The E-Bike Revolution is Coming

What a change twelve months brings. The conversations we’re having about the future of transportation seem like they’d be impossible to imagine a year ago, around the time Bird and Lime started unleashing their electric scooters on the streets of major US cities. The scooters were soon followed by electric bikes, which were first popularized in China before crossing the Pacific.

Naturally, some people opposed this new incursion on streets and sidewalks, and it’s hard to blame them. North American streets typically give a lot of space to automobiles and little to anything else; so pedestrians, already squeezed on their narrow sidewalks, didn’t like scooters whizzing by them or blocking their way.

But where some people were angry, there were others who quickly adopted these new transportation options as they offered easier and quicker ways to get around the urban center — and who can blame them? They’re relatively inexpensive, easy to access, and let riders skip traffic.

The important question in thinking about these new micromobility options — as scooters and e-bikes have been dubbed — is whether they’re having positive outcomes in enhancing mobility, health, and sustainability. It’s too early to answer those questions with regard to scooters, but e-bikes have been around a few years longer, especially in Asia and Europe, where experiences with them have shown some positive outcomes.

How E-Bikes Affect the Transportation System

In 2017, Maarten Kroesen of Delft University of Technology in the Netherlands did a study to find out which modes of travel were being substituted with e-bikes. His research showed that while e-bikes reduce car and transit use, they had the largest effect on regular bike use. However, e-bikes are much more effective at cutting car and transit use than regular bikes, in part because car owners are more likely to use an e-bike than a regular bike.

Kroesen’s review of the previous literature on e-bikes provided a broader and more global perspective. Importantly, he demonstrated how the effects of e-bikes on other transport modes differ based on the local context. In Chinese cities with high-quality transit, e-bikes tend to replace bus trips, while in Chinese cities with poor transit systems, they replace regular bike trips. Meanwhile, in car-centric Australian, Canadian, and US cities, e-bikes mainly replace vehicle trips, while in European cities with high bike use, they replace regular bike and car trips. In short, the layout and dominant transport mode of the city really matters in determining the impact of e-bikes.

Seniors were more likely to own e-bikes in Austria, according to one of the studies Kroesen cited, and his findings indicated the same is true in the Netherlands. He also showed that women are more likely to use e-bikes — a finding echoed by Kirsty Wild of Auckland University in New Zealand.

Wild’s study took place in Auckland, and found that while only 20 percent of regular cyclists were women, they made up 41 percent of e-bike users. The women she spoke to said e-bikes worked better for their lives because they could take longer trips, carry more things with them, and make multiple stops during a single journey — dropping off their kids, going to the shop, and not showing up to work sweaty.

Both Kroesen and Wild’s work suggests that e-bikes could replace a number of trips currently completed with cars. According to Wild, the people in her study would typically go a maximum of 5 kilometers (3.1 miles) on a regular bike, but went up to 15 kilometers (9.3 miles) on e-bikes, meaning they could cycle to a lot more places that they may have previously reached in a car.

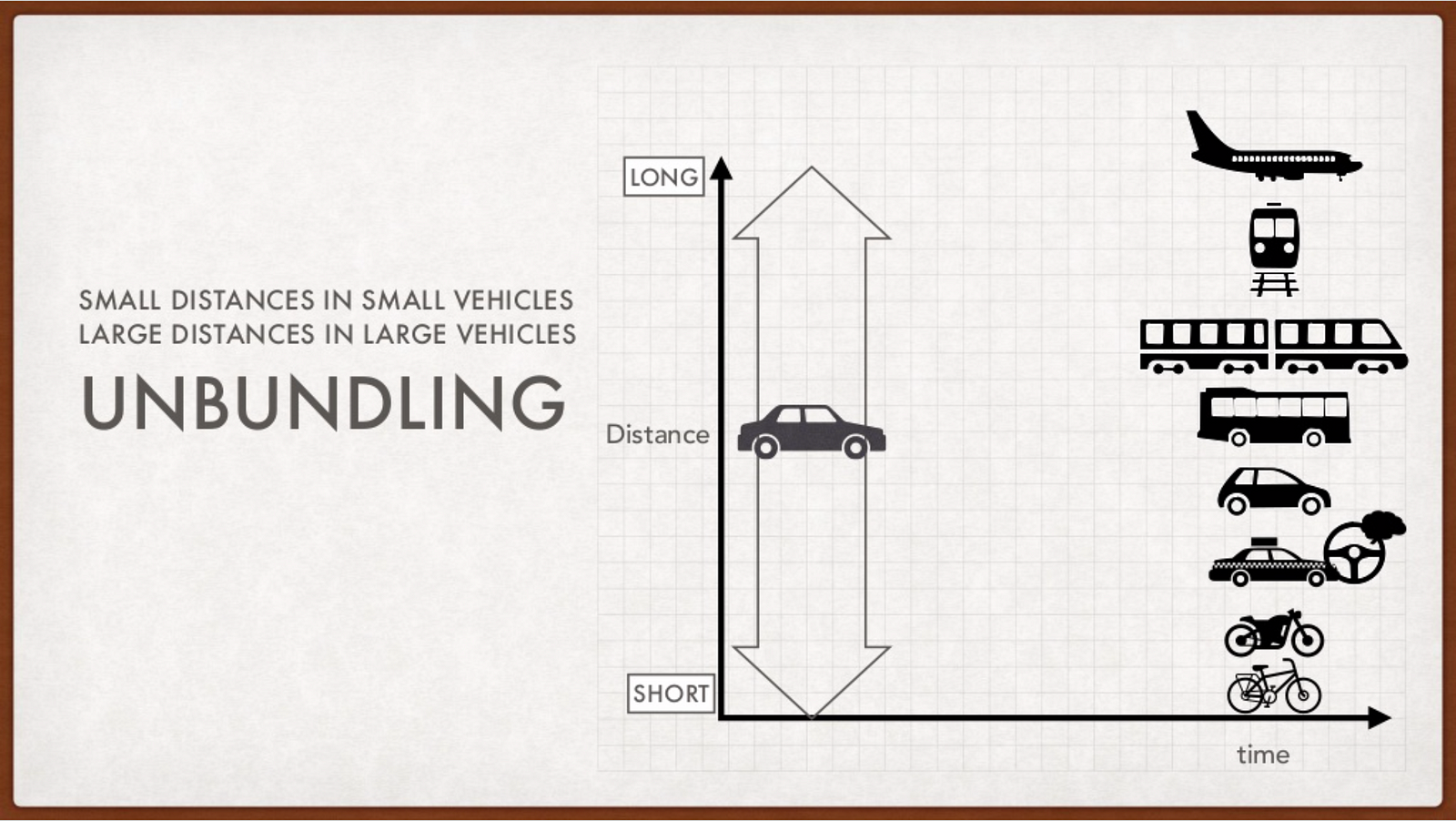

There’s a growing conversation about whether micromobility options are “unbunding the car.” Tech analyst Horace Dediu has talked a lot about the concept, and it’s recently been echoed by Uber CEO Dara Khosrowshahi. Essentially, it means that the car has long been the go-to mode for nearly all trip lengths, but now those trips are being completed with a multitude of different modes that are more appropriate based on the trip’s length.

But Are They Good for the Environment and Health?

If we’re shaking up our transportation system, that obviously presents some important questions: how sustainable will the new system be, and will it be good for average people?

The first question is particularly important in light of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change’s latest report which lays out the disastrous consequences that we’ll experience if we don’t keep warming below 1.5ºC (2.7ºF), which will require a global emissions cut of 45 percent by 2030. The transportation sector is the top emitter in the United States, in part because SUVs have gained a greater market share in its auto-dominated cities, so any new system needs to drastically reduce emissions — and fast.

A shift away from cars to e-bikes would help to bring emissions down because not only are e-bikes battery-powered, but they also take a lot less energy to move — they’re much, much lighter. And, as Kroesen’s review of previous research indicated, that’s likely the impact they would have in car-centric North America.

The bigger question is whether e-bikes replacing transit and regular bikes is something we should accept. With regard to transit, we obviously don’t want ridership numbers to go off a cliff because that could make it harder to campaign for more transit funding and expansion, which is desperately needed in North America; but if e-bikes are the better mode for the trip, should they really be discouraged?

The same goes for regular bikes. E-bikes use energy where regular bikes do not, and if people switch to e-bikes they may not get as much exercise during their commute as they would on a regular bike, especially if they’re using an e-bike with a throttle instead of one that simply gives the cyclist a boost as they pedal. Yet if the e-bike allows people to take more trips on a bike instead of a more energy-intensive mode, that could be a good thing, and Kroesen indicated a previous study which showed that e-bikes still allowed people to reach “the medium-intensity standard” of physical activity — the same as with regular cycling.

Plus, just as bikes can improve mobility access for seniors and disabled people, there’s no reason to believe that e-bikes couldn’t extend their access, allowing them to reach destinations even farther from their homes.

Changing How We Think About Mobility

That doesn’t mean that everyone’s happy with e-bikes. Prominent cycling advocate Mikael Colville-Andersen called e-bikes “white privilege gadgets” in a controversial tweet earlier this year, dismissing their potential benefits. And as they’ve invaded North American streets, there have been other voices decrying them as an unwanted incursion.

However, just as e-bikes gained popularity in Asia and their sales continue to soar in Europe, they will likely also become more common in North America. And while micromobility has caused some difficulties in its first year, its adoption is also prompting fascinating new conversations about the future of transportation in North American cities.

Two years ago, everyone seemed to think self-driving cars were going to revolutionize the city and extend the dominance of the automobile; that seems far less likely today, after admissions that the technology isn’t developing as quickly as its boosters led us to believe have caused the excitement to wane.

Instead, the attention has turned to micromobility, and right at the perfect time. We need a more sustainable transportation system, and adopting scooters and e-bikes for more trips would help us to achieve that. The explosion of these services is forcing cities to have conversations about their micromobility infrastructure, the companies are funding groups pushing for bike lanes — if not trying to pay for the bike lanes themselves — and planners are even questioning how we perceive streets.

It’s still far too early to say what the future of mobility will look like, but there should be no doubt that things are changing. E-bikes could play a big role in that future, as research suggests they would bring benefits in terms of sustainability, equity, and possibly even health. The next few years will hopefully see a fundamental shift in how we think about transportation. We desperately need it.