Arvind Gupta’s Jiu Jitsu Makes Biotech Move at Silicon Valley Speed

The week I spend at IndieBio is packed with seminars, panels, deep dives, and a constant trickle of visitors. On Monday, Gupta teaches a class in structuring a venture deal. One of his insights: startups should already be bringing in loans known as bridge notes from VCs even if they’re months from ready for equity deals. “Rule One: Don’t die,” he declares. “Rule Two: Get the terms you want. But if that doesn’t work, refer to Rule One.” Every day, Gupta drags a startup upstairs for a deep dive into its science, or for a session to build a “Reverse Income Statement” — a P&L imagining they’ve hit $100 million in revenue, breaking out all likely costs, to calculate future margins. Four venture capitalists stop by, as do three IndieBio graduates willing to consult with a startup in their market.

Fridays are tonally bipolar, by design. The morning begins with Gupta leading “Killer of the Week,” where a small trophy is passed to the startup that has made the most progress in the past seven days. Then the day finishes with “Journey Talks,” where three founders must stand before their peers and tell their personal story, complete with photos of their childhoods. This baring of their soul creates bonding among the class, forcing the founders to be in touch with their emotional core.

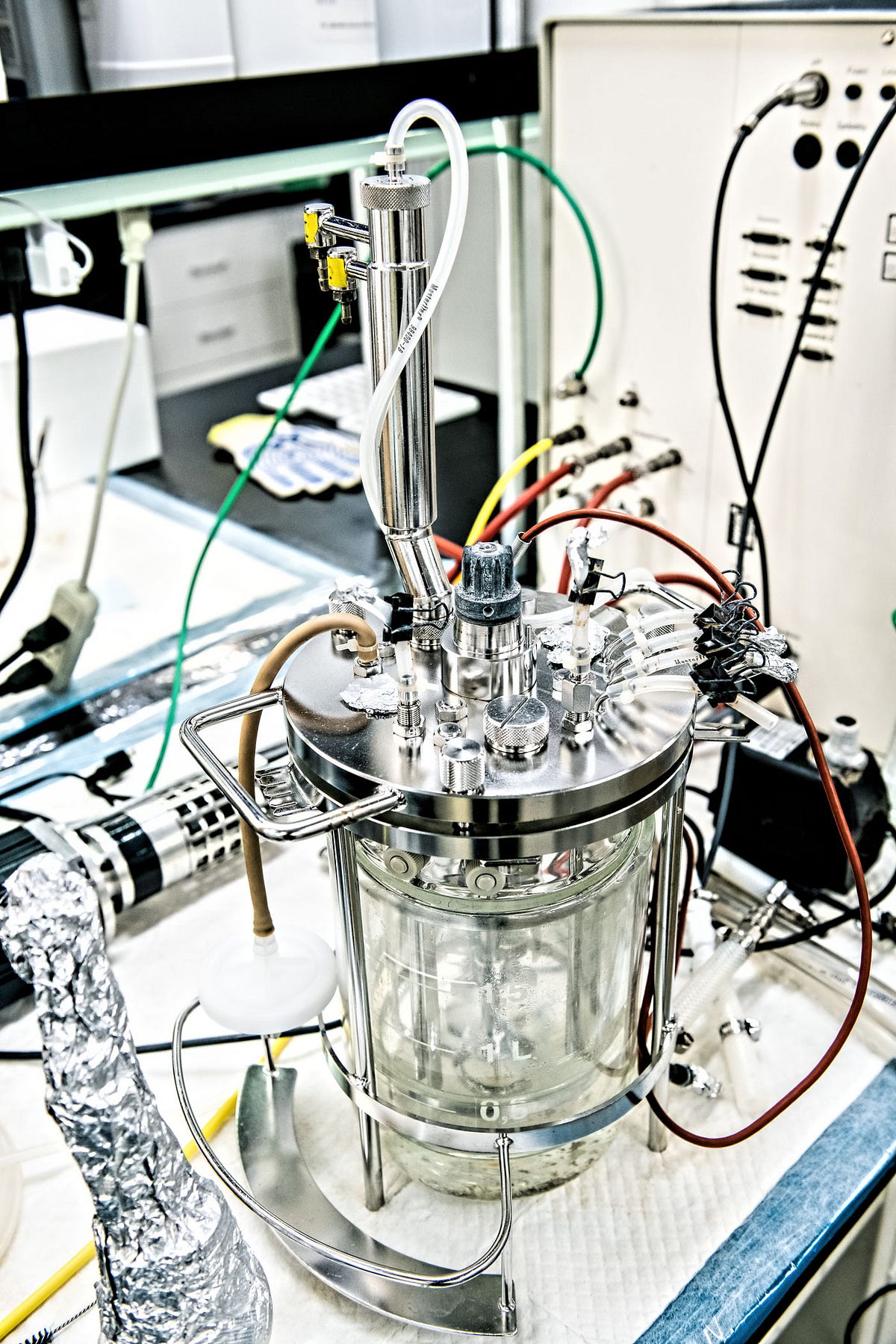

Gupta oversees it all, both as grandmaster and continuous participant. What becomes immediately clear is that, even though he didn’t spend a decade in venture capital or a decade as a bench scientist, he has learned the equivalent in three years on this job, by shepherding 81 startups through this process. As we tour the lab, he teaches me the thermal cycling process in a polymerase chain reaction machine used in gene manipulation. In a deep-dive hour with a gene-therapy startup, Serenity Bioworks, he brings to bear his past experience with another startup, Prellis, which uses little sacs called liposomes to deliver drugs in the body. Making the most of the hour, Gupta helps Serenity’s founders frame their story to investors, recommends a business model, and pushes them to tweak one of their experiments, which they will do the next day.

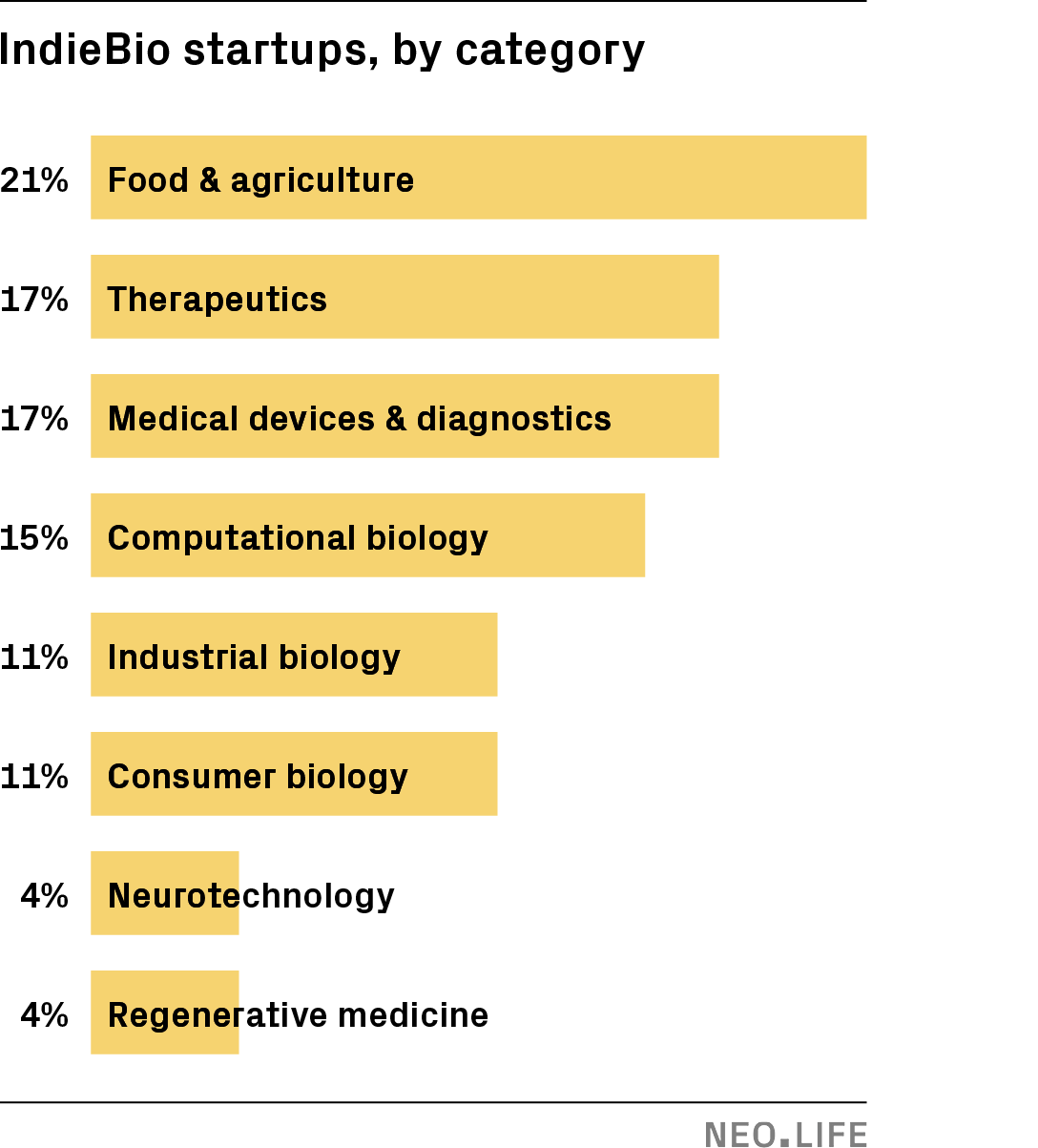

Gupta doesn’t have to play catch-up. In fact it’s more like everyone has to catch up to him. His counsel is constant and he asks the startups strategic questions so fast they barely have time to answer him. Having had a dozen cellular agriculture companies come through IndieBio, Gupta draws on their experience to advise companies in this class that are working on bioengineered pork sausage and fish feed. In the same way, Gupta and the team at IndieBio have gained wide experience across gene delivery, stem cells, the microbiome, disease prediction, medical devices, brain-machine tech, and age-reversing mechanisms.

Startups have constant access to a staff with as much variety as the gang in Ocean’s Eleven. Taylor Sittler is a physician and co-founder of Color Genomics. Jun Axup is a biochemist from Scripps; she went through IndieBio in its second class with the startup MYi Diagnostics. Alex Kopelyan has a PharmD degree and is an expert on business models. Parikshit Sharma is the quant, an analyst and data scientist. Maya Lockwood programs the leadership track with Kopelyan; she’s trusted to make sure the entrepreneurs don’t lose touch with their soul in the process.

Young computer engineers are expected to stay up all night and have the code by morning. They’re well-prepared for the high-speed, build-and-test cycles of startups. That’s less true for molecular biologists, MDs, and lab scientists, who have learned the slow and careful method of academia, where, you might have a great idea what to do next, but first you must write a grant application. A year later, you receive the grant — and then you have to do exactly what you wrote in the grant. If you had a better idea in the meantime, you might be able to jam it in. Writing papers for publication is critical to the process, but time consuming, and often feels like giving away the discovery, both to nobody and to everybody.

“I really care that what we do here, in these 16 weeks, adds real value to the companies,” Gupta says. “It’s possible what we do doesn’t matter — that we’re just really good at selecting the best applicants, with the best science and the best co-founders. And they would do just as well without our program.” To me, this is a sort of straw man self-interrogation. It’s plainly obvious the startup founders need the scaffolding, and that if the accelerator program didn’t exist, few would have left academia, where life was slow, but safe. It simply would have been too risky, the chasm too far.

More than that, it’s likely no investor would gamble on them, either. Until IndieBio and its kin emerged, biotech innovation was only getting more expensive. A typical Series A biotech investment to do preclinical discovery might be $20 million, in milestone payments, with $5 million up front. VCs need to feel fairly confident to bite, which filters out thousands of scientific possibilities that don’t meet their standard. IndieBio, meanwhile, can take on science that is a little more risky, while spending only $250,000 and four months. IndieBio can fund 20 companies for every one that Sand Hill Road funds. This widens the funnel and provides career paths for postdoctoral scientists that didn’t exist before.

Another way to think about this is from a chronological perspective. IndieBio is able to test the commercial potential of certain threads of scientific inquiry roughly three or four years before they would be ready for traditional biotech investment. “A year ago, at Stanford, when we discovered our method was working across a variety of cancers … we were so excited that I didn’t even want to publish a paper, I wanted to file a patent,” says Xiyan Li, cofounder of Filtricine, which intends to treat cancer with dialysis. “But we drafted a protocol to continue our research. There were all kinds of regulations and funding issues. It was moving too slow. Even if we had waited for the grant, it would have been at least a couple years to test it in mouse models.” Frustrated, he and his team applied to IndieBio. Already, just three weeks into the program, they are performing those very tests on mice.

Subhadeep Das, co-founder of the startup Convalesce, which transplants stem cells into the brain, tells a similar story. He finished his Ph.D. in Mumbai just a year ago, and his co-founder, Amrutraj Zade, is a year from finishing his. “Even though we have a patent, if we stayed in academia, the science alone would take three years before we could think of approaching biotech,” he estimates. He had one meeting with a pharmaceutical CEO last spring. “He said, ‘Whoa, you’re starting with the brain?’ He wanted us to start with something smaller, below the neck. They wanted us to go slower, not faster.”

Gupta is careful to clarify that IndieBio’s sprints are only for the early phases of biotech innovation. When it comes to FDA approval of safety and efficacy, those phases will go at normal speed. “I will run towards regulation rather than away from it,” he says.