When Apple has to provide the solutions to screen addiction, the surrendering of our willpower…

When Apple has to provide the solutions to screen addiction, the surrendering of our willpower comes full circle

Apple’s latest iOS 12 software update highlights the availability of Screen Time, a feature claiming to ‘empower users who want help managing their device time, and balance the many things that are important to them.’ It lets you set limits on your access to different apps, and if you need more time, you just double tap and access is granted. Other measurements include how many times you pick up your phone in an hour and how much time you have spent glued to your screen, with a breakdown of time spent on Twitter, Facebook, Instagram, Outlook and the like.

With the average time spent actually looking at our screens being 145 minutes a day, we are not completely oblivious to our digital diets. Acknowledging the side-effects of digital overconsumption gradually seems to be entering public consciousness. 18–24-year-old UK women are the most dedicated users, spending 88.5 hours a monthon average

It is understandable that some might argue that Screen Time presents a step forward in helping us regain control over our screen habits (Google Digital Wellbeing supplies similar metrics). It is making time visible and providing valuable insights into our own behaviour, hopefully spurring critical reflection as the initiator of change. But is there not something slightly discomforting about turning to the same tech firms to effectively stick a plaster over highly addictive design? We are seeking more control over our use of digital tech but turning to the corporates to grant us this permission.

True, Apple doesn’t rely on us being hooked to screen time for its business model but it is making headway in the health sector, with new products marketed to monitor our physiological (Apple Watch series 4) and psychological data. We need to be asking what is the agenda and how might this data be used in the future, because the idea that a new data set will sit there unused seems a little naïve.

The attention economy and addictive design has created a problem — with studies claiming negative effects on our ability to concentrate, stress levels, happiness — and then has closed the loop by providing in-house tools claiming to solve it. It follows the Silicon Valley ethos of disruption — break something and deal with the consequences later, perhaps be the knight in shining armour providing a solution to a health-related or social concern, making us feel more satisfied with life and the world a better place. We are the lab rats that sacrifice our very sense of being for experimentation.

It’s something that former ethical design proponent for Google and ex-Stanford Persuasive Technology Lab employee, Tristan Harris, knows well: ‘[The biggest tech companies] have 100 of the smartest statisticians and computer scientists, who went to top schools, whose job it is to break your willpower.’ Something to remember next time the web is considered as a space to exercise freedom.

Speaking on BBC Radio 4’s Today programme, Harris expanded upon this point drawing issue with their prioritising of digital attention strategists over, for instance, child developmental psychologists. No prizes for guessing who would more likely place wellbeing and mental health of platform users at the forefront of digital design. Working outside of the big corporates now, Harris is galvanising support for the Time Well Spent movement, as Executive Director of the Center for Humane Technology.

Persuasion and rhetoric have a long history in politics, and we are aware that when we hear politicians speak, they are trying to convince us of a particular perspective. Politics is defined by the dialogue of competing agendas. With the most popular social media platforms, agenda isn’t usually on our radar. Instead, we place too much weight on our level of choice and ability to self-determine our next move. To assert willpower, we need to recognise what is affecting our decisions and the influencing factors at play, but we’re not there just yet.

I spent the month of July in a remote part of Catalonia for an artist residency, researching and developing work that focused on the battleground of the attention economy and how our craving for both stimulation and relaxation are exploited in a never-ending scroll of digital feeds. In this place of calm, where time moved slower and the mountains provided stability, I found myself dwelling on the culture of distraction. A key indicator of where our attention lies is in our eye movement, and distraction provokes this movement, keeping us busy and occupied whilst in a strange state of inertia.

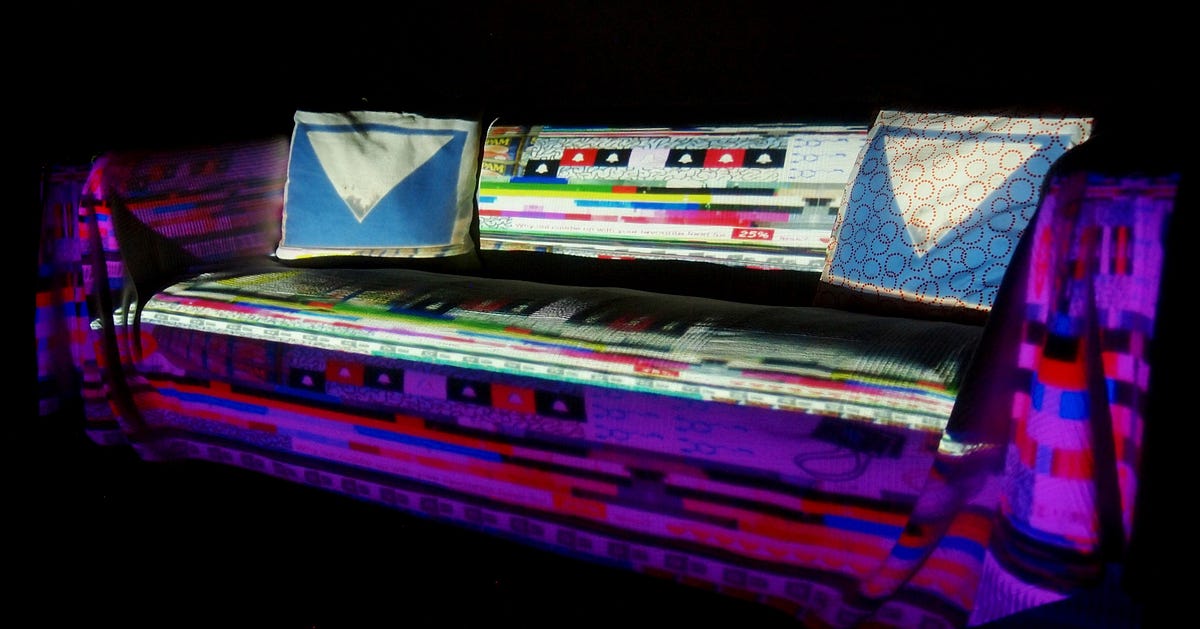

To build a new installation Living in an Inbox, I incorporated eye-tracking into a short film advertising a digital diet, calling upon the language of distraction, infinite scrolling, bombardments of notifications, and ironically our use of digital technology to relax and provide comfort. In the installation, eye movement triggers an obvious flurry of images highlighting how susceptible our attention is to manipulation and how much data we unwittingly give away.

To resist and reclaim control over our digital habits, what we really need to be aware of is how distraction and digital design influences our behaviour and recognise that our willpower needs exercise just like any other element of our health and wellbeing.

The next question is, if we do manage to reclaim our time spent online, no longer anticipating notifications or the constant striving to be as up-to-date as possible, how will we choose to spend our free hours?