Is it possible to smell music, or taste words?

Is it possible to smell music, or taste words?

When R. listens to music, his mind generates colours that do not exist in the “real” world as perceived by “normal” people. He perceives classical music as “dark brown”, electronic music as mostly “purple”, and symphonic compositions as “red” (Mila ´n et al., 2007). This is the characteristic of one type of synaestesia.

Syneasthesia is a condition in which stimulation of one sensory modality causes unusual experiences in a second, unstimulated modality.

The term synesthesia comes from Greek, meaning “joined perception”. In synesthetes one type of stimulation evokes the sensation of another, such as when hearing a sound produces photisms (that is mental percepts of colors). Examples of synesthesia include visual experienced induced by music and other sounds; experiencing sounds when seeing visual motion; having taste or more accurately flavor sensations when hearing or reading words; and associating the sequence of numbers and months with specific spatial configurations. These few examples capture the diversity of the phenomenon.

Characteristics of Synesthesia

It is generally agreed that synesthesia has the following three characteristics: it is an elicited, conscious percept-like experience that occurs automatically/involuntarily. Cytowic(1997,2002) has some alternative criteria which are

1) involuntary and automatic

2) consistent and generic

3)spatially extended

4)memorable

5)affect-laden

Synesthetic Experiences Are Elicited

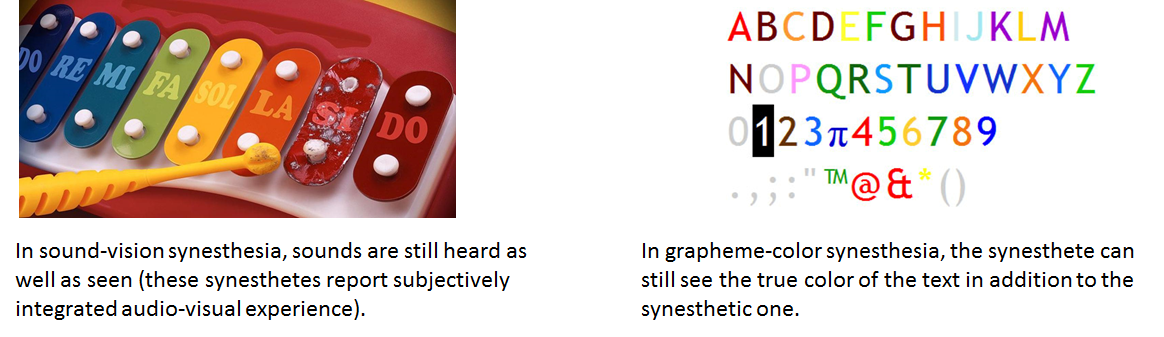

This characteristic distinguishes synaesthetic experiences from hallucinations, which tend to arise spontaneously and unprompted by specific stimuli. It is created helpful terminology of inducer and concurrent to refer to the stimulus that elicits the synesthesia (inducer) and the experience itself (concurrent). One convention is to refer to types of synesthesia in terms of inducer-concurrent pairs, separated by a hyplen (e.g., the term “sound-vision synesthesia” implies that sound is the inducer of synesthetic visual experiences).

The term concurrent implies that synesthesia is experienced concurrently with the incuding stimulus. For instance, in sound-vision synesthesia sounds are still heard as well as seen (these synesthetes report subjectively integrated audo-visual experience). In grapheme-color synesthesia, the synesthete can still see the true color of the text in addition to the synesthetic one.

Synesthetic Experiences Are Like Conscious Percepts

Although this is the central characteristic of synesthesia, it is also the most problematic. Whether or not experience is conscious and “percept-like” is not straightforward to prove, as it is dependent to some degree on the subjective reports of people with synesthesia. It is important that the percept-like nature refers to the concurrent rather than the inducer. Synesthetic experiences may be triggered by also thought alone as in performing mental arithmetic or being in a tip-of-tongue state. In these examples, the inducer is not physically presented but is internally generated.

Synesthetic Experiences Are Automatic

The characteristic of automaticity is synonymous with that of being involuntary. Synesthetes feel that they have little or no control over the presence of their synesthesia. This is almost certainly related to the second characteristics of being percept-like. Our perceptions, unlike most of our imaginations, have the quality of being outside of our control.

Thus, when we see an A we automatically perceive it as a letter rather than as three abutting lines.

When a grapheme–colour synaesthete sees a printed character (e.g., the letter “R”), simultaneously he will perceive a colour halo surrounding the grapheme.

As it is not possible to stop seeing, hearing, or smelling external stimuli unless you eliminate sensory input. The same applies to synaesthesia in the sense that it is virtually immune to any voluntary control.

Consistent and Durable

Consistency-Durability Synaesthetes’ reports suggest that synaesthesia is acquired very early during development and it lasts for a lifetime. Once established, synaesthetic associations remain unchanged; when a synaesthete is presented with a series of inducers across multiple time points, he or she will experience the same synaesthetic concurrents in response to the triggering stimuli. Studies report on consistency measures with test–retest periods of weeks, months, or even years.

For instance, Baron- Cohen, Wyke, and Binnie (1987) studied a case of a synaesthete who experienced photisms in response to spoken language. In a preliminary interview, they asked E.P. to describe in detail the colours she saw when listening to 103 different auditory stimuli (words, letters, and numbers). After 10 weeks they did a retest. The participant’s answers were 100% consistent with respect to the previous experimental session. In contrast, a non-synaesthete participant who was asked to associate colours with the same inducers was far less accurate in her responses. (With a test–retest period of 2 weeks only, the measure of consistency was less than 17%.) In brief, the connection between inducing stimuli and synaesthetic responses is extremely stable over time, and, as is shown later, it cannot be explained by memory performance.

Generic

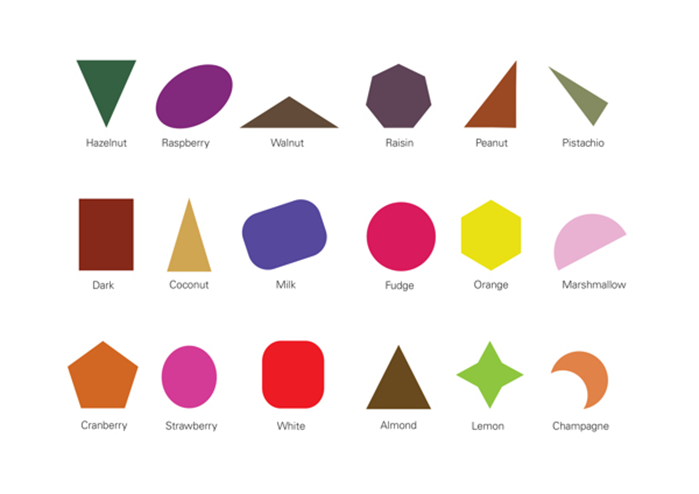

Synaesthetic responses are typically generic; they correspond to basic perceptual qualities such as colour, texture, and fundamental visual forms, tactile sensations, and so on.

The synaesthetic percepts, through their association to the inducing stimulus, may enhance the synaesthete’s memory by serving as additional memory cues. E.g., number– colour synaesthesia may help to remember telephone numbers

Synaesthetic experience is never pictorial or laden with semantic content, it should be noted that there have been cases of letter–colour synaesthetes who, when they hear a word (e.g., “table”), may actually see the letters (T-A-B-L- E) spelled out in colour (Cytowic, 2002).

Spatially Extended

One influential defining characteristic of synaesthesia has been that synaesthetic concurrents are spatially extended meaning they have a particular location in space. Those who experience coloured photisms from listening to music can often describe the direction of the movement of these photisms. Moreover, some individuals with coloured letters can point to the particular location in space where these colours are found (e.g., they may be superimposed on the type-face of written text). It is clear then, that a number of synaesthetes indeed experience a spatial quality to their concurrent sensations

In the case of a synaesthete who experienced tactile sensations in response to gustatory stimulation, the participant used to alter the position of his hands in order to better “reach” for the feeling. All these aspects illustrate the “spatial quality” of synaesthetic sensations. However, this feature is less obvious if we consider those people whose synaesthesia is more similar to visual imagery. This variety of synaesthesia is also completely automatic but the ability to spatially localize is uncertain, given that percepts are not projected externally.

Affect-Laden

Occasionally, synaesthesias can also be related to negative feelings, particularly when the synaesthetic perception is incongruent with the outer reality.(Forexample, when a grapheme–colour synaesthete sees a letter printed in a different colour from that of the associated photism.) and Certain types of synaesthesia are directly related to the emotion. For instance, R., a synaesthete experienced mental colours in response to faces, human figures, and visual scenes with emotional content. Normally the colours experienced were congruent with R.’s emotional assessment of the person or the visual stimulus in question. (R. often used the photisms to refine his opinions about people.) Very rarely, the synaesthetic “aura” experienced by R. was not congruent with respect to the personal relationship that R. maintained with a person — for example, when a good friend of his “had a very unpleasant green colour”. This kind of incoherency was extremely uncomfortable to R. and was accompanied by negative emotions.

Prevelance and Subtypes

According to almost all definitions of synesthesia it is “abnormal” in the sense of being statistically rare, although not in the sense of being “maladaptive”. Synesthesia is not a widespread condition. It’s somewhere around 1 in 2000 (0.05%)

There are some demographic aspects of synesthesia that ought to be mentioned. A series of authors have been reported high incidences of synesthesia among people dedicated to artistic and/or creative professionals and hobbies. 24% out of the 192 synesthetes who participated in the research were professional artists or had a career linked to the arts.

Familial Condition

A large number of authors agree that synesthesia is a familial condition. Its reported that 36% of synesthetes participating in this large-scale study informed having at least one biological relative with synesthesia.

Types of Synesthesia

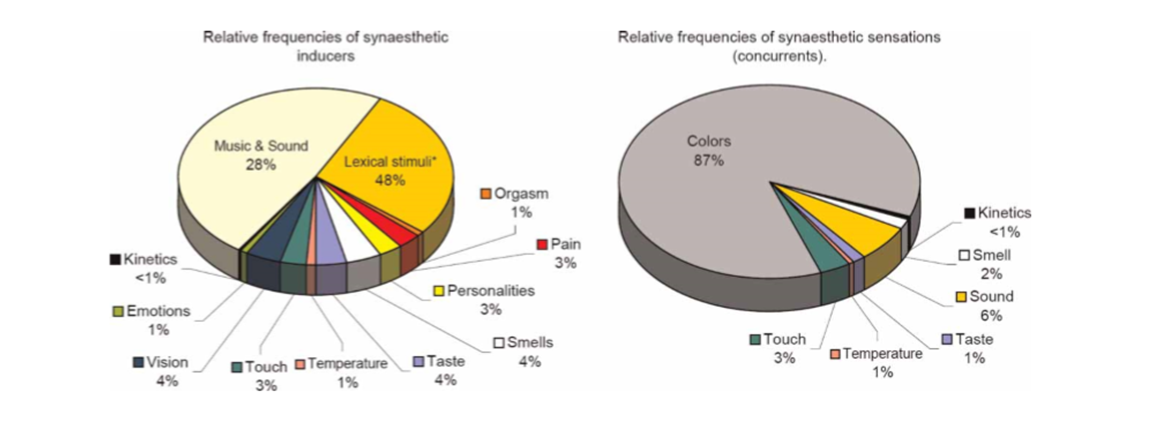

As far as different subtypes of synaesthesia are concerned, all the authors agree that the most frequent modality of synaesthesia is the one induced by lexical stimuli, such as numbers, letters, and words. For instance, in the study by Rich et al. less than 2% of the interviewed synaesthetes did not experience synaesthesia in response to lexical stimuli (words, phonemes, or graphemes) and only presented other kinds of synaesthesia. If lexical stimuli are further subdivided into more specific categories, the days of the week turn out to be the most frequent synaesthetic inducers as you can see in the table.

On the other hand, nonlexical modalities of synaesthesia are much less frequent. Up to 50% of synaesthetes experience synaesthesia in more than one sensory modality. (For example, “lexical” synaesthete can “see colours” when seeing, hearing, or merely thinking of numbers and letters.) Even though for the majority of synaesthetes the synaesthetic sensation is colour, there are reported cases of smell, tactile sensations, sound, taste, and proprioception as concurrent percepts.

There are two major categories of synaesthesia:

1. Cognitive synaesthesia: Photisms or other synaesthetic perceptions are induced by stimuli associated to symbolic meanings, transmitted within specific culture (graphemes, phonemes, people’s names, week days, etc.).

2. Synaesthesia “proper”: Stimuli of one sensory modality are perceived simultaneously and involuntarily through an additional sensory channel (e.g., seeing music)

The other categorizationof synaesthesia is like intramodal synaesthesia. (the inducer and the synaesthetic response belong to the same sensory modality, e.g., when graphemes are perceived as coloured) vs. intermodal synaesthesia (the stimulus induces a concurrent in a different modality, e.g., tactile sensations elicited by taste).

Another important aspect of synaesthesia has to do with the mode of experiencing synaesthetic sensations. According to Dixon et al. (2004), there are at least two qualitatively different varieties of visual synaesthesia. Projector synaesthetes perceive their photisms as located in external space, usually being projected onto the eliciting stimulus (e.g., a grapheme in lexical synaesthesia). On the contrary, associator synaesthetes observe synaesthetic colours in their mind’s eye; there is no external projection of the photisms.

The photisms somehow disrupt the ability to name the grapheme colour, while the real colour interferes little or not at all with the ability to name the photism. On the other hand, the “associator” synaesthetes were faster at naming the grapheme colour.

Positive and Negative Aspects of Synesthesia

The authors also interviewed the participants about potential advantages and disadvantages of synesthesia. The majority of synesthetes (71%) perceived their condition positively, claiming that synesthesia enhances their memory skills, eases data organization, and provides a source of mental pleasure and creative inspiration. Approximately one third of those interviewed mentioned some negative aspects, mainly synesthesia being a source of confusion due to incongruence between synesthetic perception and physical reality (e.g., when the meaning of a word does not fit with the elicited photism). Lexical synesthetes reported contradictory feelings caused by a negative disposition towards persons whose names were perceived in negative mental colours. A small number of synesthetes complained about sensory overload and feelings of discomfort because of “being different”.

References:

Hochel, M. & Milan, Emilio, G. (2008). Synaesthesia: The existing state of affairs Cognitive Neuropsychology, 25:1,93–117, First published on: 05 Fubruary 2008

Hubbard, E., M., & Ramachandran, V.S. (2005). Neurocognitive Mechanisms of Synesthesia. Neuron, Vol. 48, 509–520, November 3, 2005.