Inside The Event Loop · The Factotum

Inside The Event Loop · The Factotum

In tech, most of the new features we pray are usually just a slightly different version of an old technology that people forgot about for a while and some smart guy revamped giving it a second youth.

This is what happened with asynchronous programming when JS and Python provided native support for it introducing two new keywords await

async, providing a better way to write asynchronous code that needs to wait for a promise, or future, to complete before executing the rest of the code. They are great, and they make the code more readable without having thousands of callbacks, like in Node, or weird hacks, like the yield in TornadoTransitioning from synchronous to asynchronous is not easy, you need some time to get your head around it, and most of the times people get lost because they don’t understand how these keywords were implemented and what makes their code asynchronous. So, let’s take a look at what’s going on under the hood when we use these asynchronous keywords.

Note: I’ll use Python for the examples, but all the example and concepts apply to any language or framework that supports asynchronous programming.

What’s Going on Under the Hood

All new (useful) things are born because of a real need, in this case, somebody’s must have asked himself: “Why do I need to block my process if a remote server is doing the work for me?”

Somebody might have suggested forking the main process into two, but that adds considerable overhead to the application. So, people started thinking how to solve this problem, and this thinking gave birth to some of the syscalls we have in Linux today: select, poll, and epoll. All of them work; similarly, they allow to register several file descriptors and let the code poll for any new events regarding those files, so you don’t need to block the process when something is happening in the background.

Let’s start with an example from real life. You want to send a letter to a friend, so you post a letter and wait for a reply. However, what do you do in the meanwhile? Wait in front of the mailbox until you get your friend’s letter? Or keep going with your life and check every morning if she replied? I bet you won’t spend days in front of the mailbox.

The same thing happens when you send data over the wire using a socket. You have two options wither stop your entire process until the server responds or let it do something that doesn’t require the server’s reply.

In the code below, the methods connect and send are blocking the process waiting for the server to accept the connection and send the data.

import socket

s = socket.socket(type=socket.SOCK_STREAM)

s.connect("example.com", 80) # block until the connection is estabilisheds.send(b"GET / HTTP/1.1\r\nHost: example.com\r\n\r\n")data = s.recv(1024) # block until it receives data from the serverprint(data)

time gives a good overview of what the process did: 0.07s user 0.02s system 26% cpu 0.312 total. This means that it spent 0.312s - 0.07s - 0.02s = 0.222s waiting for the server to respond. It could have done at least 20 more requests without affecting the total time!

Digging into the socket documentation, you can find the flag SOCK_NONBLOCK, a shortcut to set O_NONBLOCK when creating a new socket.

This prevents open from blocking for a “long time” to open the file. This is only meaningful for some kinds of files, usually devices such as serial ports; when it is not meaningful, it is harmless and ignored. Often, opening a port to a modem blocks until the modem reports carrier detection; if O_NONBLOCK is specified, open will return immediately without a carrier.

“open will return immediately”? It sounds like something we might use to make our code asynchronous. Let’s try it.

import socket

s = socket.socket(type=socket.SOCK_STREAM|socket.SOCK_NONBLOCK)

s.connect(("example.com", 80))It raises BlockingIOError: [Errno 115] Operation now in progress. Ouch! What does is it mean? That’s the error EINPROGRESS:

The socket is nonblocking and the connection cannot be completed immediately.

connect returns immediately even if the connection has not been completed because it was created using the non-blocking flag. The only thing we can do is calling it until it doesn’t raise an exception.

import socket

s = socket.socket(type=socket.SOCK_STREAM|socket.SOCK_NONBLOCK)

while True: try: s.connect(("example.com", 80))except BlockingIOError: continue

else: break

s.send(b"GET / HTTP/1.1\r\nHost: example.com\r\n\r\n")

This time it raises BlockingIOError: [Errno 11] Resource temporarily unavailable. Same exception class but different error code EAGAIN:

The socket is marked nonblocking and the requested operation would block.

and the error name suggest what the code should do: try again!

import socket

s = socket.socket(type=socket.SOCK_STREAM|socket.SOCK_NONBLOCK)

while True: try: s.connect(("example.com", 80))except BlockingIOError: continue

else: break

try: size = s.send(b"GET / HTTP/1.1\r\nHost: example.com\r\n\r\n") # we should check how many bytes were sent but this is not # production code

except BlockingIOError: pass

while True: try: data = s.recv(1024)

except BlockingIOError: continue

else: break

print(data)

Finally, it gets the server response ? This allows the code to do something while waiting for connect, send, and recv to finish, but let’s face it, the code is ugly as hell and adding any new request would make it unmaintainable.

The best way to improve it is using of one of the I/O multiplexing syscalls. I’ll use epoll as it’s the most performant and used in all modern event loop implementations.

The epoll API performs a similar task to poll(2): monitoring multiple file descriptors to see if I/O is possible on any of them.

When using asynchronous programming at a low level, the best way to organise the code is using a state machine, where each task has a state and a context where it can store any data it needs.

from enum import Enumfrom io import BytesIOimport socketfrom select import epoll, EPOLLOUT, EPOLLIN

class State(Enum): CONNECTING = 1 RECEIVING = 2 DONE = 3

def create_task(host): sock = socket.socket(type=socket.SOCK_STREAM) try: sock.connect((host, 80))

except BlockingIOError: pass

return { "host": host, "socket": sock, "state": State.CONNECTING, "data": None, }p = epoll()

tasks = {}# create the first task that will fetch example.com's home pagetask_example = create_task("example.com")tasks[task_example["socket"].fileno()] = task_example# create the second task that will fetch Wikipedia's home pagetask_wikipedia = create_task("wikipedia.com")tasks[task_wikipedia["socket"].fileno()] = task_wikipediafor fileno in tasks: p.register(fileno)

while True: print("polling")fds = p.poll() # `poll` returns a list of tuples (fd, mask) # fd is the file descriptor that is ready for some operations # specified by the bit mask.

for fileno, mask in fds: context = tasks.get(fileno)

state = context["state"] sock = context["socket"]

# check if the file descriptor is known if context is None: continue

# the flag EPOLLOUT will tell us when the socket is done # connecting to the server and ready to send data if state == State.CONNECTING and mask & EPOLLOUT: size = sock.send(b"GET / HTTP/1.1\r\nHost: example.com\r\n\r\n")

context["state"] = State.RECEIVING

# the flag EPOLLIN will tell us when there's any data # in the socket's buffer to be read elif state == State.RECEIVING and mask | EPOLLIN: context["data"] = sock.recv(1024)

# we might not receive all the data at once # so in the real code we should check if we # received everything we expected from the server # but for the sake of simplicity we'll stop as soon as we get # some data back. context["state"] = State.DONE break

# stops polling when all tasks reach the state DONE for ctx in tasks.values(): if ctx["state"] != State.DONE: break else: break

print(tasks)

The code above makes two HTTP requests using a single process and running it with time, it prints 0.08s user 0.02s system 31% cpu 0.319 total similar to the first example that performed only one request.

The code looks a bit better than the previous example, but still, we need read it carefully to understand what it does adequately.

class State(Enum): CONNECTING = 1 RECEIVING = 2 DONE = 3

def create_task(host): sock = socket.socket(type=socket.SOCK_STREAM) try: sock.connect((host, 80))

except BlockingIOError: pass

return { "host": host, "socket": sock, "state": State.CONNECTING, "data": None, }A task is represented as a dictionary containing the website to fetch, the socket used to make the HTTP request, the data that received, and its state that can be any of the following:

CONNECTING: waiting for the connection to be readyRECEIVING: waiting for the server to send dataDONE: there’s nothing else to do.

p = epoll()

tasks = {}# create the first task that will fetch example.com's home pagetask_example = create_task("example.com")tasks[task_example["socket"].fileno()] = task_example# create the second task that will fetch Wikipedia's home pagetask_wikipedia = create_task("wikipedia.com")tasks[task_wikipedia["socket"].fileno()] = task_wikipediafor fileno in tasks: p.register(fileno)

Then it creates the two tasks and registers their file descriptor with an instance of epoll. Now, it’s ready to poll.

while True: print("polling")fds = p.poll() # `poll` returns a list of tuples (fd, mask) # fd is the file descriptor that is ready for some operations # specified by the bit mask.

for fileno, mask in fds: context = tasks.get(fileno)

state = context["state"] sock = context["socket"]

# check if the file descriptor is known if context is None: continue

# the flag EPOLLOUT will tell us when the socket is done # connecting to the server and ready to send data if state == State.CONNECTING and mask & EPOLLOUT: size = sock.send(b"GET / HTTP/1.1\r\nHost: example.com\r\n\r\n")

context["state"] = State.RECEIVING

# the flag EPOLLIN will tell us when there's any data # in the socket's buffer to be read elif state == State.RECEIVING and mask | EPOLLIN: context["data"] = sock.recv(1024)

# we might not receive all the data at once # so in the real code we should check if we # received everything we expected from the server # but for the sake of simplicity we'll stop as soon as we get # some data back. context["state"] = State.DONE break

# stops polling when all tasks reach the state DONE for ctx in tasks.values(): if ctx["state"] != State.DONE: break else: break

Everytime it polls for new events, it gets a list of all the descriptors that are ready for some operation, and then it retrieves the task context for that specific file descriptors and update the context:

- If the task is waiting for the connection to complete and it gets an

EPOLLOUTevent, it will send the request and move to the stateRECEIVING. - If the task is waiting for data from the server and it gets an

EPOLLINevent, it will move toDONEand store the received data in the context.

The process ends when all the tasks reach the state DONE.

The structure of this code can be improved, and the while loop can be transformed into a class where we register new tasks and create high-level events, like “new HTTP request”, instead of dealing with raw data; but that’s what asyncio and other frameworks provide. That’s why all of them have the word loop in their name, or somewhere in the code, under the hood, there’s always a while polling for new events.

For example, this is the while powring the Python’s asyncio loop:

events._set_running_loop(self)while True: self._run_once() if self._stopping: break

The high-level interface provided by event loops and the new keywords make the code more readable and ease the learning curve for beginners.

import asyncio

async def fetch(host): reader, writer = await asyncio.open_connection(host, 80)

writer.write(b"GET / HTTP/1.1\r\nHost: example.com\r\n\r\n")

data = await reader.read(1024)

return data

async def main(): # create a coroutine for each website to fetch example = fetch("example.com") wiki = fetch("wikipedia.com")# wait for all the coroutines to complete res = await asyncio.gather(example, wiki)

return res

data = asyncio.get_event_loop().run_until_complete(main())

print(data)

As you can see, this code is more readable, and its time is similar to the previous examples: 0.15s user 0.02s system 46% cpu 0.355 total. However, asynchronous programming requires more thinking than usual, otherwise, it might make your life a nightmare.

From Sync to Async

This is a list of truths and lies you’ll hear when discussing pros and cons of asynchronous programming with your peers.

Make code faster

Wrong. Asynchronous coroutines add an overhead to the code, so most of the times a single task is slower than its synchronous version, but they are meant to improve how you use time which is an entirely different problem.

Increase Memory Usage

Right. The coroutine context is stored in memory, so if your server is serving 10k requests, the application will need 10k times more memory because their state must be kept in in memory. It’s not usually a problem, but you need to take it into account if each coroutine requires a lot of memory.

Compatible with Synchronous Libraries

Sometimes. You can use synchronous libraries bearing in mind that they make your application less efficient and you should check that they do not assume there’s only one task running in a single threat. Watch out for global shared variables.

Use Sleep to Pause a Coroutine

Danger. You should check if your framework has any way to pause a coroutine, because if you use any standard sleep function you will pause the entire thread, and the other coroutines won’t be able to run.

async def foo(): # ... await asyncio.sleep(1) # ...

Do Not Use for CPU-Bound Tasks

Amen!. Asynchronous programming makes sense only when your tasks do a lot of I/O operations. Using it for CPU-bound tasks won’t make any difference because a coroutine will need to wait for the running one before starting.

Database Queries Are I/O Operations

Correct. I know it sounds obvious, but sometimes developers seem to forget that databases are running in another server and they should be treated like any other external service. Asynchronous programming will help applications that are “DB-bound”.

Number Of Running Coroutine Are Limited by Memory

Yes and No. Memory can be a hard limit because you can’t have more coroutines than your memory can fit, but don’t forget that they still need CPU as well.

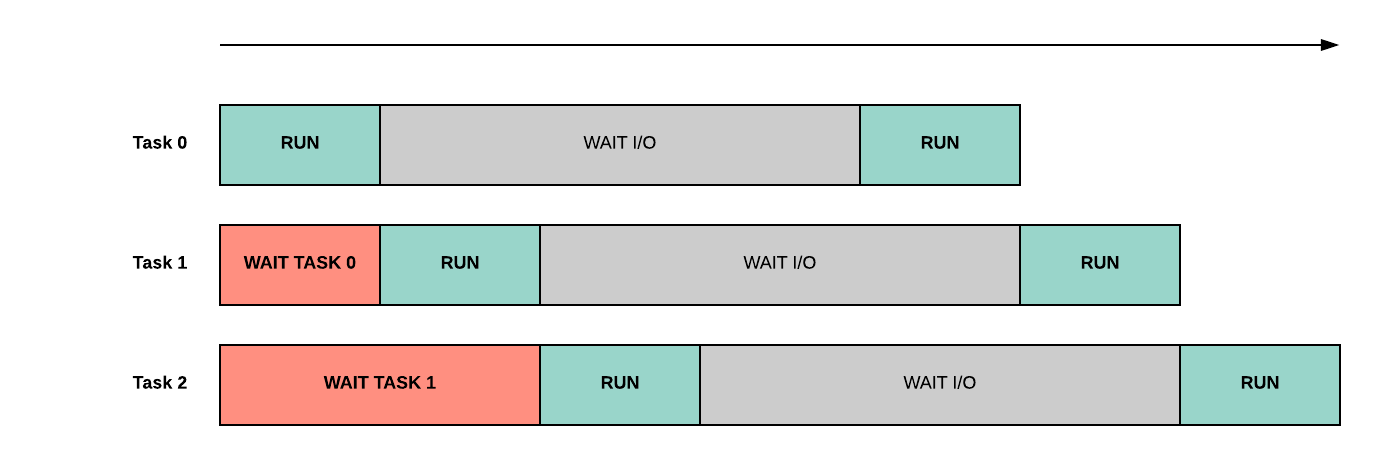

Let’s say that our asynchronous web server has a single API that takes 100ms to run but only 40s are used running some actual code, the remaining 60ms are spent waiting for the database to return some data used to populate the server response. If the server receives two requests at the same time, we’ll have a timeline similar to the one below where the overhead added by waiting for other coroutines is minimal.

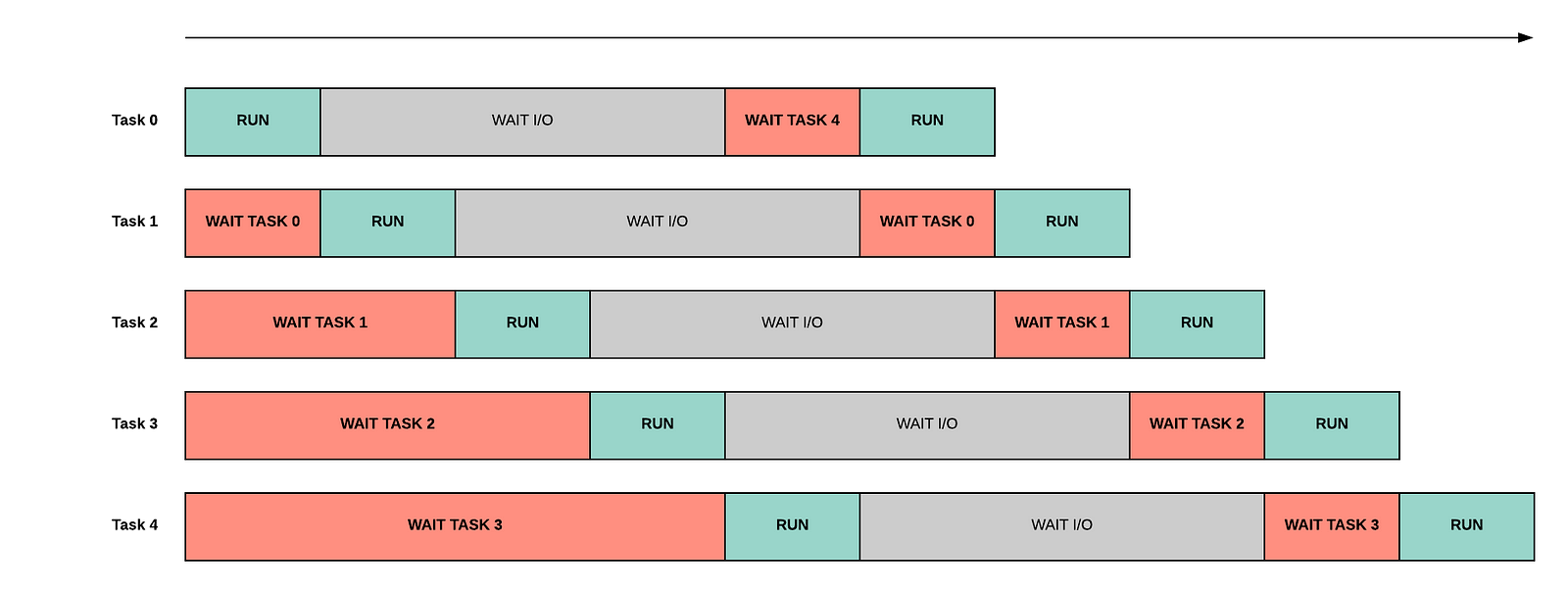

However, if we start serving more and more requests, the overhead grows and the wait time increases because of the long queue of coroutines waiting for using the CPU.

Therefore you need to understand how many coroutines you can handle before affecting the expected performances and then apply backpressure refusing to serve too many requests.

Hard to Debug

Hell yes! Your code now is switching context everytime it can in the same thread, you’ll need to instrument your application and have proper logging to understand what’s doing, but this is a challenge you’d face even writing a multithreading application.

Conclusions

If you’re new to asynchronous programming, you should invest some time trying to understand how it works and how it can be suitable for your use case, because it’s a double-edged sword: it can either boost your application or be a never-ending source of problems.