“Yo, Google — Help Save the Mekong.”

“Yo, Google — Help Save the Mekong.”

The case for adapting Google’s Public Alerts program to Southeast Asia’s most at-risk ecosystem

We’ve all seen the commercial. During the 2018 NBA Finals, Google released a promo for its newest AI-enabled service, Google Assistant, wherein celebrities like Sia, Chrissy Teigen, and John Legend are featured making requests of the bot to complete different tasks on their behalf. Just say, “Hey, Google” and it’s done. No doubt a remarkable product that will only continue to raise the bar beyond

Well, if you insist, I have a “Yo, Google” request I would like to make.

Context: Google + India Central Water Commission

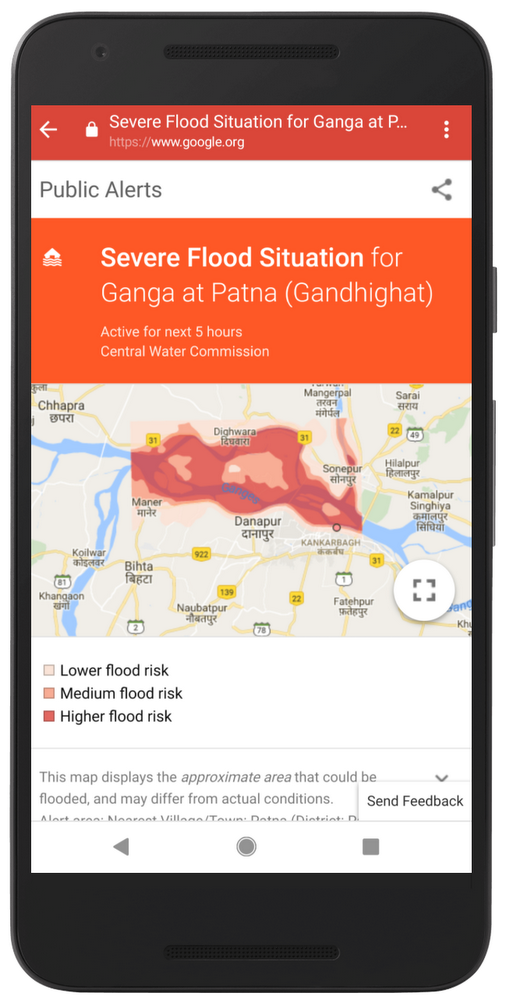

In June, Google announced a partnership with India’s Central Water Commission to apply machine learning tools to diverse data pools related to flood control in the Patna region. The tech company is redesigning its Google Public Alerts service in eastern India’s second largest city — which is also situated on the southern bank of the Ganges River — for the purpose of forecasting and broadcasting information regarding potential floods that could impact almost 2 million residents. Earlier this month, the program sent out its first notification onto the network, in light of heavy rains planned to hit the Ganges.

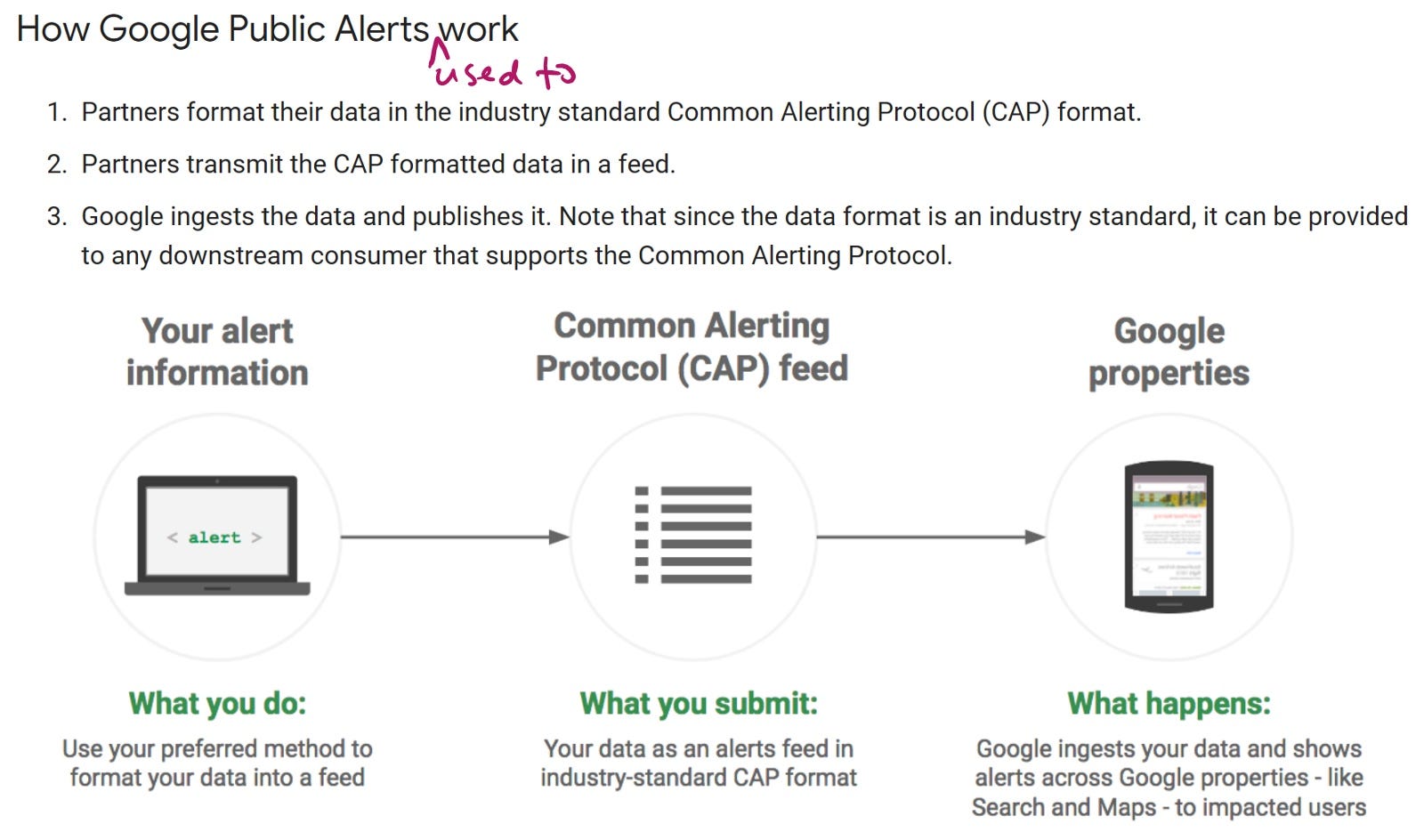

Public Alerts has for 20 years been used purely as a dissemination instrument, through which government organizations in roughly a dozen countries can publish information regarding natural disaster events and emergencies.

However, nowadays, as technology activates every aspect of our planet into a Pokéball of capturable data, private tech companies like Google have evolved to be the world’s Ash Ketchum. Government organizations like the Indian Central Water Commission recognize that Google’s ability to harness and make sense of disparate data sources — think, river water levels, sea level elevations, dam activity schedules, and historical disasters—is the best option for predicting events, preparing the public, and preventing calamity. Casting aside for a moment the over-worked narrative of fuzzy interplay between tech conglomerates and public affairs, this project is a ginormous milestone for a list of arguably adolescent innovations, spanning from machine learning, geospatial mapping, computational agility, satellite imagery, and artificial intelligence. A blog post authored by a Google VP of Engineering explains how data is aggregated and fed into a forecasting model, which uses multi-variable algorithms to create hundreds of thousands of simulations, all while updating the probability distributions in real time to provide and execute the earliest possible warning of a flood. Mind-boggling, enviro-geeky, and also very risky. Google Public Alerts integrates with Google Search, Maps, and Now — applications that many persons blindly take as fact. Even with half a million simulations, can you ever really tame Mother Nature? And what is the cost of misinformation?

OK, time to climb back out of the rabbit hole.

Course of Action: Google + Mekong Region

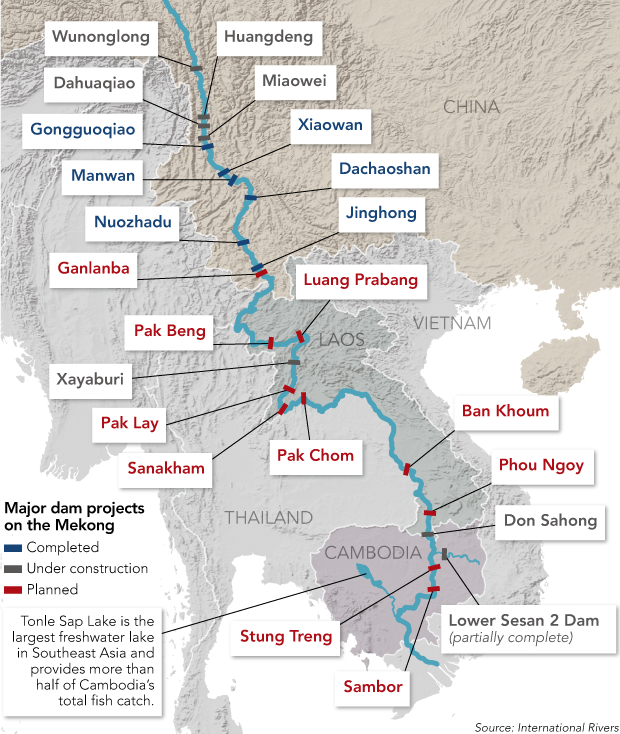

I am explaining all this is because I believe this same technology can and should be tested for and applied to the Mekong River region, which spans from China’s southwestern Yunnan province to the river deltas of Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam. Over 60 million people across Cambodia, Laos, Myanmar, Thailand, and Vietnam depend on Mekong (“Lancang” in China) tributaries for fishing, farming, and transportation — to name a few. Another entity tying these nations together is China. The emergent power’s economic investment into the Mekong region has risen at a +20% clip YoY since 2016. Investment supports massive dam projects meant to drive trade from headwaters in Yunnan to the South China Sea. Recipient Mekong governments, eager to bolster their own economic development, agree to sometimes non-concessional loan terms, catalyzing debt sustainability worries.

Macroeconomics aside, affected citizens are raising concerns about the social consequences of dam-building — Thai fishermen report drops in catches; Vietnamese rice farmers witness water deficits during crucial growing seasons; Laotian dams kill citizens upon collapse; Cambodian residents are relocated to areas lacking irrigation…

Case Study: Laos Dam Failure

The government in Laos has publicly stated its intention to evolve into the “Battery of Asia,” which has led to billions in foreign funding for dozens of massive hydroelectric dam projects throughout the country’s network of rivers. In July, disaster struck when the Xe-Namnoy dam, located in Champasak province near the border with Cambodia and Thailand, overflowed and killed 36 people. Close to 100 Laotian citizens are still missing, and the flood’s subsequent destruction of nearby villages has displaced 6,000 others who are now without sustainable housing. One of the primary partners of the dam’s engineering, a South Korean construction firm, announced it had discovered the upper portion of the dam had washed away only 24 hours before heavy rains caused the catastrophe. Company officials were able to some inform local safety personnel only 3 hours before the floods hit, leaving little to no time for evacuation. If detection and warnings had been made earlier, could lives have been saved?

The dam was one of two structures part of a hydropower project set to become commercially operable in 2019. About 90% of all hydroelectricity generated would be sent to Thailand, which boasts more economically developed cities in need of power sources. Laos hopes that continued investment into power generation will prompt international governing bodies like the United Nations to upgrade its current status from a Least Developed Country (LDC). Disasters like the Xe-Namnoy collapse do not help their case for graduation; moreover, it was reported by Fitch that the amount of public debt Laos has amassed from Chinese-backed infrastructure projects now surpasses the nation’s nominal GDP for 2017. Each Mekong nation now faces unique challenges from accelerated development projects across the River region, and this event in Laos is just one example.

To address these issues, Mekong nations are joining forces to shift the tide toward greater economic self-sufficiency and environmental oversight. Leaders from five nations recently ramped up planning efforts after the most recent Ayeyawady-Chao Phraya-Mekong Economic Cooperation Strategy (ACMECS) summit in 2018, where a five-year Master Plan was announced to promote infrastructure, technological, and human capital investment in the Southeast Asian sub-region. The ACMECS Master Plan will be supported by a self-funded Infrastructure Fund set to launch January 2019. This move represents a stake-in-the-ground backlash against Chinese funding that now connotes toxicity and unwarranted encroachment in the eyes of Mekong representatives.

I believe the timing of this Fund invites a possible use-case for Google’s Public Alerts program. If these governments truly wish to drive the long-term progress of their countries, they must deliver a more innovative approach. This means investment skewed less toward new dam projects and more toward technological build-out and enhanced connectivity. There are many sub-points that I think further this perspective:

- Due to the rapidity in funding approval processes, infrastructure contracts typically lack consummate life-cycle cost analyses and environmental impact surveys.

- There already exists an abundance of Mekong river dam structures in operation, under construction, and planned for development.

- The jury is still out about whether the hydroelectricity generated by these dams outweighs the economic, ecological, and social costs of their existence.

So, what does technological investment entail and/or require, and what is Google’s role?

- An ubiquitous fleet of “smart” Internet of Things (IoT) hardware sensors designed and fastened onto existing dams and incorporated into all approved and pending project budgets going forward

- Strategic partnerships and agreements between Google, national governments, and governing bodies of the Mekong, like the Mekong River Commission (MRC), Lancang-Mekong Cooperation (LMC), and the aforementioned ACMECS

- Coordination and leadership from Google’s Bangkok office to roll out the Public Alerts program in the region, with emphasis on mobile device programming

- Consideration for existing data privacy and transnational data sharing laws of each respective country in the region, specifically pertaining to disaster and emergency services (inviting possible reform, if necessary)

There is, however, one giant consideration looming in the background of this discussion: the People’s Republic of China.

Corollary: China’s Role

It is worth a second reminder that the Mekong River actually begins in Mainland China, under a different name: the Lancang River. Prior to the multitude of hydropower dams the country has helped fund and/or build downstream for its southern neighbors, China developed what is now tallied at a trail of 11 dams inside its own borders. It has both the literal and metaphorical “upper hand” on the flow of water, and this has brought much concern to the surface from both the ASEAN and global community.

Local governments and businesses along the Lower Mekong have called on China to share information regarding water release schedules from their upstream dams, but to almost no avail. Party officials argue that specific dam details are “internal matters.” Only recently did the central government agree to publish partial information during the rainy season months. As a result, farmers, fishermen, and housing commissions are forced to rely mostly on weather forecasts from southern China — a trial-and-error method of constant seasonality imperfections and lack of subsequent evacuation plans.

From China’s point of view, this dilemma seems somewhat counterintuitive. As part of the nation’s much-heralded Belt and Road Initiative, Chinese development banks and corporations have invested tremendous sums of money toward the economic future of their downstream neighbors, touting their efforts as a transnational crusade to lift up the Eastern developing world on the back of China’s rising tide. The following quote from President Xi’s 2017 Belt & Road Forum illustrates the empathetic traits that accompany this infrastructure investment:

“We will not follow the old way of geopolitical games during the push for the Belt and Road Initiative, but create a new model of win-win and cooperation. It will not form a small group undermining stability, but is set to build a big family with harmonious co-existence.”

By all accounts, China’s economic and geopolitical interests are at least partially tied to the future of these nations — so, why the resistance to offering cooperation when it comes to the Mekong River? Why does the word “co-existence” seem to carry an asterisk behind it, as if to ensure limited liability? In my view, issues of river protection, flood prevention, and emergency correspondence should be just as much China’s concern as Mekong countries’.

While environmental impact assessments (EIA) do exist for specific dam projects along the Mekong, there is far less research on cascading effects of dam disruption. River routes tend to follow earthquake fault lines, so the consequence of one dam failure often causes a sequential impact on downstream dam structures. As a result, this domino effect risk will only magnify as countries like China and Laos continue to partner up and construct larger strings of dams, only further justifying the case for cooperation.

How, then, can technology serve as a platform for cross-border synchronization, so that inevitable infrastructure build-up is accompanied by integrative safety measures?

Consideration: Google + Project Dragonfly

This could be an opportune moment for Google to step into a new role, especially as the company sketches possible re-entry plans into China. On August 1, The Intercept released a report uncovering internal corporate plans to launch a censored search engine for the Chinese market. Dubbed with the codename “Dragonfly”, the plans became more colorable in December 2017 following a meeting between Sundar Pichai and a top Chinese official. It would, of course, be a full directional shift from the company’s 2010 decision to exit the country for moral and ethical reasons related to data restriction — the same judgment that is now being put into question, this time with the finger pointed inward.

Several Googlers affiliated with the project have resigned following the report’s release and confirmation, and 1,400 employees have since signed a letter to company executives demanding more details on Dragonfly and more input into decision-making about the kind of work the company pursues. Their reaction is complementary to the plethora of external backlash that has emerged in subsequent weeks.

One thing is for certain: this is a complicated decision. But, if Google ultimately does decide to go forward into China, maybe the tech company could lessen the blow to its ethos by broadening its scope of service offerings in China beyond a simple search function. In fact, to best satisfy the needs of every stakeholder, the current technological void inhibiting aligned development efforts in Southeast Asia and permitting natural disasters along the Mekong River may, in fact, require fill from an outside party like Google. Using AI to create and deliver warnings to local communities against floods and earthquakes caused by weather or dam malfunction is a perfect application of the company’s mission to “provide people with the information they need.”

“We’re also looking to expand coverage to more countries, to help more people around the world get access to these early warnings, and help keep them informed and safe.”

— Yossi Matias, Google VP of Engineering, on Public Alerts

Not only would expanding Public Alerts from South Asia to Southeast Asia be socially beneficial to Mekong river communities, but it would create headwinds for Google, as well. I can think of three:

- Aid toward reconciling its “do no evil” mantra, as a useful project to quell dissatisfaction from company employees

- Improved brand recognition in the developing world, especially as the race for global AI leadership intensifies

- Counterbalance to the somewhat Faustian bargain made with Chinese censorship laws, via providing a platform that operates within and beyond the Mainland firewall

Conclusion: Google + You

One of the most startling, talked-about, and evident headlines of this modern day is tech conglomerates’ omnipotence in our world. Three pieces of media I’ve personally found insightful and telling on this subject is The New Yorker’s playful take on the European Union’s GDPR law, WIRED Editor-in-Chief Nicholas Thompson’s interview with Tristan Harris and Yuval Noah Harari (whose book, Sapiens, I am currently nose-deep), and Brookings Center for Technology Innovation’s June update on China’s progress toward a social credit system.

Certainly, there is a lot that can be analyzed regarding matters of tech anti-trust law, data protection, and the democratization of media. Yet, I believe the more important response is to demand more from those who lend out the world’s information. To not be satisfied with the trajectory of the world, think critically about what we wish was different, and start to request those changes from the entities we seem to ask just about everything else. Just like Kevin Durant, we don’t have to blindly accept what is given — we can change the rules by giving new commands.

The current and future state of affairs along the Mekong River region is an issue of high importance to me— what matters to you? Define your “Yo, Google” request, and at the very least may it serve as a stone cast across the water to create more ripples.

I am currently designing my Honors Senior Thesis on development efforts along the Mekong River, specifically in areas related to investment, technology, regional power, long-term sustainability, and social progress. Any and all advice, input, or collaboration is warmly welcomed and appreciated. If you’d like to get in touch, please drop me a line: [email protected]

Stay curious! — Joe