The problem with trusting experience over expertise (a story about design thinking, astronauts…

The problem with trusting experience over expertise (a story about design thinking, astronauts, Formula 1 pundits and Brexit)

I was particularly struck by Khoi Vinh’s point about architecture critics.

Consider Michael Kimmelman, architecture critic at The New York Times. He nearly won a Pulitzer for his incisive writing which puts architecture in context, gives it meaning and makes it more relevant for countless people.

Now imagine if Kimmelman were a practicing architect. Imagine that he has projects all over the world and is working on a huge high rise in downtown Manhattan at the same time as he files his bylines at The Times. That would undoubtedly and profoundly change the way we think about what he has to say about architecture.

There is a wider point too about how the media — and society in general — has gradually drifted away from listening to these types of expert figures, who can provide context and meaning. Instead, we increasingly prefer to listen to practitioners — those who have experienced the thing they are talking about — no matter how much they actually know about it.

We liked them, these serious people with their heads in books and their eyes on planets. They could talk with authority about any constellation.

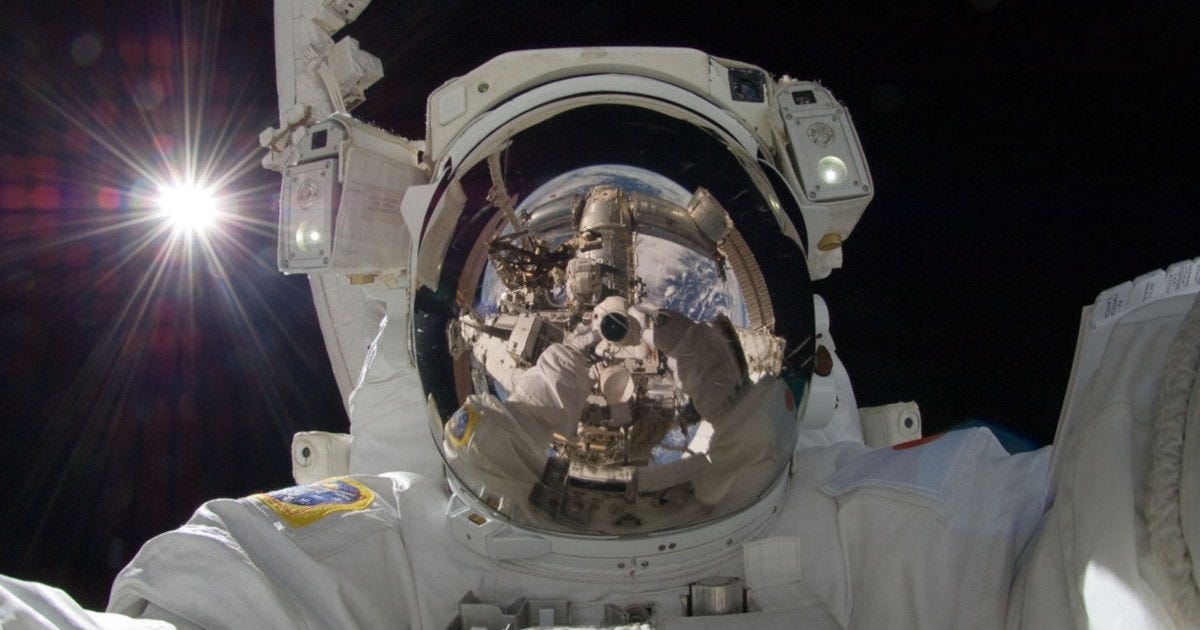

But today the broadcasters would rather go to the astronaut who has been on the moon, than the astronomer who “only” knew about it.

I can think of a shift within my lifetime in sports broadcasting too. When I was a child in the late 1990s, the Formula 1 pundits were respected journalist figures — even on ITV. People like Tony Jardine and Simon Taylor. They were rather bookish, but they provided historical context, acted as neutral observers, saw the bigger picture and communicated it.

Over time, such figures were slowly replaced with ageing ex-drivers. Again on ITV, the expertise didn’t always shine through. (Nor did the grasp of the English language.) The punditry became flat; the viewers became less enlightened. But there was a celebrity on the telly.

It has now reached the point where journalists are almost completely pushed out of the equation. With F1 punditry today (at least on certain channels), it feels like we only learn about how much better the sport was back in the good old days of the 1990s, when those very pundits happened to be driving. I know other sports have undergone a similar shift.

Jeremy Vine seems to approve of the marginalisation of the astronomers. But the astronauts, the F1 drivers and the architects bring their own biases to the table, and give us a more limited perspective.

When Michael Gove, in the run-up to the European Union referendum, said that people have had enough of experts, he was probably right. But it is dangerous to embrace that as a good thing — as our experience with Brexit is demonstrating.