What Do Bees Argue About?

What Do Bees Argue About?

A hive full of honey bees busily working away might seem like the epitome of harmony. After all, most of the workers are siblings working together to raise new brothers and sisters. However, even this family has conflicts now and then. Their arguments may actually be similar to the ones you have at the dinner table, but unlike your family feuds, they can be explained, at least partially, with genetics.

You may know that humans have two different sex chromosomes: X and Y. Bees, on the other hand, have no Y. By this genetic quirk, female bees have XX chromosomes, but males have only X. As each male inherits his single X chromosome from his mother, the queen, this makes him technically fatherless. Each female, a either worker or a queen, inherits one X from her mother and one from her father, as humans do. The upshot of this is that mating is actually completely unnecessary to produce males; a female bee can do it all by herself. This genetic arrangement can sometimes lead to different interests and conflicts between the inhabitants of a bee colony.

Treason and intrigue

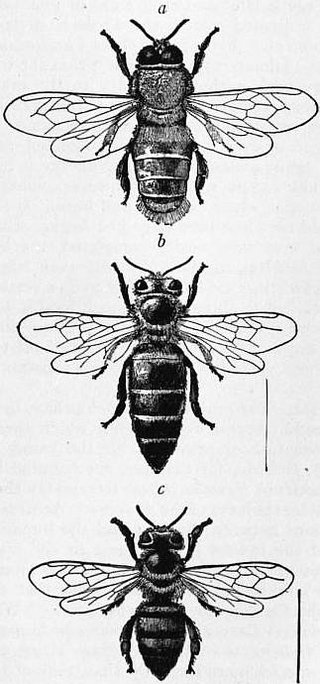

The problem starts during the queen bee’s nuptial flight. This is when a new queen emerges from the nest to mate. She may mate with several different males before settling down to spend the rest of her life producing eggs. Most of her offspring will be workers, which are all female, a few will be males, called drones, and the rest will be new queens.

The workers are the ones who make the honey and honeycomb, take care of the young bee larvae, and generally keep everything running smoothly. They’re quite happy to do this instead of raising their own offspring, because they’re sometimes actually more closely related to each other than they would be to their own potential offspring. This is due to the sex chromosome arrangement described above, and occurs when the workers are full sisters i.e. they share the same two parents. Workers who are full sisters are happy to only raise more siblings, but workers with different fathers may prefer to have their own offspring than put all their effort into raising half-siblings. This doesn’t sit well with the queen, who wants all the help she can get to raise her offspring. Normally worker reproduction is suppressed by pheromones produced by the queen, but sometimes this doesn’t work. If the workers figure out that they’re not more closely related to each other than to their own potential offspring, defection can occur. The workers may discover this via chemicals that they produce, which could be exchanged during mutual feeding or grooming.

Although workers are unable to mate — remember that it isn’t necessary to produce males — they are capable of laying unfertilised male eggs. The workers will lay their own eggs and raise sons, at least, if other workers don’t find and eat the eggs first. Although this is rare in normal colonies with a queen, it has been suggested these “anarchistic” workers have some way of preventing the usual reproductive policing and are able to get away with laying their own eggs.

Sibling rivalry

Workers will also begin laying their own eggs if the queen dies. This can then turn into worker-worker conflict, as some workers will eat the eggs of fellow workers in order to save more resources for their own offspring. The situation can then break down further if no new queen appears, with many workers partaking in egg laying and the end of worker-worker policing. This may be to give the colony one last chance to produce males that could go on to mate with a queen from another colony and therefore keep the genetic line going.

There are other opportunities for worker disagreements that aren’t related to genetics. When looking for food or a place to build a new nest, a few scouts venture out and report back with their findings. The scouts advertise their chosen food or nest site by dancing for the rest of the colony. The more vigorous the dancing, the better the site. In the case of house-hunting, they attempt to reach a consensus on the best possible site, so the whole colony can then safely make their way to their new home. Scouts dancing for one potential site may try to prevent other scouts from dancing for a rival site. They do this by vibrating their wings and headbutting each other, and it usually takes a few headbutts to persuade the other scout to stop dancing. This conflict does have a good purpose, though. It increases the chance that one particular site will be chosen by more scouts, and therefore prevents deadlocking when choosing between equally good nest sites.

Civil war

At a certain point in the colony’s life, the queen will produce eggs that will go on to become new queens. The eggs are the same as those that go on to become workers, but they are deposited in special queen cells in the honeycomb, which are larger than the ones that house worker larvae. The new larvae are given special food and care by the workers, which prompts them to grow into new queens. Similar to the way workers prefer to raise full siblings, workers also prefer to raise new queens that have the same father as themselves. Further conflict then arises when more queens are produced than are needed. This can lead to lethal competition between the new queens, either occurring when a newly emerged queen assassinates her still developing rivals in their cells, or through hand-to-hand combat. Sadly, this is usually the only way this conflict is resolved. When the colony is finally large enough, it will “reproduce” by fission, and the old queen will leave the nest with roughly half of the workers, while the new queen stays behind with the rest.

It turns out that bees argue about similar things things to us: children, relationships, food, and homes. However, the similarities seem to end there. Eating our sibling’s offspring and killing our sisters probably aren’t good ways of resolving our problems. On the other hand, the ways that bees and other social insects make decisions and cooperate with each other (as they do most of the time) could be a rich source of guidance for how to operate our own communities.