Why You Can’t Stop Looking at Other People’s Screens

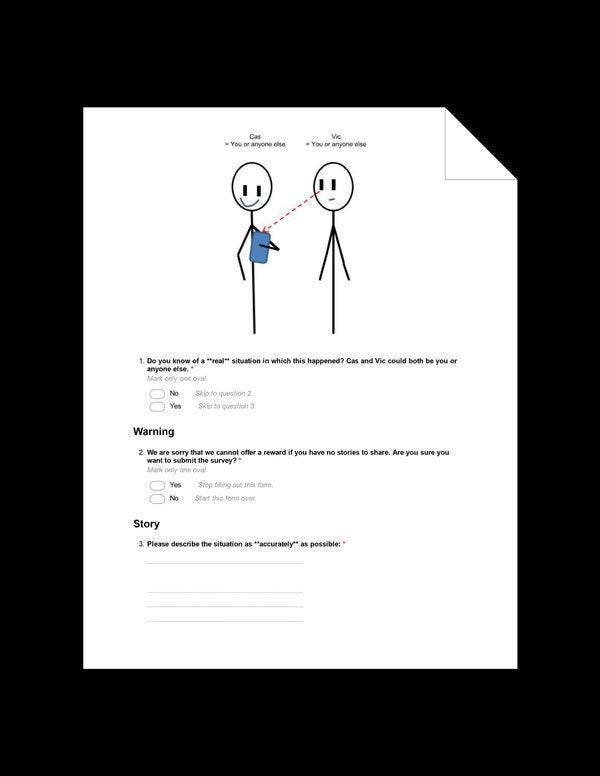

In a world in which other people’s screens are virtually impossible to ignore, there were “no detailed investigations of shoulder surfing incidents and their real-world implications,” wrote the researchers in Munich. So they distributed a survey, asking a range of questions about a hypothetical scenario in which a fictional character named “Vic” is looking at the mobile device of another fictional character named “Cas,” and Cas remains “not aware” of it.

Vic and Cas, who, disarmingly, “could both be you or anyone else” are shown as stick figures to help participants respond to prompts like: “Do you know of a **real** situation in which this happened?” and “What exactly could Vic see on the screen (e.g. text, pictures, passwords/PINs, maps, videos, apps, games, etc.)?”

The responses to the survey did not reveal a world of thieves and victims, exactly. In their analysis, the researchers suggested that “shoulder surfing was mostly casual and opportunistic.” It was “most common among strangers, in public transport, during commuting times, and involved a smartphone in almost all cases,” they said. Few participants indicated malicious intent when they admitted to acting like Vic and spying on Cas. “However,” the researchers wrote, “both users and observers expressed negative feelings in the respective situation, such as embarrassment and anger or guilt and unease.”

What did subjects see, on other people’s screens? Nearly half the time the answer was text. Then pictures, then games, then — in the shoulder surfing tradition — “credentials,” or passwords, more specifically. More specifically, in order of frequency, other people’s phones revealed: instant messaging, Facebook, email and news.

What did subjects “observe,” on other people’s screens? “Relationships / third persons,” most of all, but then interests and hobbies and “plans.” Why did they look at other people’s screens? “Curiosity” and “boredom” tied for first, with nothing else coming close.

Nobody really likes the idea that other people are looking at their screens. When they imagined being observed, survey participants reported negative feelings — that they felt they had been spied on, harassed, or that they were angry — in 37 cases, with just one respondent reporting “positive feelings.” (And “amused” that someone was watching.)

Other people also do not enjoy being asked about other people’s screens, in my experience, in part because they know what they’ve seen, and that they probably shouldn’t have seen it. (Fellow journalists seem somewhat less conflicted about catching a glimpse of a screen on the subway or a bus.) It’s a global phenomenon, of course, but stories abound in New York, the U.S. capital of other people’s screens. On the subway, and on the bus, other people’s screens join distinguished company: ads, the floor, the covers of books, and — a closer relation — accidental eye contact.

Other people’s screens on the subway were, until recently, glimpses of an archive: there was little access to cell service, or Wi-Fi. That was a more leisurely era, on other people’s screens; the “Candy Crush” years, the reading-in-apps years, the phone-as-book-or-magazine years, and the tiny television years. Other people’s screens found the fabled end-of-the-feed, at least for the duration of an underground commute.

Then came the signal, and with it everything else. In 2018, other people’s screens are habitually, frantically refreshed.

Other people’s screens are works in progress: they are tense and short texts with no context, typed and retyped, and then, for those underground, sent at the next stop; they are extraordinarily long messages, exchanges of lengths I was not aware were possible on a phone, from which one instantly turns away in shame after spotting the word “divorce;” they are selfies getting touched up, and then discarded; they are seemingly infinite group message chains full of religious affirmations; they are work emails with a lot of talk about clients, and the client, and our client, because the train is a place of work now, just like the office, just like the home.

Other people’s screens make recommendations, sort of. There is no “How are you enjoying that book?” with other people’s screens, only clues. Other people’s screens play more action movies than you might expect, and sometimes far more interesting TV, not that you can tell what’s going on, or what the show is even called. Other people’s screens make you aware that it is quite hard to Google a game when the only way you can describe is as a very pretty puzzle with lots of polygons that need to be matched or connected. Other people’s screens suggest that people text each other in an astounding variety of ways, but mostly in WhatsApp. Other people spend a lot of time trying to figure out what to listen to, on their screens.