Picking Up the Pieces

Two histories of Myst

The Myst 25th Anniversary Kickstarter raised $2.8 million from over 19,000 backers in May. Last month, the subsequent re-release of Myst entries three and four was met with fanfare. These are testaments to the staying power of one inconspicuous little game from 1993 — an anomaly created by two brothers whose prior history in the game industry was, to say the least, odd. An experiment whose budget this recent Kickstarter could’ve funded several times over.

Myst should need no introduction. It’s a puzzle-heavy, non-violent graphic adventure with a slick visual style and the simplest interface known to humankind. You, the player, are a genderless, unnamed interloper on a surreal island, a world that seems almost to have emerged from a madman’s mind. Things get weirder from here: alternate dimensions; magical books with people trapped inside; and an increasingly sinister plot. This project proceeded to sell more than 6 million copies — the highest sales of any computer game until The Sims

The ripples of Myst are visible even today, most obviously but far from exclusively within so-called “walking sims” like Firewatch: a focus on atmosphere, on a sense of being there, coupled with a seamless interface. Influence-finding, though, is not my main interest here. What follows is a history of this game’s histories. I want to analyze the dueling narratives that arose to contextualize and explain the single, seismic event that was Myst

In the beginning

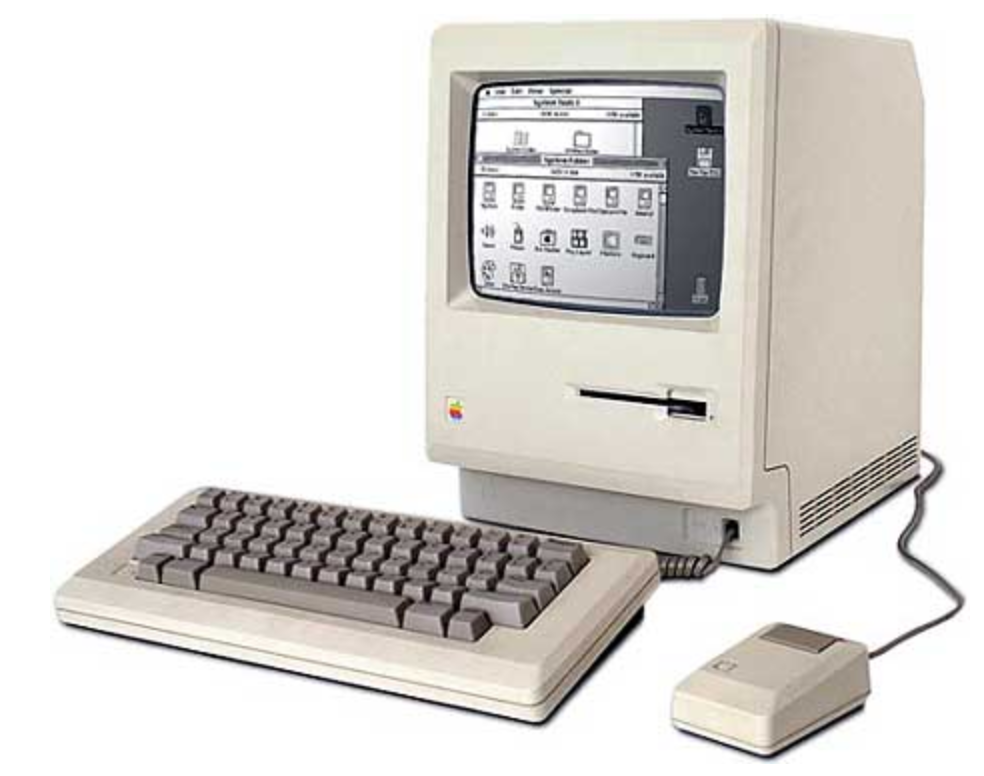

Myst creators Rand and Robyn Miller were Mac weirdos. Conveying this idea to a modern reader is challenging.

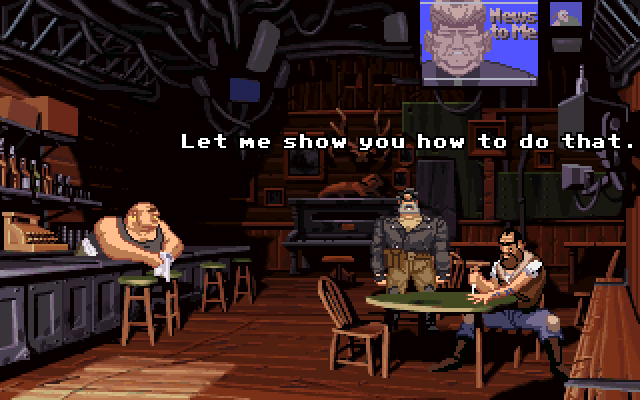

Apple’s Macintosh computer was, in many ways, a separate stream from DOS and Windows machines. Games made for it followed suit. The mouse and the window-based graphical UI were standardized on the Mac by 1984; the first true point-and-click adventure game was not LucasArts’ 1987 Maniac Mansion — with its awkward, joystick-reliant cursor — but ICOM’s Mac masterpiece Déjà Vu two years earlier. On the Macintosh, the left-field experimentation of Chris Crawford’s art games Trust & Betrayal and Balance of Power was in the water supply. Budgets were low and concepts were sky-high.

Before stumbling across its hit, the Millers’ company Cyan released three bizarre, goalless children’s games for the Macintosh: The Manhole, Cosmic Osmo and Spelunx. All followed the Myst format. Their interfaces were simple, their perspectives first-person, their controls mouse-based. They were deeply, irresistibly weird anti-games designed for non-gamers by guys who weren’t themselves especially interested in games. Most of all they were “worlds,” as Robyn Miller put it in 2013.³ Worlds inside the computer.

Books could be — indeed, have been — written about the concept of the “world inside the computer.” This is the true starting point of the computer game as such, and the enduring link between mainframe, DOS, Macintosh and Windows game development. All computer games are descendants of that first virtual world, the text-only Colossal Cave Adventure (1976–77), in one form or another. A few years later, Infocom’s Zork expanded and polished the idea. Both games were formative experiences for Rand Miller,⁴ and Zork II was, by the time of Myst, among the only games Robyn Miller had ever played.³ As Rand put it in 2015:

The feeling they provided was my first sense of actually exploring a virtual space on a computer, as opposed to simply moving through nondescript grids. I remember thinking that it was interesting to have an experience with a computer that would become the basis of a rather bizarre story that I would relate to co-workers the next day. “Last night? Well, I stumbled on a small cabin in the woods, and found a secret trapdoor underneath a rug that led down to an underground kingdom.”⁴

“Virtual reality” today is cynical Silicon Valley marketing-speak; in 1991, when Myst began development, it was an overpoweringly real and present necessity. Computers were magic in the 1970s, ’80s and ‘90s. They were expensive, foreign, mysterious, Narnia-esque portals to other worlds: their true nature and potential were unknown, unmapped even by their own engineers. People craved virtual reality. The Infocom text adventures — each one a vast computer-world — saw incredible commercial success, even on the Macintosh. So much success, in fact, that their DOS-style command-line interfaces became a threat to the Macintosh brand.⁵

The key to understanding Myst is this juxtaposition. It’s the glorious strangeness of Macintosh outsider art matched with the highest ideals of Zork. Fundamentally, right down to the way it requires the player to draw maps and take notes on physical paper, Myst is a text adventure plus graphics. But this design framework was run through the anti-game aesthetic of Mac development. The Millers didn’t want to make a game; they didn’t even have a demographic in mind, beyond themselves and the many others who didn’t care much for games.³ It was this magic mix that carried Myst into millions of lives, that sparked a gold rush and, ultimately, that made it the game industry’s favorite scapegoat and whipping boy for over two decades.

A long, long explosion

We live in an era of instant success. Infinity War made $1.7 billion in under a month. Call of Duty: WWII made $500 million in three days. It feels natural, when talking about hits, to talk about launch parties and $300 million advertising blitzes and day-one fistfights in the waiting line that stretches around three city blocks, probably lined with tents. This is the world The Phantom Menace gave us.

By and large, that wasn’t how computer games operated in the 1990s. It wasn’t how the adventure genre operated. And it definitely wasn’t how Myst operated.

When Myst launched, a typical hit computer game sold 100,000 copies in the long run — maybe its first six months, its first year; maybe longer. Even by 1998, only around 5% of new computer game releases hit that mark in their lifetimes.⁶ At GDC 2013, Robyn Miller recalled the moment when Cyan thought Myst could sell 100,000 copies, and the crowd laughed.³ It was a good joke. But it was grounded in a truth that many younger members of that audience wouldn’t have grasped.

Myst sold 100,000 copies, all right. It was a surprise hit on the up-and-coming CD-ROM format, already in the process of being popularized by Trilobyte’s odd interactive horror movie The 7th Guest. Suddenly “multimedia” and “new media” were the words on every venture capitalist’s lips; The New York Times was profiling the high-tech “Gurus of Multimedia Gulch” in San Francisco. Hollywood money, drawn by the promise of virtual realities with live actors as their stars, started to pour into Silicon Valley. Released in September 1993, Myst reached 200,000 customers by April — despite its being a Mac exclusive until March.⁷ Modest by today’s standards, but comically successful given its circumstances. The important part is that it kept selling for the next eight years.

Most people don’t want to sift numbers and statistics. There’s something deeply dry and unsexy about it; can’t we leave it for the suits and their accountants to parse? But nothing was more important about Myst than its revenue and reach. “Follow the money” isn’t just a political aphorism: it’s our method of understanding everything that’s happened or might happen or will happen or won’t happen in a late-capitalist world of enterprise. It took the naïve idealism of Rand and Robyn Miller, with their total lack of economic thinking, to create this magic. What happened afterward — down even to the games that were allowed to happen afterward—was the domain of the bottom line. And this realm was shaped inexorably by what Myst was doing at retail.

With that in mind, try to bear with the number-crunching that follows.

Myst wasn’t the fastest seller. Doom II was actually the best-selling PC game of 1994.⁸ Its blood-and-guts simplicity drew a different crowd: mostly excited young guys with disposable income and brutal FOMO (which didn’t yet exist). The 7th Guest outran Myst for a couple of years, too. By the time Myst finally broke the magic number in mid-1995 — the barely-ever-happened 1 million mark — The 7th Guest was at 1.5 million.⁹ But the blockbuster glamour of Doom II and Guest ultimately capped out between 2–3 million sales apiece.¹⁰ By comparison, it seemed at the time that Myst’s audience might be the entire human race.

Unlike with most computer games, Myst didn’t slow down over the years: it sped up. In the US, the world’s biggest computer game market at the time, Myst beat Doom II for the crown in 1995.¹¹ It beat Warcraft II the next year, with a ludicrous 850,000 sales and $28.8 million in gross revenue just that year and just in the United States.¹² It was finally toppled in 1997 by its own sequel, Riven, but still nabbed second place and another 870,000 sales.¹³ In 1998, despite its being five years old in an age characterized by rapid technological decay — as Weird Al put it in 1999, “My new computer’s got the clocks, it rocks / But it was obsolete before I opened the box”—Myst claimed third place. It actually outsold Riven that year: 540,000 copies to 355,000.¹⁴

The game was seemingly indestructible. Competitors were frustrated. “Myst is an anomaly — there is no logical reason to explain its success”, said Gary Griffiths of SegaSoft, one of the most ill-advised and incompetent PC publishers of that era. “All you need to do is look at the customer base to know that.”¹⁵ This was 1998, and these people hadn’t cracked the code. Nobody knew why Myst kept appealing to players who’d never bought a game before.

SegaSoft published a Myst clone, Obsidian, that earned roughly $4 million in roughly two years.¹⁵ Myst earned $132 million in the US by late 1997.¹⁶ Obsidian sold a little under 100,000 copies. There were 4.23 million units of Myst bought domestically by 1999,¹⁷ and 6.3 million internationally by 2000.² The original Myst, an eight-year-old game built for System 7 and Windows 3.1 and Windows 95, sold another 43,000 units in 2001. With its remakes and re-releases that year, this number rose to 130,000.¹⁸

This paradigm-shattering success made Myst impossible to escape. Everyone knew this game; everyone was talking about it. Corporations wanted a piece of the pie, but couldn’t get it; pundits wanted to say something valuable about the situation, but Myst seemed resistant to prediction or interpretation. How do you wrestle with this thing that’s driving the industry without being part of the industry? Computer game people understood Quake II, released around the same time as Riven: it sold to the same guys who read PC Gamer, an audience you could predict. The Myst games didn’t.

“In some ways, these games aren’t competing”, said the great Ann Stephens of PC Data in 1997, “because they’re attracting completely different kinds of people”.¹⁶

The great divide

Computer games were, at one time, unified. We didn’t even have the term “casual game” in 1993, let alone the idea that a first-person shooter (then an unnamed genre) could be considered a “hardcore title.”¹⁹ There were people who played computer games, and people who didn’t. People who got way into golf or Harpoon or hearts or text adventures — those were the “hardcore” players, in that they played their chosen field obsessively.

When Myst and the CD-ROM finally broached the mass market, this ecosystem was disrupted. Myst had, Robyn Miller makes clear, been designed to appeal to non-gamers. It sold to them. Enthusiast magazines like Computer Gaming World couldn’t set the taste for the industry anymore: there were millions buying games who didn’t read these magazines. An entirely new breed of player. In this situation, what could be more natural than concocting an us-and-them formula? In a very real way, it was already true.

The great narrative of Myst is that the “hardcore” game press and playerbase lambasted it when it launched. Disowned it. A slideshow, they called it. Abstruse, idiotic puzzles; pretty graphics and not much depth. “Critics and hardcore game players universally panned it as a slide-show that had little actual gameplay interaction”, claimed PC Gamer’s Michael Wolf in 2001.²⁰ That same year, a columnist for Maximum PC recalled Myst as a “tedious code-breaking and switch-throwing mess”, and saw its then-new remake realMYST as “a pointed reminder of why the press dumped on the original so heavily when it came out.”²¹

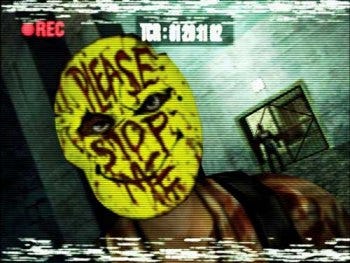

Game developers shared this sentiment in the late ’90s. “When I look at Riven and Myst, they insult me,” said Sanitarium’s Travis Williams at a seminar during GDC 1998. He derided them as “a whole bunch of pretty pictures around those wooden peg puzzles”; and the crowd laughed and clapped. Moments later, a Mindscape employee denied that the two hits were adventure games at all.²² Cyan couldn’t have been less welcome at this event, entitled “Are Adventure Games Dead?” Many in the audience believed that Myst had killed the genre.

Myst became tied to the death of adventure games, in fact, for many years. As the 1990s wore on, the famed “LucasArts style” — failure-free, notation-free, dialogue-heavy, streamlined, linear, jokey, filmlike — became identified irrevocably with the adventure genre by game publications and an increasingly fractious audience. Yet Myst was almost the polar opposite, and its immediate influence on the field was much wider than anything Lucas managed until the 2000s. Almost everything became Myst-ified to some degree, although most today don’t remember John Saul’s Blackstone Chronicles, Black Dahlia, Dust, Starship Titanic, Lighthouse or Zork Nemesis. This style was a LucasArts fan’s worst nightmare. As PC Gamer put it in 1997, “[N]othing good could ever come of an adventure created with Macromedia Director.”²³

To many at the time, Myst’s influence looked like the creative death of a medium, to be followed (it seemed) by commercial death.²⁴ Even Myst’s adherence to tradition — its note-taking and nonlinearity; its sense of virtual reality; its general lack of filmic exposition — felt more and more like an aberration in a world of Full Throttle and The Curse of Monkey Island. These games manifestly were not virtual realities, but that didn’t seem to matter: especially for the latter, the awards from enthusiast magazines rolled in regardless. In just a few years, the industry had drifted far from the era in which Myst made sense. Its concerns were those of text adventures and Mac outsiders; the surging Doom generation had never known them.

By 1996, the blowback against Myst and its children had begun. An editorial in boot’s debut issue compared the game to Pandora’s box; to the author, it had started a revolution of “stultifyingly boring and fatally uninventive" dreck.²⁵ Denial soon set in even regarding Myst’s monster success. Beginning a long tradition in computer games, certain players and writers started trying to explain away the sales. When Quake’s retail launch bellyflopped, beaten on the charts again by Myst, CNET’s resident “GamerX” would have none of it. “Remember, though, these figures only reflect sales in the stores, not sales online”, he wrote. “Do you really think the original Myst is outselling Quake? Wake up, man!”²⁶

What “GamerX” said about the figures’ exclusion of online sales was true, but irrelevant: even by late ’98, brick-and-mortar stores still accounted for three-fourths of computer game sales.²⁷ Myst really was outselling Quake; and the industry’s fear of the reality that this truth represented grew by the day. To many insiders, this was the reality of non-gamers, outsiders, people who didn’t understand quality, idiots, the unwashed masses banging on the hallowed gates. Reflecting on the 1997 performance of Myst and its sequel, a nameless staff writer for PC Gamer commented that “the hard-core gamers here at PC Gamer are still trying to figure out how the gruesome twosome of Riven and Myst continue to sell in phenomenal amounts.”¹³

They weren’t really trying to figure it out, though. They’d already offered an explanation when they gave Riven a Special Achievement in Hype award in the previous issue:

Operating from the game’s single selling point as the sequel to Myst, one of the best-selling PC titles ever (another perplexing mystery), Riven managed to invade our collective consciousness to the point at which everyone, even millions of non-gamers, knew it was coming and that it was big, so everybody rushed out to buy it. Never has a game with so little to recommend about it been bought by so many.²⁸

There was nothing to it; the standard story: stupid lemmings, McDonald’s culture: the world of dumbed-down mass-market entertainment, all flash and no substance. “If rendered adventures appear in a museum, they’ll need only two exhibits”, wrote Jonathan Nash of PC Gamer’s British edition in 1998. “One is the millions-selling Riven, just to remind everyone that you can never, never know fully just how appallingly moronic the human race can be.”²⁹

By this point, the freshly-formed “hardcore” contingent had stopped bothering. Most enthusiast magazines barely addressed Myst and the Myst-lings anymore. “Denny Atkin, features editor at Computer Gaming World, says his magazine doesn’t cover immersive games [read: Myst-alikes] because his magazine’s audience just isn’t interested in them”, reported Salon in 1998.¹⁵ In other words, an entire demographic had finally receded into its shell.

Riven was, in 1997, the biggest-ever computer software launch this side of Windows 95.³⁰ But the hype came from the mainstream press: gaming magazines were conspicuously silent. So silent, in fact, that Strategy Plus’s underrated columnist Cindy Yans had a bone to pick with them about it. “[W]e didn’t see a heck of a lot about Riven in the gaming press during the months prior to its release”, she said at the time. “Are they crazy? Or did they just forget?”³¹

Feeling embattled and desperate, the self-anointed hardcore did the only thing they could in the face of an indestructible so-called “enemy”: shut their eyes, cover their ears and yell, “Lah, lah, lah.” Circle the wagons. Watch out for “casual” gamers. Don’t pay attention, and maybe it’ll all go away. Surely those sales are overstated, anyway.

“I mean, when’s the last time you heard someone confess that he had played Myst all night?” asked GamerX in 1997. “1994?”³²

The other story

The irony was that the mainstream, in many respects, took the mirror-inverse view of the Myst phenomenon.

In a time before Farmville and Minecraft and Fortnite — “even parents are relaxed about it”, claims The Guardian — made computer games mainstream-palatable, many outsiders saw them as a hobby for antisocial nerds and juvenile delinquents. Myst promised another way. It was non-violent, contemplative: artsy. It had nothing to do with Satan.³³

As a result, Myst became the general public’s anti-Doom. Both were released in 1993, but they embodied vastly different visions of what games could be. “To many, Myst seemed like the good twin of the evil Doom”, the academic text Digital Play put it in 2003. The differences between these games were, to average people, far more pronounced than any similarities they might have shared. Again, Digital Play:

Where one was violent, the other was pacific. While Romero and his disciples at id swaggered with a calculated ‘badness’ that smacked of high-tech Satanism, the Millers were pious but soft-spoken Christians. Where Doom was the descendent of arcade shooters, the ancestors of Myst were the children’s games Cyan had developed for the Macintosh computer, games with titles like Spelunx and the Caves of Mr Seudo. Where Doom was a celebration of speed and terror, Myst was serene and beautiful.³⁴

Myst was also smart, which Doom — for all its many qualities — never even attempted to be. This game placed no emphasis on reflexes, but a massive one on patience and lateral thinking. To older non-gamers in the ’90s, it felt accessible: it could be solved through the same quiet, logical contemplation as The New York Times crossword puzzle. It began to look like computer games’ path toward adulthood, a final escape from adolescent-male power fantasies.

All of this was the narrative of the mainstream press, which at the time was separated by an uncrossable chasm from enthusiast magazines. Forgive the long quote, but these words from the Los Angeles Times in 1997 must be read in full:

Not so long ago, many in the industry believed the game business was poised for greatness. PC sales were booming, and every sale created a household of potential new customers.

This was accompanied by the hope that typically affluent and educated PC buyers might be ready for something more sophisticated than the shoot-’em-up titles that dominate the market for dedicated game machines such as the Sega Saturn and Sony PlayStation.

If any game served as a symbol of these lofty aspirations, it was an unheralded gem called Myst.

Introduced by Broderbund in the fall of 1993, Myst enthralled players with surreal graphics and sounds, right down to the lapping tide and screeching sea gulls in the game’s opening waterfront scene.³⁵

This is what Myst represented to the wider public. It was a sign of the industry’s future. It was an art film drawing crowds in an otherwise-scuzzy theater, sandwiched between screenings of Rambo and Friday the 13th. It was a portal into a beautiful, hyperreal otherworld that regular people actually wanted to visit. For the enormous New Age contingent in the ‘90s, its strange and peaceful atmosphere was a glimpse of white-people Nirvana.

When the Wall Street Journal reported on Quake II’s launch, you could feel the disdain drip from every line, as it pilloried the game’s young and unsophisticated fans with their own words. “It’s got cool stuff like flies buzzing over dead bodies”, raved one 16-year-old. The owner of fansite Planet Quake was quoted as mentioning “a smorgasbord of slaughter.” Near the end of the article, though, Riven and Myst appeared as a counterpoint. Dichotomies were drawn—rival games; “one appealing to the intellect and the other to primal instincts” — and sales figures cited, both in Myst’s favor. Thanks to Cyan’s hits, even a paper this conservative couldn’t write off computer games entirely.¹⁶

And yet Myst was losing the war for the industry’s soul, in the public’s mind. The Los Angeles Times reporter quoted above, Greg Miller, argued as much. By 1997, he saw artistic games as a dying dream. “Most of the other top-selling games last year [besides Myst] had the high testosterone quotient of a Schwarzenegger or Stallone action movie and the bloodthirsty title to go with it”, he wrote. He cited the sales failure of the lovely Neverhood Chronicles—one of many commercial bombs produced by a doomed, quixotic venture under the name of DreamWorks Interactive — as proof that computer games were relapsing into stupidity.³⁵

Beyond Riven, there were no other Myst-tier adventure game hits. Nothing else in computer games penetrated the mainstream consciousness like these titles had. There were huge successes, certainly; but the industry no longer even allowed for an event as big as Myst to occur. The late ’90s were a new world of shortening shelf-lives, shrinking shelf space and dying specialty retailers. Ascendant big-box stores wanted games to boom and then, ideally, to exit the shelves and make way for the next million-seller. As GT Interactive’s head put it in 1997, “If Myst came out in this retail environment today, it may never have even seen the light of day”.³⁵ It’s telling that even Riven didn’t match the exact sales pattern of its predecessor.

All of which was a problem, in the mainstream public’s mind. Games as a whole actually seemed to be getting more violent, more adolescent, no matter how much Myst sold. Computer gamers’ average age dropped and a men’s-magazine style of coverage—spearheaded by British journalism and American fansites, then blown up online and in print by Imagine Media and Ziff Davis in the US—claimed the industry.³⁶ Myst aside, the hobby’s reputation was getting worse; and developing irresponsible games was becoming a mark of pride for many inside the field.

By 1995, politicians like Joe Lieberman were angry, and then-First Lady Hillary Clinton wasn’t far behind.³⁷ Lieberman’s hit list the following year, the “Ten Least Wanted Computer Games”, included Bethesda Softworks’ The Elder Scrolls II: Daggerfall.³⁸ These people still saw games as children’s toys, somehow, and the idea of a child’s blowing up strippers in moronic products like Duke Nukem 3D scared them. (Minors were, unfortunately, doing just that — but that’s another story.) Battles over censorship raged. When school shootings started getting blamed on computer games, all hell broke loose.

Columbine wasn’t the first. In 1997, you had Heath, which claimed the lives of three girls. About a week before Columbine, in April 1999, those victims’ families filed a lawsuit against a scattershot assortment of media companies — including the producers of Doom — for their alleged inspiration of the shooter to shoot. The connection of Heath specifically to games, though, was questionable. Columbine was an entirely different animal. Here, the shooters avidly played Doom, described the planned shooting as Doom-like. The link couldn’t be scrubbed away, whether we liked it or not.³⁹

“The tone after Columbine was one of absolute certainty[. …] Society was absolutely behind this issue of linking video game violence to mass shootings”, game researcher Chris Ferguson recalled this year. Newt Gingrich got involved, as always, and the Clintons continued their long hunt for causation. The legal battles between the game industry and the wider world — opportunists, do-gooders and the legitimately concerned alike — defined the medium’s next decade in the US. Many inside the industry felt that the honor of stuff like Manhunt and Postal 2 was a hill worth dying to defend.

In all this chaos, a non-gamer might wonder: what happened to Myst and the revolution it promised? Why did Doom father the new industry? Who asked for this thematic race to the bottom? Mainstream media outlets have returned to these questions over the years. For Vice, Myst represents the beleaguered “alternate timeline”: the sad story of what could have been. As the magazine’s Mike Diver wrote in 2015:

Would the last 20-odd years have been different — for games and those who play them — had Myst been the template upon which more titles were based? Would gaming culture have been less male dominated, a friendlier place to tweet in? Would video games have avoided being dragged through the tabloid press in the wake of the Columbine massacre and Anders Behring’s rampage of 2011? Perhaps. Maybe we’d all be a little friendlier to each other right now, in person and online, with multiplayer games emphasizing cooperation over annihilation.⁴⁰

A much better publication, the late-great Grantland, made a similar case on Myst’s 20th anniversary. “Twenty years ago,” wrote Emily Yoshida, “people talked about Myst the same way they talked about The Sopranos during its first season: as one of those rare works that irrevocably changed its medium.” The sense of forlornness in that sentence continues throughout the article, which is required reading in its entirety. For Yoshida, Myst was a failed coup against the twitch-gameplay status quo. This was 2013, and “the gaming industry couldn’t be further from the quiet, achingly lonely puzzler it had embraced two decades ago.”⁴¹

For the mainstream press, Myst was a beautiful failure, finally defeated; and we were left poorer for it. Computer gaming would always be Doom-ed.

The persistence of (false) memory

At first glance, the two histories related above are diametric opponents. One, on the mainstream side, tells of a heroic savior ignored; the other details an antichrist narrowly (if at all) defeated. What unites them is an inaccuracy of memory.

The game historian Laine Nooney has written eloquently on the issue of memory in this medium. Real history is scarce for us: most of the industry’s past is held as an informal collective chronicle, a shared urban mythology that the initiated all “know” but cannot say how or why. There is no lineage of tradition-keepers, as in the ancient world; but there isn’t a modern historico-critical body to keep the story straight, either. As a result, game history has been relegated to a kind of memorial natural selection: the industry’s history is nothing more or less than what those still playing games remember that history to be.

Two histories of MystMyst (1993) by Cyan and Brøderbund.The Myst 25th Anniversary Kickstarter raised $2.8 million from over 19,000 backers in May. Last mon -m mat guid back .net fcm std into 能夠

Picking up Jewels

There is a maze that has one entrance and one exit.

Jewels are placed in p operator 一個 技術 -- def oot lap mina https 題目大意:

輸入n,p;n個點,p條路

接下來n行輸入c[];在各個點需要花費的時間

接下來p行輸入u,v,w;u點到v點的路需要花費時間w

求經過所有點且最後回到起點的最少花費時間

ht Farmer John變得非常懶, 他不想再繼續維護供奶牛之間供通行的道路. 道路被用來連線N (5 <= N <= 10,000)個牧場, 牧場被連續地編號為1..N. 每一個牧場都是一個奶牛的家. FJ計劃除去P(N-1 <= P <= 100,000)條道路中儘可能多的道路, 但

alter session set workarea_size_policy=MANUAL;

alter session set db_file_multiblock_read_count=512;

alter session set events '10351 trace name cont Chatting it up with NestJS and Angular 6: Setting up the ProjectThis is the first article in a series covering the development of a chat application. Why a Researchers have discovered a new anti-epileptic drug target and a whole new approach that promises to speed up the discovery of future drugs to treat debi A new method of analysing heart scans with artificial intelligence (AI) is helping predict which patients are at risk of a deadly heart attack years before Sales strategy and the future of customer engagement is in my DNA. As we all see and know, agility, automation and artificial intelligence is changing the ETHletter is a mail service - like Gmail, Yahoo mail or any other. But there's one big difference - during the email creation, you can set up the price for JavaScript built-in methods help us a lot while programming, once we understand them correctly. I would like to explain three of them in this article: the Speed up the Web Development Productivity with SeleniumImagine that you are developing a website, and every time you restart, fixing bugs or adding feature Thank you so much for joining us! What is your “backstory”?I started my career working with ad agency Saatchi & Saatchi, where I discovered early on th This story is for Medium members.Continue with FacebookContinue with GoogleMedium curates expert stories from leading publishers exclusively for members (w Hey team,Our next team meeting is dedicated to Core Values, which are essential to building our culture. It occurred to me that before this meeting, I shou

Translation systems from Google, Facebook, and Amazon require training models to look for patterns in millions of documents -- such as legal and political The tail of the transaction log usually refers to the contents of the database's transaction log that has not been backed up. Basically, every time you pe

Brian shows the unboxing of the element14 IoT Learner Kit. He then shows you how to assemble the components, including installing the SD card.

To set 配置 soft mic target clas 無法執行 ssh pull 開發 問題出現的情景:使用git pull拉取開發的代碼到測試服務器,報錯:

ssh: Could not resolve hostname git.****-inc.com : Tempo rate mes europe escape layer graphic iot led oss Most Australians are not homophobic; consider the number runescape gold of homosexuals e 相關推薦

Picking Up the Pieces

Picking up Jewels

USACO 2008 November Gold Cheering up the Cows /// MST oj24381

[USACO08NOV]安慰奶牛Cheering up the Cow BZOJ 1232 Kruskal

Script" References MACLEAN‘s post Speed up the index creation.

Chatting it up with NestJS and Angular 6: Setting up the Project

Big data method could speed up the hunt for new drugs

AI flags up the risk of fatal heart attacks years early

Freeing up the sales force for selling, listening and automating with AI

set up the price for incoming emails [beta] | Hacker News

Let’s clear up the confusion around the slice( ), splice( ), & split( ) methods in JavaScript

Speed up the Web Development Productivity with Selenium

Female Disruptors: Purva Gupta is shaking up the AI world with emotionally

Carbon Farmers Work to Clean Up the World’s Mess

Don’t Fuck Up the Culture

Model paves way for faster, more efficient translations of more languages: New system may open up the world's roughly 7,000 spok

Backing up the tail

Setting up the element14 IoT Learner Kit

ssh: Could not resolve hostname git.*****-inc.com : Temporary failure in name resolution fatal: The remote end hung up unexpectedly

the rs gold with up to $18 Vouchers to Vic Hati, S