institutions, and societies — by creating science fiction.

Thinking about human outcomes is the best way to build tools and products. As Sarah Baker Mills wrote in her designing for blockchain deep dive, the human story is too often left out of product discussions, or brought in too late. The people who use and interact with technology are not just customers or marketing categories, and most of them won’t know or care about the underlying machinery, be it the TCI/IP suite of communication protocols that underpin our current experience of the Internet, or the low-level client specs of Web 3.0. People adopt technology if, and because, it will make their lives better or easier in some way: it lets them connect to people, lets them get work done more efficiently, lets them exchange goods or money faster. We need to understand the human context of what we’re making and include a wide range of people in the process, from the very beginning.

Optimism on the Cutting Edge

Many beloved works of science fiction are dystopian and cautionary tales about what could come to pass if we cede too much power to machines or surveillance states. Conflict often makes great stories, and sometimes taking danger or darkness to an extreme clarifies the version we’re living in now. But science fiction can also include optimistic tales of liberating heroes, more equal societies, and deeper knowledge. There is room in science fiction (and certainly in Cellarius!) for optimism: hope, ambiguity, freedom, and love stories.

Likewise, the best possible outcomes of scalable Web 3.0 technologies offer rich opportunities for storytellers. Individuals, institutions, and societies all interact and overlap in science fiction. What will the world look like when large groups of people can coordinate and collaborate without the mediation of a central authority? How will people approach business transactions peer to peer, in the absence of middlemen, with more tools for establishing trust and reputation? What will jobs look like when companies have evolved into networks? How do the dots between these connect in the lived experience of one person?

In fact, some Web 2.0 giants, including Google, Apple, and Microsoft, have hired science fiction writers to present to their employees on “design fiction” and meet with their teams of developers and researchers to workshop ideas. User research and user experience should start with storytelling, and making users and their contexts fully three-dimensional.

Does Sci-Fi Really Inspire Great Ideas? Ask Joe Lubin!

ConsenSys founder and Ethereum co-founder Joe Lubin is a devoted science fiction fan. His three favorite works? The classic 1982 film “Blade Runner,” directed by Ridley Scott — an adaptation of Philip K. Dick’s novel Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep? — and the Neal Stephenson novels Snow Crash (1992) and The Diamond Age (1995). Are there base notes of decentralized architectures and non-hierarchical mesh organizations in these pages? Only one way to find out.