Building a Text Editor for a Digital

The interesting exception to this tree-like structure lies in the way paragraphnodes codify their text. Consider a paragraph consisting of the sentence, “This is strong text with emphasis”.

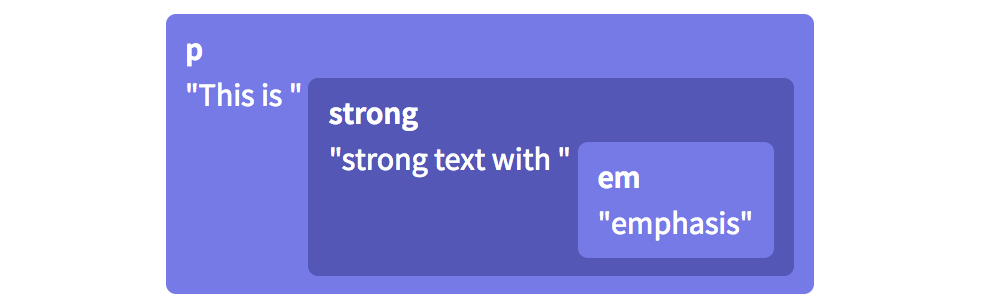

The DOM would codify that sentence as a tree, like this:

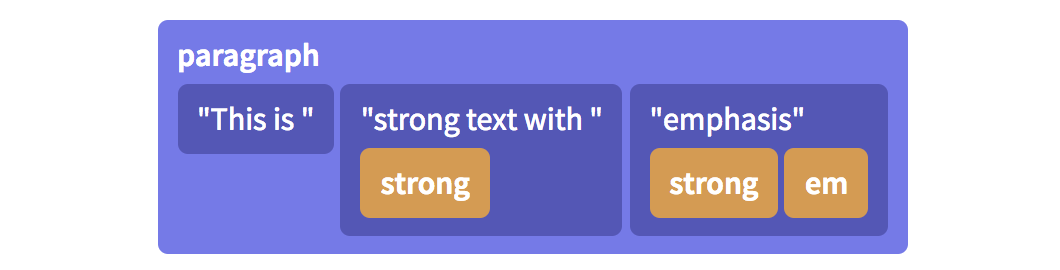

In ProseMirror, however, the content of a paragraph is represented as a flat sequence of inline elements, each with its own set of styles:

There’s an advantage to this flat paragraph structure: ProseMirror keeps track of every node in terms of its numerical position. Because ProseMirror recognizes the italicized and bolded word “emphasis” in the example above as its own standalone node, it can represent the node’s position as simple character offsets rather than thinking about it as a location in a tree. The text editor can know, for example, that the word “emphasis” begins at position 63 in the document, which makes it easy to select, find and work with.

All of these nodes — paragraph nodes, heading nodes, image nodes, etc. — have certain features associated with them, including sizes, placeholders and draggability. In the case of some specific nodes like images or videos, they also must contain an ID so that media files can be found in the larger CMS environment. How does Oak know about all of these node features?

To tell Oak what a particular node is like, we create it with a “node spec,” a class that defines those custom behaviors or methods that the text editor needs to understand and properly work with the node. We then define a schema of all the nodes that exist in our editor and where each node is allowed to be placed in the overall document. (We wouldn’t, for example, want users placing embedded tweets inside of the header, so we disallow it in the schema.) In the schema, we list all the nodes that exist in the Oak environment and how they relate to each other.

export function nytBodySchemaSpec() { const schemaSpec = { nodes: { doc: new DocSpec({ content: 'block+', marks: '_' }), paragraph: new ParagraphSpec({ content: 'inline*', group: 'block', marks: '_' }), heading1: new Heading1Spec({ content: 'inline*', group: 'block', marks: 'comment' }), blockquote: new BlockquoteSpec({ content: 'inline*', group: 'block', marks: '_' }), summary: new SummarySpec({ content: 'inline*', group: 'block', marks: 'comment' }), header_timestamp: new HeaderTimestampSpec({ group: 'header-child-block', marks: 'comment' }), ... }, marks: link: new LinkSpec(), em: new EmSpec(), strong: new StrongSpec(), comment: new CommentMarkSpec(), }, };}Using this list of all the nodes that exist in the Oak environment and how they relate to each other, ProseMirror creates a model of the document at any given time. This model is an object, very similar to the JSON shown next to the example Oak article in the topmost illustration. As the user edits the article, this object is constantly being replaced with a new object that includes the edits, which ensures ProseMirror always knows what the document includes and therefore what to render on the page.

Speaking of which: Once ProseMirror knows how nodes fit together in a document tree, how does it know what those nodes look like or how to actually display them on the page? To map the ProseMirror state to the DOM, every node has a simple toDOM() method out of the box that converts the node to a basic DOM tag — for example, a Paragraph node’s toDOM() method would convert it to a <p> tag, while an Image node’s toDOM() method would convert it to an <img> tag. But because Oak needs customized nodes that do very specific things, our team leverages ProseMirror’s NodeView function to design a custom React component that renders the nodes in specific ways.

(Note: ProseMirror is framework-agnostic, and NodeViews can be created using any front-end framework or none at all; our team has just chosen to use React.)

Keeping track of text styling

If a node is created with a specific visual appearance that ProseMirror gets from its NodeView, how do additional user-added stylings like bold or italics work? That’s what marks are for. You might have noticed them up in the schema code block above.

Following the block where we declare all the nodes in the schema, we declare the types of marks each node is allowed to have. In Oak, we support certain marks for some nodes, and not for others — for instance, we allow italics and hyperlinks in small heading nodes, but neither in large heading nodes. Marks for a given node are then kept in that node’s object in ProseMirror’s state of the current document. We also use marks for our custom comment feature, which I’ll get to a little later in this post.

How do edits work under the hood?

In order to render an accurate version of the document at any given time and also track a version history, it’s critically important that we record virtually everything the user does to change the document — for example, pressing the letter “s” or the enter key, or inserting an image. ProseMirror calls each of these micro-changes a step.

To ensure that all parts of the app are in sync and showing the most recent data, the state of the document is immutable, meaning that updates to the state don’t happen by simply editing the existing data object. Instead, ProseMirror takes the old object, combines it with this new step object and arrives at a brand new state. (For those of you familiar with Flux concepts, this probably feels familiar.)

This flow bothencourages cleaner code and also leaves a trail of updates, enabling some of the editor’s most important features, including version comparison. We track these steps and their order in our Redux store, making it easy for the user to roll back or roll forward changes to switch between versions and see the edits that different users have made:

Some of the Cool Features We’ve Built

The ProseMirror library is intentionally modular and extensible, which means it requires heavy customization to do anything at all. This was perfect for us because our goal was to build a text editor to fit the newsroom’s specific requirements. Some of the most interesting features our team has built include:

Track Changes

Our “track changes” feature, shown above, is arguably Oak’s most advanced and important. With newsroom articles involving a complex flow between reporters and their various editors, it’s important to be able to track what changes different users have made to the document and when. This feature relies heavily on the careful tracking of each transaction, storing each one in a database and then rendering them in the document as green text for additions and red strikeout text for deletions.

Custom Headers

Part of Oak’s purpose is to be a design-focused text editor, giving reporters and editors the ability to present visual journalism in the way that best fits any given story. To this aim, we’ve created custom header nodes including horizontal and vertical full-bleed images. These headers in Oak are each nodes with their own unique NodeViews and schemas that allow them to include bylines, timestamps, images and other nested nodes. For users, they mirror the headers that published articles can have on the reader-facing site, giving reporters and editors as close as possible a representation to what the article will look like when it’s published for the public on the actual New York Times website.