So what exactly is Vlad’s Sharding PoC doing?

So what exactly is Vlad’s Sharding PoC doing?

I had a chance to work with Vlad Zamfir and Aditya Asgaonkar on the continuation of Vlad’s Berlin hack this weekend.

Now I can shed some light on what his prototype was actually showcasing in Berlin, what it was not, what was built in SF, and how it all works under the hood.

The Proof of Concept (PoC) comprises an implementation of a hierarchical sharding protocol, messaging and message routing between shards, and cross-shard transactions on top of the messaging protocol that guarantees the impossibility of finalization of atomicity failures. More specifically, if a transaction touches multiple shards, it will ultimately either be finalized on all of them, or be orphaned on all of them. The PoC is not yet concerned with Proof of Stake (in particular, it doesn’t implement Casper CBC), wallet or light client.

We published and open sourced the code. Here’s the link to the last commit as of the time we presented the demo (it lacks some visualization improvements that Vlad has locally).

The core component of the PoC is a fork choice rule. It needs to be designed in such a way that for any message sent between two blocks in two shards, either both blocks are in the chosen forks in their corresponding shards, or neither is.

Vlad built the initial fork choice rule between two shards while at Berlin hackathon. The goal for the Eth SF hackathon was twofold: a) extend it to an arbitrary number of shards with arbitrary configuration and b) build messages routing, so that if one shard wants to send a message to another shard that is not its neighbor, it can send the message along the path in the shards hierarchy, the message will be properly routed, and the atomicity guarantees are still satisfied.

The stretch goal was to also design dynamic topology rebalancing to reduce traffic in the network. For example, if it is found that some shards that are a few hops away from each other send a lot of messages to each other, the topology will be adjusted so that those shards are closer to each other.

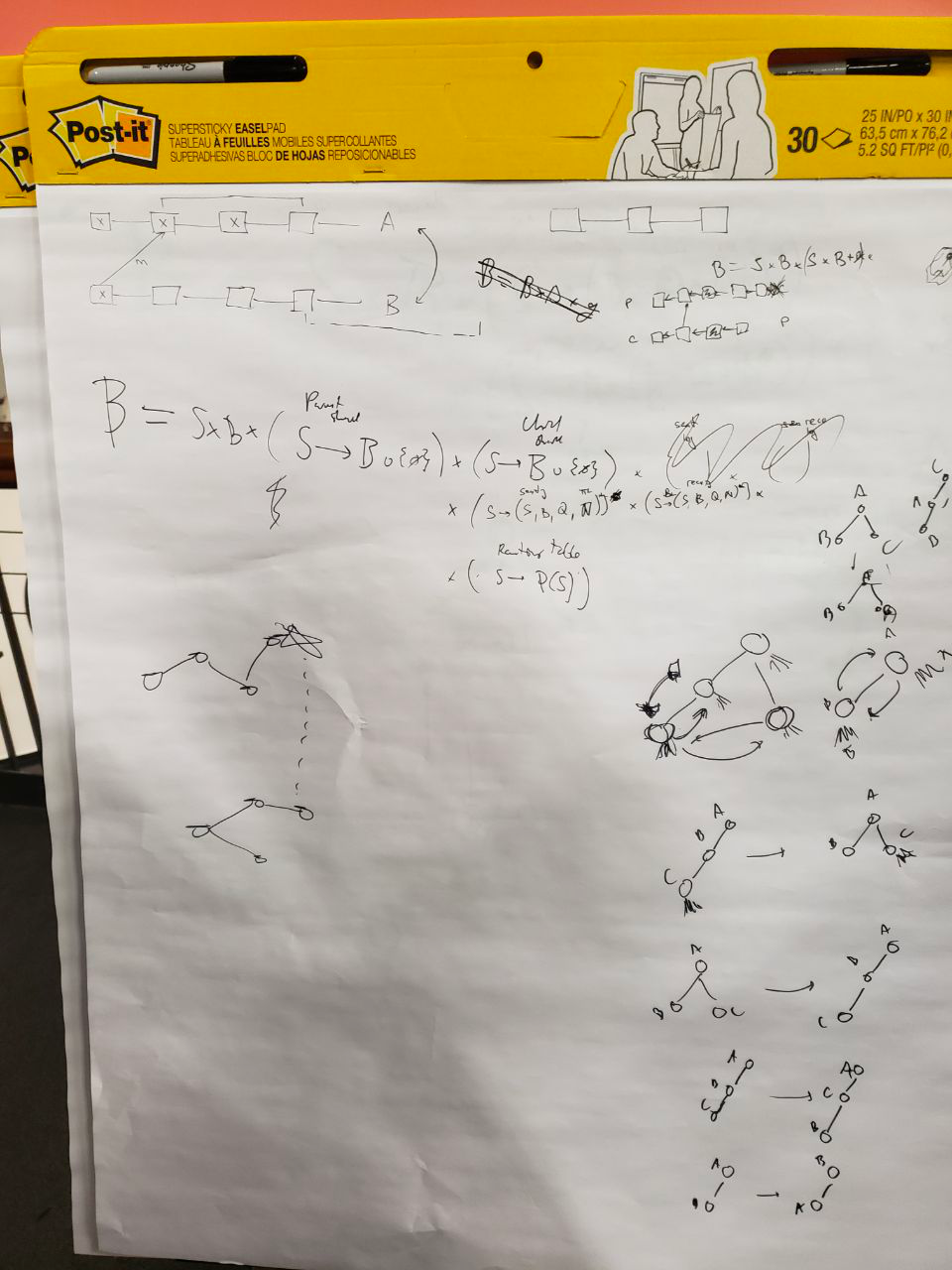

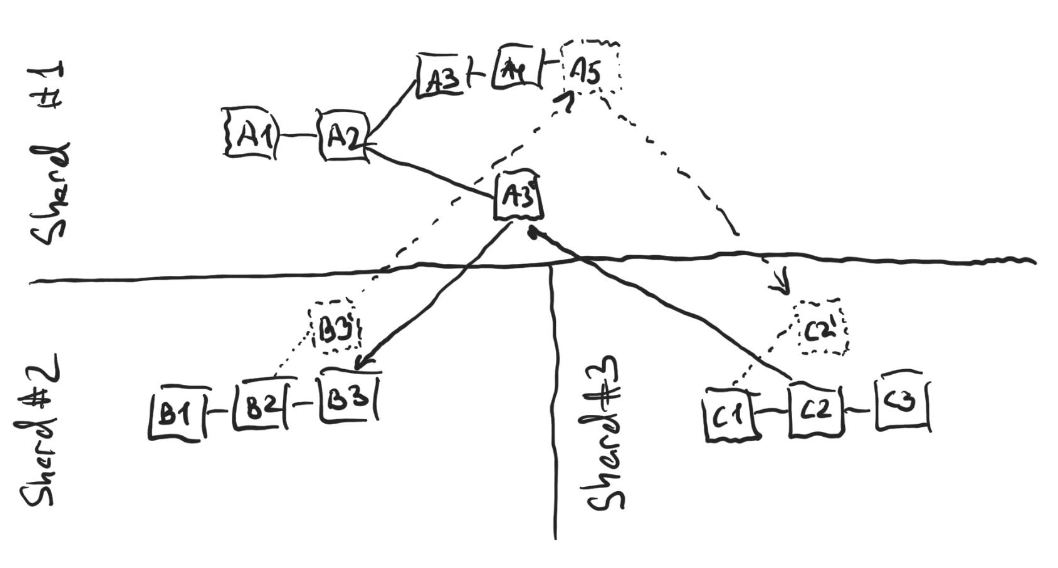

Here’s our whiteboard’s photo after Vlad’s initial explanation:

It contains some core ideas: parent-child relationship and messaging between shards (the two blockchains at the top left, and two at the middle left), the structure of a block, and how the shards hierarchy can be changed (demonstration on the right).

Let’s dive in into how the fork choice rule, message routing, and dynamic rebalancing are implemented, and what challenges they present.

Fork choice rule

Let’s for now assume a static hierarchy of the shards, and only consider two shards. Each block in each shard is defined by

- The shard ID;

- A link to the previous block in the shard;

- The ID of the parent shard;

- The IDs of the child shards;

- sent log: A map that maps a neighbor shard ID to a list of messages that have been sent to the neighbor shard ID from any block in the current shard prior to or including this block;

- received log: A similar map from shard ID to messages received from other shards;

- source map: A map from shard ID to the last block known to the block producer in the corresponding shards, according to the fork choice rule.

The maps in (5) and (6) contain each message in the following format:

- Target shard ID; Note that this shard ID is not necessarily the same as the key in the map (either sent log or received log) the entry is associated with. The key is the neighbor shard from which or to which the message is directly sent while the Target shard ID is the final destination of the message.

- Target block, or base (each message has a specific block it is sent to in its target shard);

- TTL — the maximum distance from the block that will ultimately include the message to the base block;

- Payload

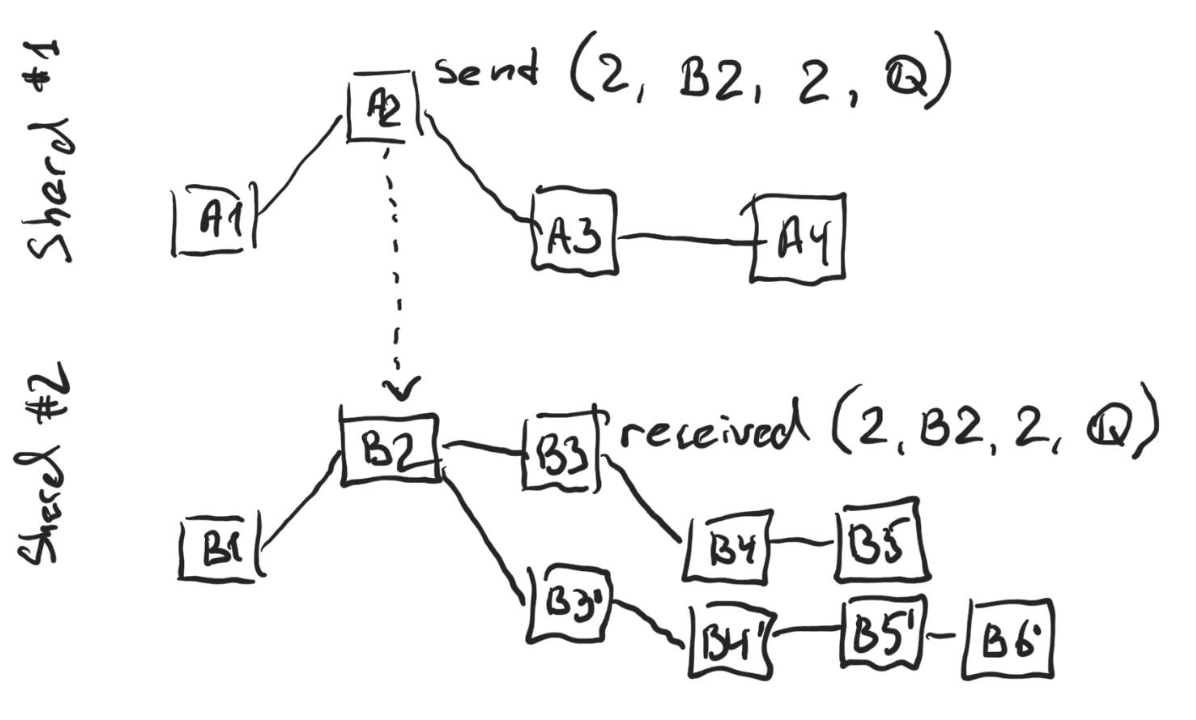

On the figure above time goes from left to right, so A1 and B1 are the genesis blocks. On all the figures in this write-up, the timeline in each shard is independent.

There’s a message in the sent log of block A2 that has B2 as its base. That, in particular, means that B2 already existed by the time A2 was published. While not shown on the figure, the message is also stored in the sent log of blocks A3 and A4, and all the future blocks that have A2 in their chain. The message was received at B3 and thus is also in the received log of all blocks that have B3 in their chain.

The shards have a hierarchy, so each shard has a parent except for one, which is the root shard. We assume on the figure above that Shard #1 is the parent of Shard #2.

Observe that there is a fork in shard #2, and so the fork choice rule would kick in to decide on what chain is the accepted chain. The fork choice rule works in the following way: if a shard doesn’t have a parent (like shard #1), then a regular GHOST rule is applied.

Otherwise, first messages that are inconsistent with the selected chain on the parent shard are filtered out, and then the GHOST is run on the messages that are left. You can find all the rules for filtering out messages in the method is_block_filtered in fork_choice.py, but some important rules are:

- If in the parent shard there’s a block on the selected chain that sends a message to the child chain, any block that is further than TTL blocks in the future from the base block of the message and still doesn’t have the message in the received log is filtered out. On the figure above blocks B4’, B5’ and B6’ are all filtered out, because the message that targets B2 is not in their received logs, and they are all 2 or more blocks away from B2. After the messages are filtered out, GHOST is executed, and the chain with B5 at its tip is chosen as it is now the longer chain.

- If a block on the child shard sent a message to some block that is on the selected chain in the parent shard, and such message is not received within TTL blocks on the parent chain, the block on the child chain gets filtered out.

- Any block on the child shard that sends or receives messages to/from a block in the parent shard that is not on the selected chain is filtered out.

Note that blocks are always filtered out in the child shard, no matter in what direction the message that causes the filtering goes.

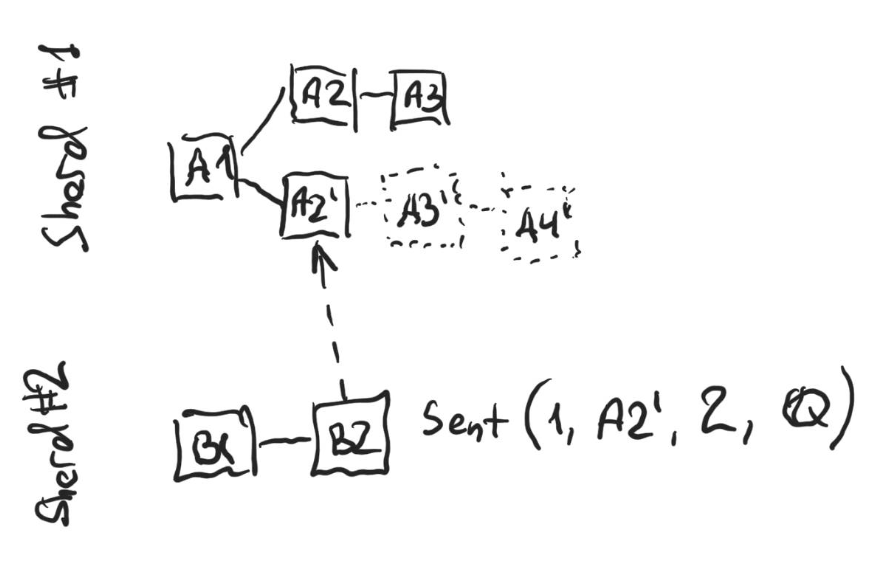

There are also some rules on what blocks are considered to be valid, those can be found in method is_valid in blocks.py. Most notably, a message on the parent shard cannot attempt to send a message to the child shard that would result in filtering out some blocks from which other blocks in the chain on the parent shard have received messages. Neither can two messages in a sent log target two blocks in the same child shard such that neither block is in the chain of the other.

On the figure above blocks A3’ and A4’ are not published yet. The block A2’ is not on the selected chain in Shard #1, since the chain with a tip at A3 is longer. Thus B2 that sends a message with the base block A2’ is filtered out. However, once A3’ and A4’ get published, for as long as at least one of them contains the message from B2 in their received log, B2 will reappear on the selected chain in the child shard.

From the rule (3) in the definition of the fork choice above it follows that a single message from a parent shard that has as its base a block that is not presently on the selected chain in the child chain can trigger a cascading effect of many blocks being filtered out. In the extreme case, if a message uses the genesis block as its base, all the descendant shards will get all the blocks filtered out. This is prevented by the fact that some messages are sent between the child and the parent shard, and as mentioned above it is illegal to publish a message that would result in filtering out a block from which a message was received or to which a message was sent in any block in the chain.

The fork choice rule above is at the core of atomic transactions. A transaction originates at some shard and sends a message to some other shard, and because of the rules above either a block that sends the message and a block that receives the message are finalized or no block that sends the message and no block that receives the message are finalized. Finalization of an atomicity failure is impossible.

Messages routing

Everything up to here is what Vlad built in Berlin. The EthSF project started from generalizing the setup to arbitrary shards configuration. Then we built messages routing. In the original idea, Vlad assumed that each block is extended with a routing table that contains the next hop for each destination shard, but we got convinced that it is not needed since it can be recomputed realtime from parent and children shard IDs and the source map.

For as long as the topology of shards is static, the idea is rather straightforward: every message contains a target shard ID. A block is only considered valid if, for every new message in the received log that doesn’t have the current shard as its target shard, there’s a corresponding new message in the sent log that is sent to the next hop on the way to the target shard.

Importantly, from the fact that for every message it is guaranteed that either both the source and destination blocks are finalized or neither is finalized it follows that for a multi-hop sequence of messages either all the blocks the messages go through are eventually finalized or none is finalized.

On the figure above the dotted blocks do not exist yet. At some point in the past a message from C2 was sent to shard 2 through shard 1, was received at A3’ (at which point A3’ was on the selected chain, meaning that A4 didn’t exist yet), and immediately forwarded to shard 2, where it was ultimately received at B3. Then A4 was published on shard 1 making A3’ not be on the selected chain any longer. Once this happened, the selected chain on shard 2, which had B3 as its selected tip before, now has B2 as its selected tip, since B3 receives a message from a block not on the selected chain of its shard. Similarly, C2 and C3 are not on the selected chain in shard 3 any longer, and the entire selected chain on shard 3 now consists of just the genesis block C1.

As B3’ gets published and sends a message to shard 3, it gets rerouted via shard 1. In the example above A5 routes it, and C2’ receives. At this point B3’, A5 and C2’ are all on their selected chains. If a couple more blocks get published on top of A3’, then A5 will get orphaned, and with it will B3’ and C2’, while B3, C2, and C3 will now become the selected chains. Importantly, as this happens, at any given instance of time from the perspective of any observer the following is true:

- Either all C2, A3’ and B3 are in the selected chains of their shards, or none is (and thus either both hops of the message are acknowledged, or both are not);

- Either all B3’, A5 and C2’ are in the selected chains of their shards, or none is.

Dynamic rebalancing

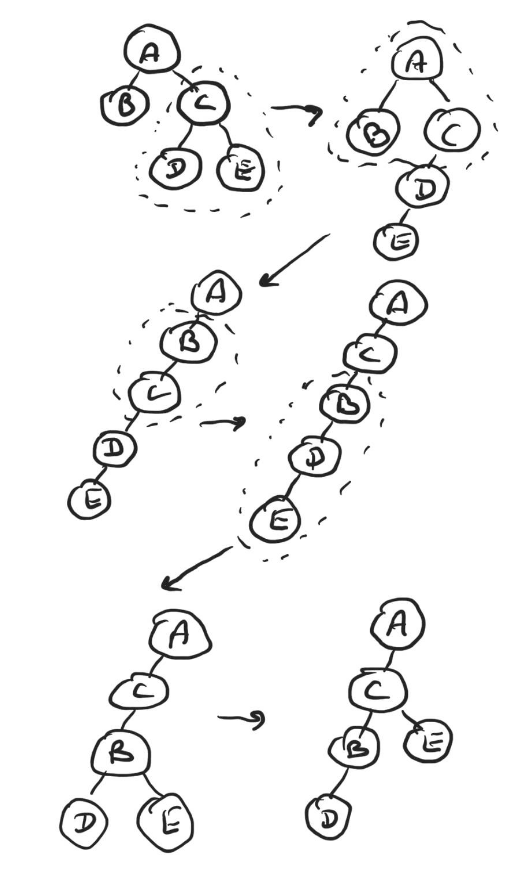

Message routing was finished rather early, and we started working on the dynamic rebalancing. There are three operations that, if all supported, enable reconfiguring from any configuration to any other configuration.

To prove it one can show that using the latter two operations it is always possible to convert any configuration into a configuration in which each shard except for one has exactly one child, then an arbitrary permutation can be applied using the first operation, and that all operations are reversible.

In this PoC we only implemented the second operation, that moves one immediate child of a shard to become a child of another immediate child of the same shard.

I do not have a formal proof in my head that dynamic rebalancing doesn’t cause any fundamental problems with the fork choice rule, and started building it having only a simple intuition that the messages that the parent shard sends to its children have the same atomicity guarantees as any other message, and thus either ultimately the reconfiguration is committed, or rolled back.

Consider a parent shard A that moves its child B to become a child of its another child C. In practice the first obstacle was that once A publishes a block that sends the rebalancing messages to B and C, it doesn’t recognize B as its immediate child any longer, but until C has received the message neither does C. Thus if a message that targets B arrives to any block on A without having a routing table, the source map with parent and child IDs is not sufficient to route the message. At the same time, rerouting such messages to shard C is safe, since it will not arrive to C (won’t appear in the received log) until the block that has the message with the instruction to accept B as a child in its received log.

We addressed the issue of not having sufficient information to route to shard C by introducing the routing table into each block, and Vlad was very happy that he called out the necessity to have the routing table early on.

The second challenge is that in the absence of rebalances the fork choice rule would start from the root shard, and traverse the shards down, using the tip and the selected chain found in the parent shard to filter out messages in the child shard. With dynamic rebalancing, the parent-child relationship is not defined globally anymore. In the current prototype, we compute the tip and the selected chain for the parent shard separately for each block. It doesn’t affect the runtime too much due to caching of the results, but would cause problems if after few reorganizations we end up in a situation in which during some time frame some shard A was the parent of B, and during some other time frame B was the parent of A. With the current implementation it would result in an infinite loop. Vlad presumably found some modification to the fork choice rule that doesn’t suffer from this problem, but he explained it to me at 3:00 am, while I was debugging some consistency violations, so I would lie if I say I understood his idea well. He almost built it though in the morning and it looked promising but didn’t finish fixing all the bugs before the demo, so we went with my infinite loop-prone fork choice rule.

From committing the first implementation of the rebalancing in the evening until almost 6 am there was a lot of debugging and pain figuring out the interaction between the fork choice rule and the rebalancing code and improving the visualization (did I mention that we had an absolutely gorgeous visualizer?), but ultimately rerouting, rebalancing and the visualizer were the core of the PoC.

How to play with it

To run the demo just invoke simulator.py with python3. The only dependencies are numpy, networkx and matplotlib, so no need to run the Dockerfile from the README.

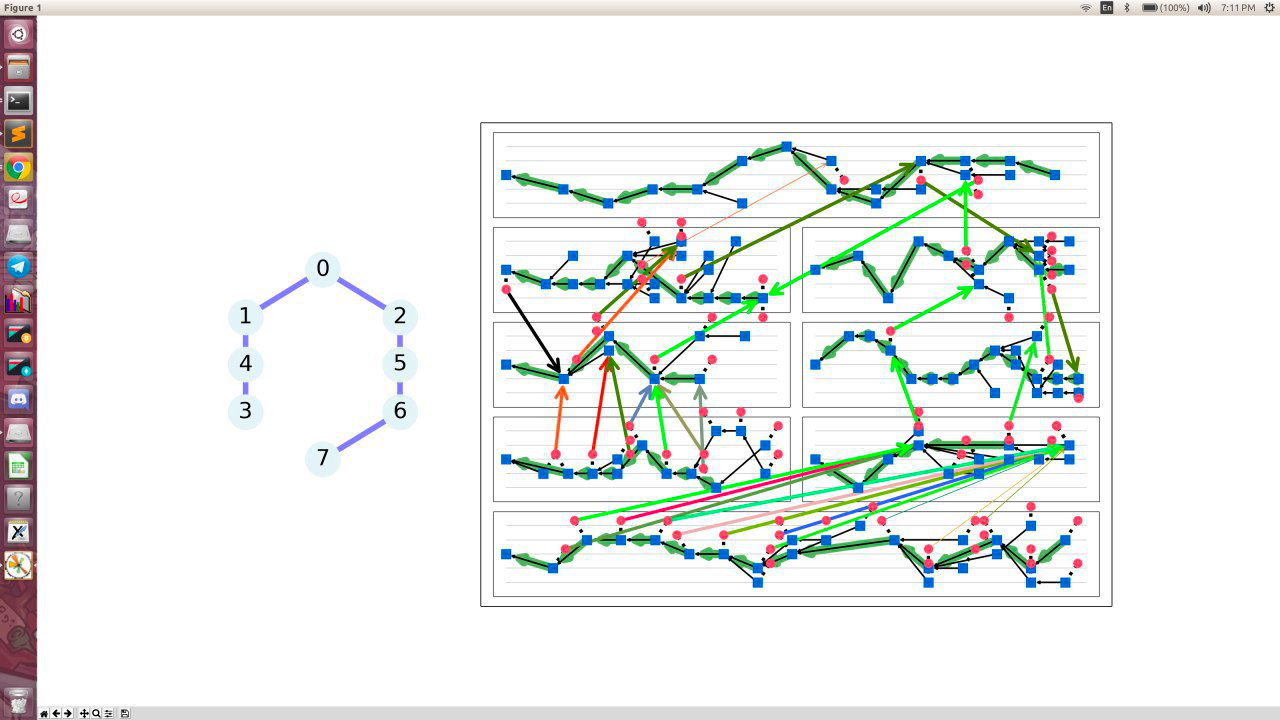

When you run the simulation, you will see something like this:

On the left is the shard topology, and on the right are blockchains in each shard, aligned the same way as the topology on the left (so on the screenshot above the topmost blockchain is shard 0, the two below it are 1 and 2, and the bottommost one is 7).

When you launch it, shards 3 and 4 will be both children of 1, but quickly a rebalancing will happen that will move 3 to become the child of 1. For a split second, you will also see 3 being in some quantum state, that is visualizer being confused by no shard reporting 3 as their child during the time between 1 sending the message and 4 receiving it.

The thick green lines within each shard represent the selected chain.

The thick colored arrows between shards are messages being received. We configured the demo to always send messages between shards 3 and 7 so that as many hops as possible are made, you can disable it be setting RESTRICT_ROUTING to False in config.py.

The thick black arrows are messages with the rebalancing request. In this demo, they will always go from shard 1 to shards 3 and 4.

You can also significantly speed up the demo by setting VALIDITY_CHECKS_OFF to True.

Sometimes (though rather rarely) you will see the think messages lines becoming thin. That means that the blocks with the message were orphaned. For a particular message, you will always either see all its lines think or all thin. It follows from the guarantee that atomicity failure is never finalized, and is never observed from a perspective of any observer at any time. An example of thin lines is the rightmost messages on the screenshot above from shard 7 to shard 6. They are received by a block on shard 6 that is not on the selected chain.

Footnote: If you play with it, it is also worth mentioning that the visualizer has a bug that sometimes shows the message destination incorrectly. It is because the same message can be received by multiple blocks on multiple competing chains, and the visualizer will render the arrows all point at the same block, sometimes resulting a thick line pointing at an orphaned block.

What’s next for the project

If Vlad is right and the fork choice rule does work with dynamic rebalancing, it would provide a foundation to build a sharded blockchain protocol with atomic cross-shard transactions and adaptive topology that adjusts to reduce the number of hops messages traverse on average, while maintaining a reasonable number of neighbors per shard.

We will continue hacking it to support all three rotations and arbitrary rebalances, and then I personally plan to thoroughly test it to increase my own confidence that the fork choice rule works with rebalances. Once that is done, Vlad will hopefully release a formal spec, and anyone in the community will be able to implement it.

So that’s what NEAR will be building now?

While I personally plan to continue working on the PoC, NEAR sharding design won’t use the fork choice rule, messages routing or dynamic rebalancing discussed above. NEAR’s primary goal is to create almost real-time cross-shard transactions while keeping clients sufficiently light that any low-end device can run a node that operates (a part of) the network and processes (a subset of) the transactions. Despite the beauty of Vlad’s design, it doesn’t fit naturally into the architecture we built on top of.

We just started publishing posts on NEAR’s research portal. For the most recent development, read this write-up on our sharded chain consensus algorithm “TxFlow”.

To follow our progress you can use: