Buyer fragmentation matters: $1bn marketplaces have at least 1 million buyers

Buyer fragmentation matters: $1bn marketplaces have at least 1 million buyers

This is the third in a series of essays on my learnings and findings from a six month marketplace research project. There has been a lot written about online marketplaces and our goal was to test these theories by exploring patterns from a broader set of companies. We started by making a list of every marketplace founded, creating a list of 4,500 companies from Crunchbase, Pitchbook, and other sources. We then collected public data to classify and compare these companies, and identified the characteristics of successful marketplaces (

Marketplaces typically aggregate suppliers at scale to provide competitive prices and broad selection to buyers. Amazon, Airbnb, and Uber connect millions of sellers, hosts, and drivers to tens of millions of buyers, travelers, and riders.

Conventional wisdom is that marketplaces benefit from high fragmentation in demand and supply to drive perfect competition in both sides of the marketplace. Our data indicates that aggregating a large number of buyers is far more important than a large number of suppliers.

Both web and mobile adoption have enabled new services to aggregate millions of buyers (e.g. eBay on the web, Uber on mobile). Our data shows that since 1990, entrepreneurs have shifted their focus as new platforms emerge (Web 1.0, Web 2.0, mobile). We found that one of the most popular marketplace categories in the 1990s also had the highest failure rate: wholesale trade (i.e. business to business marketplaces). There weren’t enough buyers online in 1999 to build a large B2B marketplace business, but this is no longer true in 2018.

A large, fragmented market of buyers is required to build a significant marketplace business

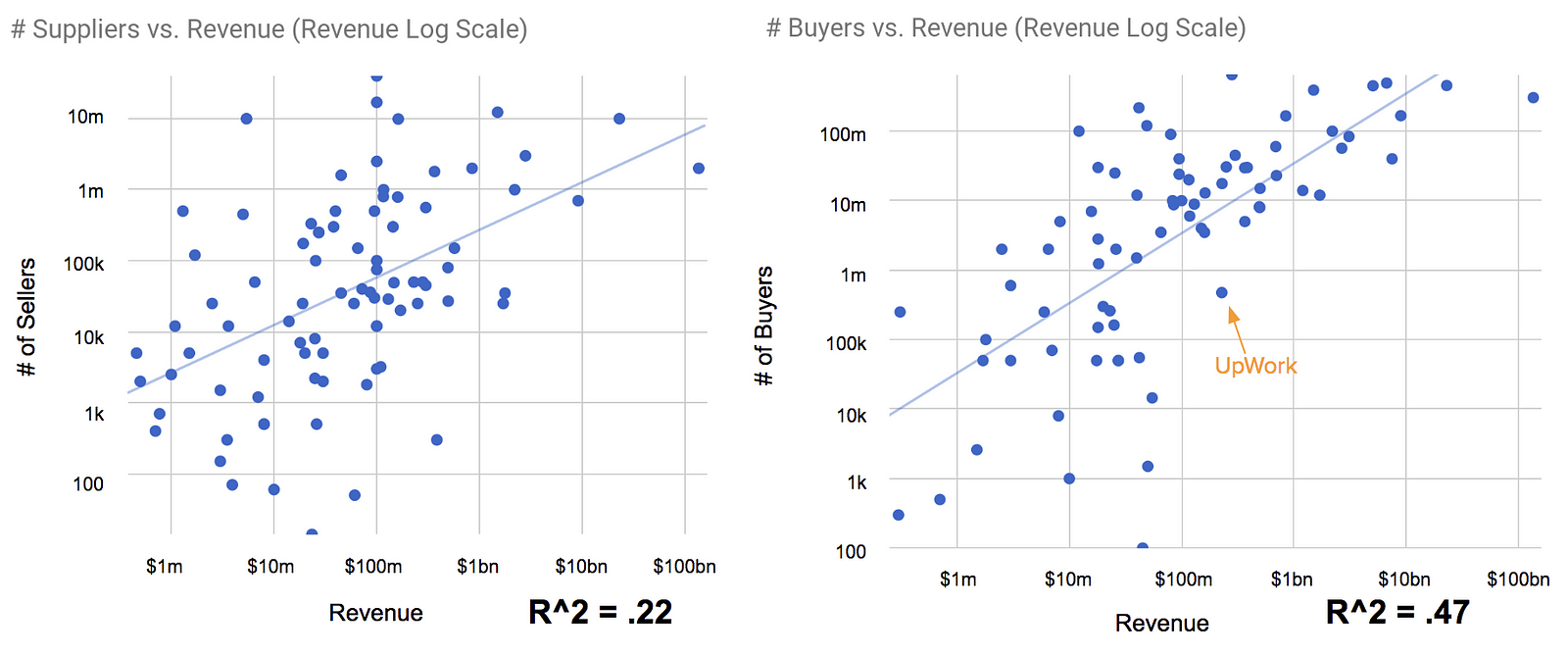

Each dot on the scatter plot¹ below represents a single marketplace and shows the relationship between that marketplace’s revenue and the number of buyers (right chart) or number of suppliers (left chart). There is a much stronger relationship between the number of buyers and revenue than between the number of suppliers and revenue.²

There is only one marketplaces in our dataset that has more than $100 million in revenue and less than 1 million buyers (Upwork).³

Of the top 20 marketplaces, half of them them have fewer than 100,000 suppliers. LendingTree has only 300 suppliers but almost $500m in revenue. Some other notable examples include Coupang (25,000 sellers, $1bn+ in GMV in 2016), JustEat (~82,000 restaurants and $700m revenue in 2017), and Grubhub (80,000 restaurants and $680m revenue in 2017).

Some marketplaces, like Uber, require very high density of supply at a particular location and time. These require millions of suppliers to deliver on the promised user experience (keeping wait times below 5 minutes in the case of Uber). But marketplaces that need millions of suppliers to deliver buyer value are the minority. Of the marketplaces in our dataset with more than $100m of revenue, only ⅓ of these have more than one million suppliers.⁴

Platform shifts have enabled new marketplace opportunities.

New platforms have created opportunities for marketplace businesses by aggregating a critical mass of buyers. eBay leveraged the internet to attract a million buyers by 1999, 4 years after it was founded. Uber took advantage of mobile devices to aggregate a million riders by 2013 (also 4 years after it was founded).

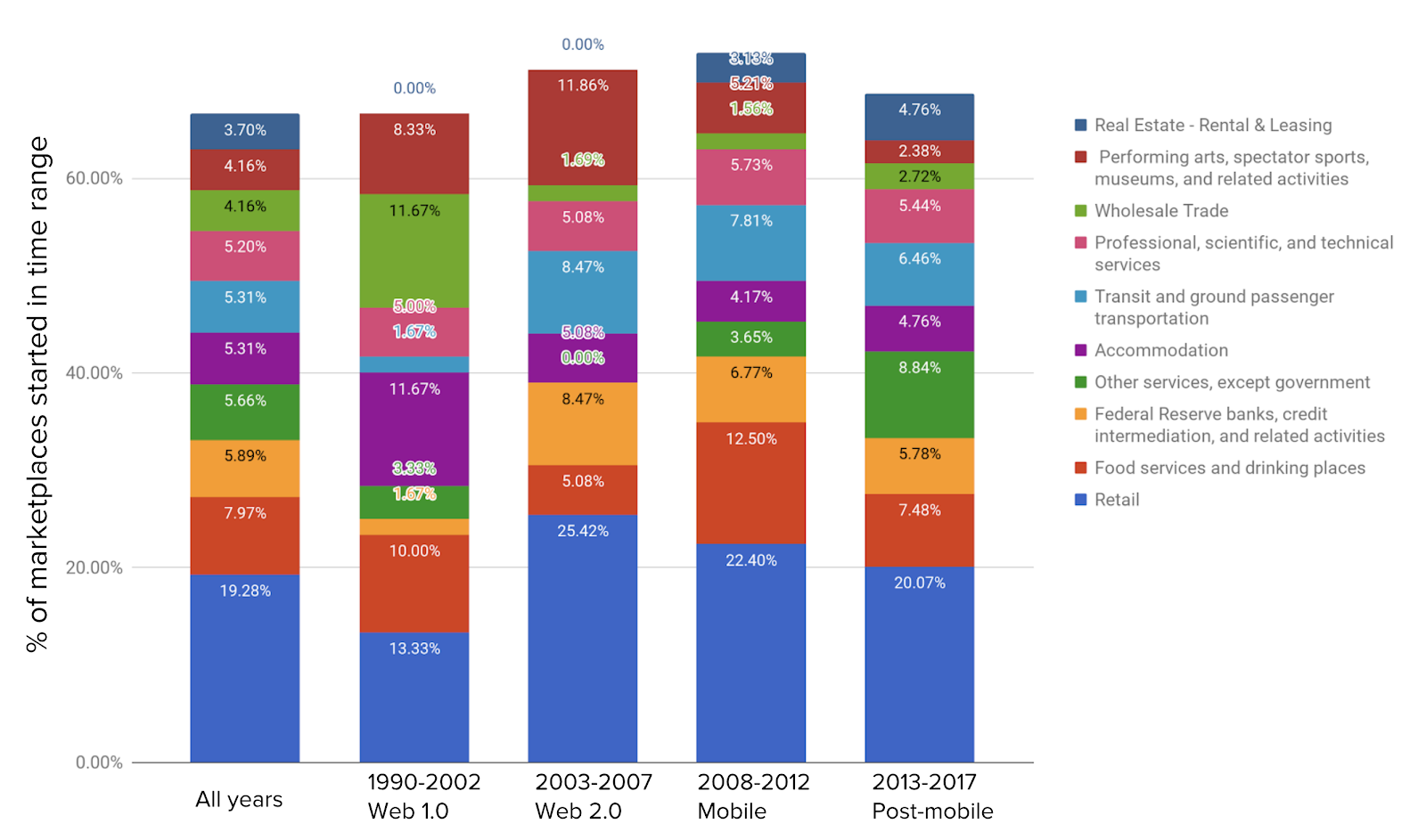

The below graph shows what types of marketplaces were started by time period. While retail marketplaces were the most popular marketplace categories in each time period, the #2 and #3 categories in each period change as entrepreneurs take advantage of new buyer markets that become accessible by these new platforms.

Before 2003, the most popular marketplace categories for entrepreneurs were use cases that took advantage of the web’s global reach: retail and accommodations (hotels). The largest marketplaces today are retail and accommodations marketplaces started in this period (Amazon, Alibaba, Booking.com, eBay) that expanded the addressable market for retailers and hotel companies.

In the mobile period (2008–2012) the most popular categories other than retail were food and ground transportation, two categories of marketplaces that are highly local and require the aggregation of buyers within each city. Uber, Didi and Meituan, the most valuable companies started in this period dominant these categories.

B2B marketplaces are an untapped opportunity

One category of marketplace that stands out in this chart is wholesale trade, which tied for the 3rd most popular category in the Web 1.0 period and included such companies as PaperExchange, Supply Chain Connect, and VerticalNet. With the exception of Alibaba (founded in 1999 as a B2B marketplace) none of the wholesale trade marketplaces started in this period have become large enduring, businesses (Elance, founded in 1999 and now UpWork, is classified as “Professional services”).

In 1999, these companies may have had large addressable markets, but not enough of the decision makers at those business were on the internet and ready to make a purchase. eBay only had 1 million buyers in 1999 and each of these B2B marketplaces would have a much smaller online addressable market.

In the last 16 years, this has changed. Since 2002, the number of global internet users has increased by almost 10 times, from about 400 million to almost 4 billion (half the world’s population). US internet adoption is 89% and 77% of adults have a smartphone.

These trends have driven a massive increase in B2B eCommerce spend. In 2018, Forrester predicts almost $1 trillion will be spent by US businesses on supplier websites (double the size of the consumer eCommerce market).

Much of this spend is by larger companies, but one of the most interesting opportunities for marketplaces will be in more fragmented SMB markets. Since 2002 there are 50% more small businesses in the US and more individuals are now running their own part-time businesses.

Despite these developments, less than 3% of marketplaces founded from 2013–2017 were connecting businesses with other businesses.

The demand from businesses is clearly there: Amazon launched it’s B2B-focused marketplace in 2015 to tackle this market and by January 2018 had already passed $1 billion in revenue with 400,000 business buyers and 45,000 sellers. Auto1Group connects the 1.5m car dealers worldwide and generated over $1.5 billion in GMV in 2016. Witmart and Upwork connect hundreds of thousands of contractors to hundreds of thousands of businesses that need contract, trademark, design, development, or hundreds of other tasks.

As entrepreneurs, we’re excited by the opportunity to build great products for under-served businesses in huge markets. Over the next 5 years we predict other entrepreneurs will start B2B marketplaces as well, perhaps reimagining some of the ideas that didn’t work 20 years ago.

“There are no bad ideas. There are only early ideas” — Marc Andreessen

Footnotes

- We only featured marketplaces where we had data on the number of buyers, suppliers, and revenue. Notable marketplaces missing from this analysis are Craiglist ($700m+ in revenue) and eBay (Almost $10bn in 2017 revenue) which both have millions of monthly sellers and would therefore increase the correlation between the number of suppliers and revenue.

- If you know of any that we are missing, please get in touch (marketplaces at elichait.com)

- Of the 9 marketplaces with $1bn+ of revenue, 6 have more than 1 million suppliers and 3 have less than 1 million suppliers.