What do you mean ‘we need more time’??

Ready? Here we go.

Task Breakdown

- Confirm the requirements. Make sure everyone agrees on the exact color and which walls should get painted, for example. (5 minutes)

- Research how to paint a room if you don’t already know. You’ll probably learn some important details about primers and how long to wait between coats, for example. Re-confirm any ambiguities with stakeholders — maybe you just learned that paint comes in different glosses. (15 minutes)

- Make a shopping list and acquire your materials, e.g. paint, rollers, paint trays, brushes, drop cloths, etc. (2 hours)

- “Prototype” your paint job in a section of the room to make sure the original color isn’t showing through. This could save you a lot of time if, for example, you didn’t think you needed a primer but you do. (10 minutes painting, 2 hour dry time between coats)

- Remove everything on or near the walls, like paintings, curtains, and light switch covers. Push furniture away from the walls, and cover furniture and floors if painting the ceilings. (30 minutes)

- Wash your walls and inspect them for any cracked or peeling areas. You’ll want to patch and sand down any of these before you start painting. (1 hour)

- Secure drop cloths or equivalent, starting at the baseboards so you don’t drip paint on the baseboards or floor. Tape off the edges of all the things you don’t want painted, like windows, doors, and cabinets. (1 hour)

- Prime the room. (1.5 hours)

- Allow the primer to dry. (30 minutes if you start painting in the same spot you started priming)

- Wash primer off any equipment you’ll reuse for painting. (20 minutes, but this can be overlapped with drying time)

- Apply the paint. (2 hours)

- Clean up. (30 minutes)

OK, let’s take a pause from painting for a minute and step back into the world of software engineering process to note some similarities.

Room Painting and Software Parallels

Some of these steps may seem silly. Double check the color? But failing to nail down all details of the spec before implementing is a very common mistake, and you might spend a lot of time making something nobody wants (see teapot). The tiniest difference in the spec (“Oh, you wanted waterproof paint in a different gloss, and only on one wall? Well [a-z]{4}.”) can be very costly to fix afterwards.

Without research or a prototype, you could spend a lot of time going down rabbit holes. With a bit of digging, you might find that there’s already a framework that does exactly what you want. A basic prototype might then reveal that the framework documentation was lying or doesn’t cover one crucial scenario, and it doesn’t actually do what you want, and you’ll have to do it yourself after all! If your prototype was very cheap, you just saved yourself the wasted work of integrating the framework into your production system.

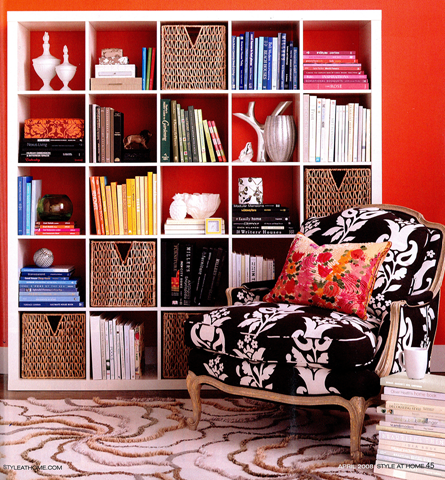

Then, if you don’t break the tasks down into small enough pieces, you might fail to notice some very important points. For example, if you had forgotten about moving the furniture, you might not have had a second person on hand to move that giant Expedit bookshelf. The more you break things down, the more you realize you overlooked.

More importantly, the biggest factor in the accuracy of your estimate is whether or not you’ve done something like this before. Even with extensive research, it’s hard to know how many coats you’ll need in order to paint over that particular color, what your personal painting speed is, or how the humidity in your area affects drying time. In fact, if you’ve done this exact project before, you can skip steps 1 through 4 altogether. But if you haven’t, you were probably repeatedly surprised by steps you’d forgotten to account for, and the prep work will give you a far more accurate estimate than your initial guess. And it does mean that you won’t have a real estimate until you’re done with step 4. Anything you say before that will be a wild guess that you’ll probably have cause to regret later, so it’s safest to say “I don’t know but I can probably tell you in a few days” until then.

OK, back to painting. We’ve costed it out and it’s about 12 hours. Are we done?

Well…the paint and prime steps have way less detail than the other tasks. Face it, you still don’t actually know how that part will be done, so your estimates are wild guesses. Recursively applying the principles above, let’s break it down more.

Break Down All Ambiguities

- Prepare the paint by mixing it all into a large bucket. Pour some of it into a paint tray. (15 minutes)

- Paint edges with a brush, getting into corners and right up to ceilings and doors without coloring anything that isn’t supposed to be yellow. If you do 5 feet of edging in 3 minutes and there’s 210 feet of edging in the room, that’s just over 2 hours. Add another 20 minutes for going up and down a ladder and scooting it around. And if you don’t have a ladder, you’d better add it to the shopping list. (Call the whole thing 2.5 hours)

- With one dip of a roller, you can probably do a floor-to-ceiling, roller-width section of wall in a couple of passes, so you can probably do a 5 ft wide section in about 10 minutes. (1.5 hours)

- Your “prototype” will tell you how many coats of paint you’ll need. This could significantly lengthen your paint time, so you should account for that as well. (Multiply by the number of coats, and factor in the drying time).

You’ll also realize that priming is not very different than painting. So double this estimate for priming.

All tallied up, assuming one coat, that’s about 15 hours for the whole shebang. Phew, that’s a lot longer than we initially thought! And just to be safe, let’s leave a bit of buffer time for unexpected setbacks, like needing to jerry-rig a strainer to remove chunks from your paint. So we’ll make it an even 17 hours. Final answer, let’s get painting, right?

Nope, still not there yet!

External Factors

Yeah, you’ve estimated how long it’ll take to paint the room. But that’s not what anyone wants to know. They want to know how long it’ll be before the room is painted. It’s a subtle but important distinction. When I ask about a bug, it’s nice to hear that you can code up a fix in an hour, but what I actually needed to know is that you won’t get around to it until next week, so it’ll be done in a week and an hour! The fact that I technically only asked how long the fix would take is something only an engineer would bother pointing out.

-_-

So what are we still missing in this estimate? Bathroom and meal breaks, random interruptions, and competing priorities. Your work could be delayed by all kinds of incidents, expected and unexpected. Maybe you had to stop early because it’s laundry day, or some emergency came up. How can you even factor in that kind of unpredictability?

The answer is lots of buffering, based on past experience. You can track a multiplier for your estimates by logging how long it actually took you to do each task and comparing your initial schedule with the real time elapsed for the project. Since every project tends to be quite different, you won’t be able to reach fantastic accuracy by refining individual task estimates over time. But a multiplier applied to the whole project will account for everything from your natural optimism, to the fact that you have more meetings than you realized, to the time you spend procrastinating by surfing the internet.

I won’t get into greater detail here, because there is already a terrific article on this subject by Joel Spolsky called Evidence Based Scheduling. While his method may sound time-intensive, tracking time sheets for just a couple of projects can help refine your estimates a lot. Like all skills worth improving, this one will take time and effort to hone.

Intercepting Bad Estimates

The above is all fine and dandy if you’re asked to give estimates. But as a software engineer, you’re often handed a schedule along with your project. Maybe the deadline was set by marketing because they want it to be available in time for Christmas, or by a manager who needs a date to coordinate with other teams who have their own deadlines. Or maybe they haven’t given you a schedule, but you can tell from the gleam in their eyes that they have Certain Expectations. The important thing is, if you think the dates are unrealistic, you need to speak up.

Ideally, each engineer should each be able to estimate his or her part of the project from scratch, rather than anchoring on a schedule someone else has given. It can be easy to convince yourself that you can do a project in two weeks, or at least not question that number too much, if that’s how long your manager or tech lead says. Only when you sit down and do the real work of estimation will you find out how wrong it is.

It’s really important to actually do your estimation due diligence early and discuss any unrealistic deadlines. Remember — when you push back against a bad schedule, you are not a Debbie Downer fighting against a magical world where you ship the project by Christmas and everything is awesome. That world doesn’t exist. You simply prefer a world where everyone compromises on the date and feature set and then meets those goals, rather than a world where the deadline gets missed, or gets met by last-minute corner cutting and sacrifices in quality, with a generous side of reproach and finger-pointing. If your lead or PM really isn’t buying it, maybe point them to the article on Evidence Based Scheduling (really I can’t recommend it enough).

Yes, all this sounds like a lot of work. But I assure you, for any project sufficiently important, a more accurate schedule will save everyone a lot of grief. Hopefully, you now have more tools in your tool belt to create more accurate schedules for future projects!