Understanding Compilers — For Humans (Version 2)

Introduction

What a Compiler is

What you may call a programming language is really just software, called a compiler, that reads a text file, processes it a lot, and generates binary. The language part of a compiler is just what the style of text it is processing. Since a computer can only read 1s and 0s, and humans write better Rust than they do binary, compilers were made to turn that human-readable text into computer-readable machine code

A compiler can be any program that translates one text into another. For example, here is a compiler written in Rust that turns 0s into 1s, and 1s into 0s:

What a Compiler Does

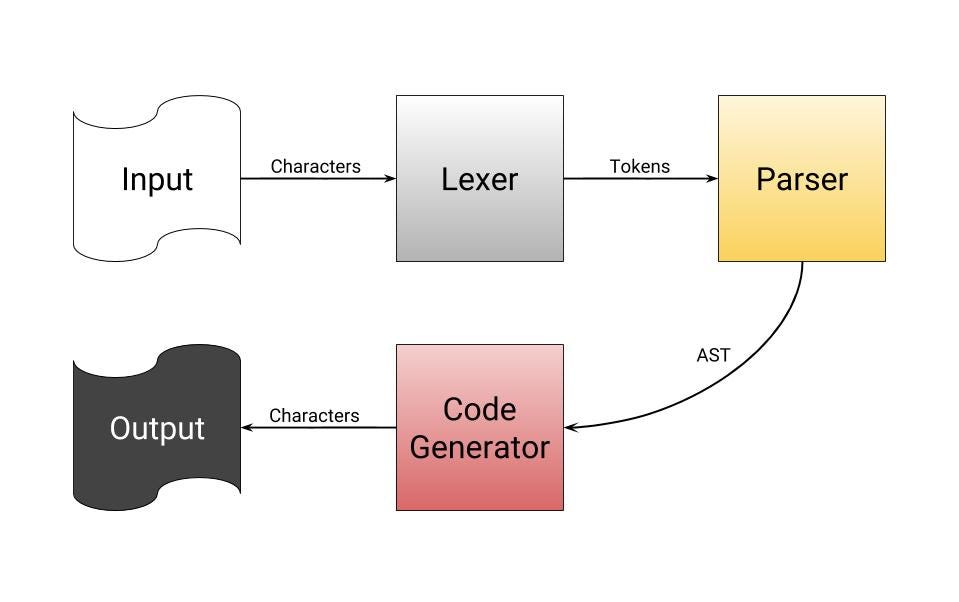

In short, compilers take source code and produce binary. Since it would be pretty complicated to go straight from complex, human readable code to ones and zeros, compilers have several steps of processing to do before their programs are runnable:

- Reads the individual characters of the source code you give it.

- Sorts the characters into words, numbers, symbols, and operators.

- Takes the sorted characters and determines the operations they are trying to perform by matching them against patterns, and making a tree of the operations.

- Iterates over every operation in the tree made in the last step, and generates the equivalent binary.

While I say the compiler immediately goes from a tree of operations to binary, it actually generates assembly code, which is then assembled/compiled into binary. Assembly is like a higher-level, human-readable binary. Read more about what assembly is here.

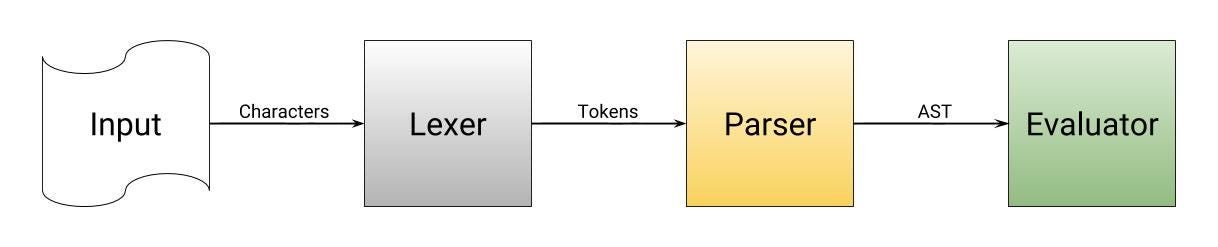

What an Interpreter is

Interpreters are much like compilers in that they read a language and process it. Though, interpreters skip code generation and execute the AST just-in-time. The biggest advantage to interpreters is the time it takes to start running your program during debug. A compiler may take anywhere from a second to several minutes to compile a program, while an interpreter begins running immediately, with no compilation. The biggest downside to an interpreter is that it requires to be installed on the user’s computer before the program can be executed.

This article refers mostly to compilers, but it should be clear the differences between them and how compilers relate.

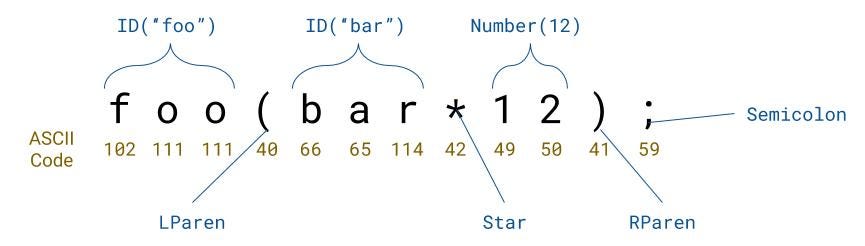

1. Lexical Analysis

The first step is to split the input up character by character. This step is called lexical analysis, or tokenization. The major idea is that we group characters together to form our words, identifiers, symbols, and more. Lexical analysis mostly does not deal with anything logical like solving 2+2 — it would just say that there are three tokens: a number: 2, a plus sign, and then another number: 2.

Let’s say you were lexing a string like 12+3: it would read the characters 1, 2, +, and 3. We have the separate characters but we must group them together; one of the major tasks of the tokenizer. For example, we got 1 and 2 as individual letters, but we need to put them together and parse them as a single integer. The + would also need to be recognized as a plus sign, and not its literal character value — the character code 43.

If you can see code and make more meaning of it that way, then the following Rust tokenizer can group digits into 32-bit integers, and plus signs as the Token value Plus.

You can click the “Run” button at the top left corner of the Rust Playground to compile and execute the code in your browser.

In a compiler for a programming language, the lexer may need to have several different types of tokens. For example: symbols, numbers, identifiers, strings, operators, etc. It is entirely dependent on the language itself to know what kind of individual tokens you would need to extract from the source code.

2. Parsing

The parser is truly the heart of the syntax. The parser takes the tokens generated by the lexer, attempts to see if they’re in certain patterns, then associates those patterns with expressions like calling functions, recalling variables, or math operations. The parser is what literally defines the syntax of the language.

The difference between saying int a = 3 and a: int = 3 is in the parser. The parser is what makes the decision of how syntax is supposed to look. It ensures that parentheses and curly braces are balanced, that every statement ends with a semicolon, and that every function has a name. The parser knows when things aren’t in the correct order when tokens don’t fit the expected pattern.

There are several different types of parsers that you can write. One of the most common is a top-down, recursive-descent parser. Recursive-descent parsing is one of the simplest to use and understand. All of the parser examples I created are recursive-descent based.

The syntax a parser parses can be outlined using a grammar. A grammar like EBNF can describe a parser for simple math operations like 12+3:

Remember that the grammar file is not the parser, but it is rather an outline of what the parser does. You build a parser around a grammar like this one. It is to be consumed by humans and is simpler to read and understand than looking directly at the code of the parser.

The parser for that grammar would be the expr parser, since it is the top-level item that basically everything is related to. The only valid input would have to be any number, plus or minus, any number. expr expects an additive_expr, which is where the major addition and subtraction appears. additive_expr first expects a term (a number), then plus or minus, another term.

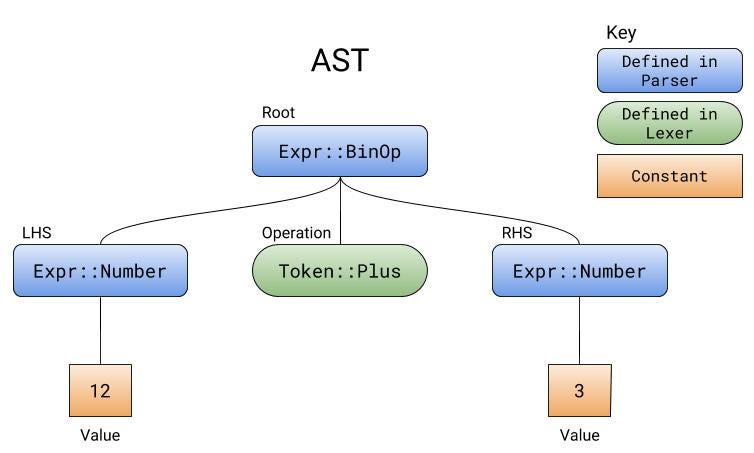

The tree that a parser generates while parsing is called the abstract syntax tree, or AST. The ast contains all of the operations. The parser does not calculate the operations, it just collects them in their correct order.

I added onto our lexer code from before so that it matches our grammar and can generate ASTs like the diagram. I marked the beginning and end of the new parser code with the comments // BEGIN PARSER // and // END PARSER //.

We can actually go much further. Say we want to support inputs that are just numbers without operations, or adding multiplication and division, or even adding precedence. This is all possible with a quick change of the grammar file, and an adjustment to reflect it inside of our parser code.

if(net>0.0)total+=net*(1.0+tax/100.0);", the scanner composes a sequence of tokens, and categorizes each of them, e.g. as identifier, reserved word, number literal, or operator. The latter sequence is transformed by the parser into a syntax tree, which is then treated by the remaining compiler phases. The scanner and parser handles the regular and properly context-free parts of the grammar for C, respectively. Credit: Jochen Burghardt. Original.3. Generating Code

The code generator takes an AST and emits the equivalent in code or assembly. The code generator must iterate through every single item in the AST in a recursive descent order — much like how a parser works — and then emit the equivalent, but in code.

If you open the above link, you can see the assembly produced by the example code on the left. Lines 3 and 4 of the assembly code show how the compiler generated the code for the constants when it encountered them in the AST.

The Godbolt Compiler Explorer is an excellent tool and allows you to write code in a high level programming language and see it’s generated assembly code. You can fool around with this and see what kind of code should be made, but don’t forget to add the optimization flag to your language’s compiler to see just how smart it is. (-O for Rust)

If you are interested in how a compiler saves a local variable to memory in ASM, this article (section “Code Generation”) explains the stack in thorough detail. Most times, advanced compilers will allocate memory for variables on the heap and store them there, instead of on the stack, when the variables are not local. You can read more about storing variables in this StackOverflow answer.

Since assembly is an entirely different, complicated subject, I won’t talk much more about it specifically. I just want to stress the importance and work of the code generator. Furthermore, a code generator can produce more than just assembly. The Haxe compiler has a backend that can generate over six different programming languages; including C++, Java, and Python.

Backend refers to a compiler’s code generator or evaluator; therefore, the front end is the lexer and parser. There is also a middle end, which mostly has to do with optimizations and IRs explained later in this section. The back end is mostly unrelated to the front end, and only cares about the AST it receives. This means one could reuse the same backend for several different front ends or languages. This is the case with the notorious GNU Compiler Collection.

I couldn’t have a better example of a code generator than my C compiler’s backend; you can find it here.

After the assembly has been produced, it would be written to a new assembly file (.s or .asm). That file would then be passed through an assembler, which is a compiler for assembly, and would generate the equivalent in binary. The binary code would then be written to a new file called an object file (.o).

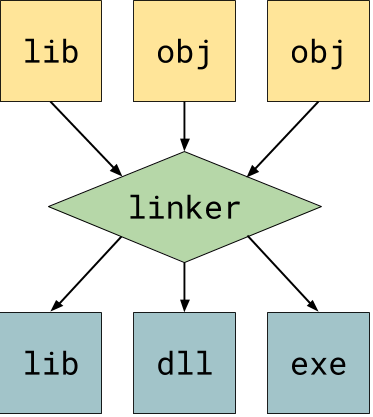

Object files are machine code but they are not executable. For them to become executable, the object files would need to be linked together. The linker takes this general machine code and makes it an executable, a shared library, or a static library. More about linkers here.

Linkers are utility programs that vary based on operating systems. A single, third-party linker should be able to compile the object code your backend generates. There should be no need to create your own linker when making a compiler.

A compiler may have an intermediate representation, or IR. An IR is about representing the original instructions losslessly for optimizations or translation to another language. An IR is not the original source code; the IR is a lossless simplification for the sake of finding potential optimizations in the code. Loop unrolling and vectorization are done using the IR. More examples of IR-related optimizations can be found in this PDF.

Conclusion

When you understand compilers, you can work more efficiently with your programming languages. Maybe someday you would be interested in making your own programming language? I hope this helped you.