The Mathematical Nature of Musical Scales

The Mathematical Nature of Musical Scales

One-sentence summary: In this article I will explain the math for the Just intonation and Pythagorean tunings for the diatonic major scale (all the white keys on the piano).

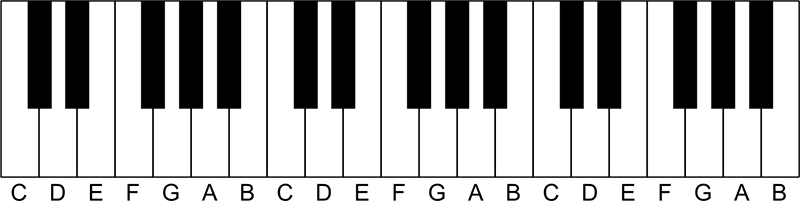

In the preceding article The Physical Nature of Musical Sound I have talked about how air vibration affects a human eardrum and causes the perception of sound pitch. I used a piano as a case study, noting that there are metal strings inside the piano that vibrate at different rates. The vibration frequencies to which the strings should be tuned, is the subject of this article. Please refer to the piano keyboard diagram above, for the names and location of piano keys.

Although I’m using a piano for case study, this applies to all musical instruments. Wind instruments, such as a flute, have holes in carefully calculated locations to produce sound at desirable frequencies. Wind instruments with no holes, such as a trombone, require the player to remember how much to elongate an air pipe of the instrument so as to produce the desired air vibration. On a clarinet or a saxophone the player can alter the pitch by pressing or relaxing a reed. Even on a violin, it is not enough to tune the strings: there are no frets like on a guitar and a player must remember where to depress a string.

Thus, tuning a musical instrument is not only a theoretical exercise for the instrument maker. Musicians are expected to hear and memorize the way the musical notes and intervals should sound. Here is a demonstration of what tuning skill is required of a violin player, in which a violin player is asked to switch between three different tuning schemes. (Two of these schemes I discuss at length in the remainder of this article.)

However, not only it is hard to memorize the proper pitch, it is hard to determine theoretically what the frequencies should be. Attempts to find the right frequencies goes all the way back to Pythagoras, an ancient greek philosopher from the 6th century BCE. The Pythagorean tuning is still in use today.

In this article I will abuse terminology by saying that a piano key is tuned. Actually, what must be tuned is the corresponding string inside the piano. Remember that a piano key is connected to a hammer which hits a tight string. The sound you hear is the vibrations of that string. (Even more precisely, the vibrating string vibrates the air around it; then, that air propagates a compression wave; the wave vibrates your eardrum; this sensation is processed in the brain as a perception of sound.)

The mathematics of music began after Pythagoras drew some conclusions after experimenting with vibrating strings of different lengths. By touching lightly onto a tight vibrating string with a finger, one can force the string to vibrate in a standing wave pattern which will have a stationary node in the position of the finger.

Refer to the diagram below. Let’s say a string vibrates as shown in the top vibration form. If you now press with a finger at the centre of the string, you will get the second vibration form, with a stationary node forming in the centre. Or, if you instead pressed your finger at a third-in from the end, the string would vibrate as a stationary wave shown at the bottom, with two stationary nodes forming.

What are the relative frequencies of vibrations in each case? Remember that a frequency is an inverse of a period. So, what are the periods in each case? Relative to the first wave, the period of the second wave is twice as small, and of the third waveform is three times as small. Therefore, relative to the first wave, the second wave is twice as frequent, and the third wave is three times as frequent.

Of special interest is the frequency that is double the original. Pythagoras noticed that doubling, quadrupling, or even halving a frequency doesn’t significantly alter the resulting sound. The pitch is different, but the perception is that the sounds are the same in a fundamental respect. These double or half frequencies are called octaves.

What are some uses of octaves? One use case is for singers to sing octaves apart. It is easier for a man to sing lower pitches, and for a woman, higher pitches. Therefore, a woman sings an octave higher than a man. The song Summer Love from the movie “Grease” is an example. You can hear it clearly in the last 30 seconds of the song. Also, octaves can be used for melodic movement, rather than harmonic convenience. Listen to the first 10 seconds of the song My Sharona by the band “The Knack”.

Although an octave is an interval which could have any absolute frequencies as endpoints, the range of musical sound spectrum has been divided in a particular way into a set of adjacent octaves. These intervals are referred by number. The centre of the piano keyboard has octaves number 3 and 4, and they are the common range of most music. Normally, octaves are between each C key and the next C key. (Refer to the keyboard diagram at the beginning of the article.) However, in this article I will ignore the standard division, and consider octaves as between each A key. The reason is that piano is tuned based on the A key, not on the C key. Interestingly enough, the lowest key on the piano is not C, but A.

What frequency should we assign to the A keys, then? Taking 440 Hz as the starting vibration frequency we can form octaves by multiplying or dividing this frequency by 2, repeatedly. We get this sequence of frequencies for the A keys: 27.5, 55, 110, 220, 440, 880, 1760, 3520. It is not difficult to tune all the A keys to this sequence, using an electronic tuner device.

But, what about the other keys, the ones between the A keys? We can already be sure that the frequencies will doubles and halves for their namesakes in the other octaves. If a certain key E has frequency X, then the other keys “E” will have frequencies 0.25X, 0.5X, 2X, 4X. Therefore, if we can determine how to tune strings within a single octave, it would be a simple matter to translate them to other octaves. We would only need to multiply them by 2, or divide them by 2, in order to fill other octave ranges. This is also called transposing up or down by an octave.

In this article, I will denote each piano key by name followed by tuning frequency. For instance, A-220 is a piano key called “A”, tuned to emit 220Hz vibration. I will also use the word “key” and “note” interchangeably. (The difference is that notes are what is written in the musical score, while keys are what you press to voice the notes.)

The task then becomes to find the intermediate notes between A-440 and A-880. The earlier diagram with standing waves gives the frequency for one key these two A keys. Recall that we have already concluded that the third standing wave has a vibration 3-times more frequent than the first wave. If the original frequency is X, then this one will be 3X. The pitch interval between them is bigger than an octave, because the multiplicative factor of 3 is greater than 2. If we transpose 3X down one octave, we get 3X/2 for the new vibration. The ratio between frequency X and frequency 3X/2 is 3/2. If we use 440 as the value for X, then by multiplying 440 by 3/2, gives 660. Thus, we will assign 660 Hz frequency to the key “E”.

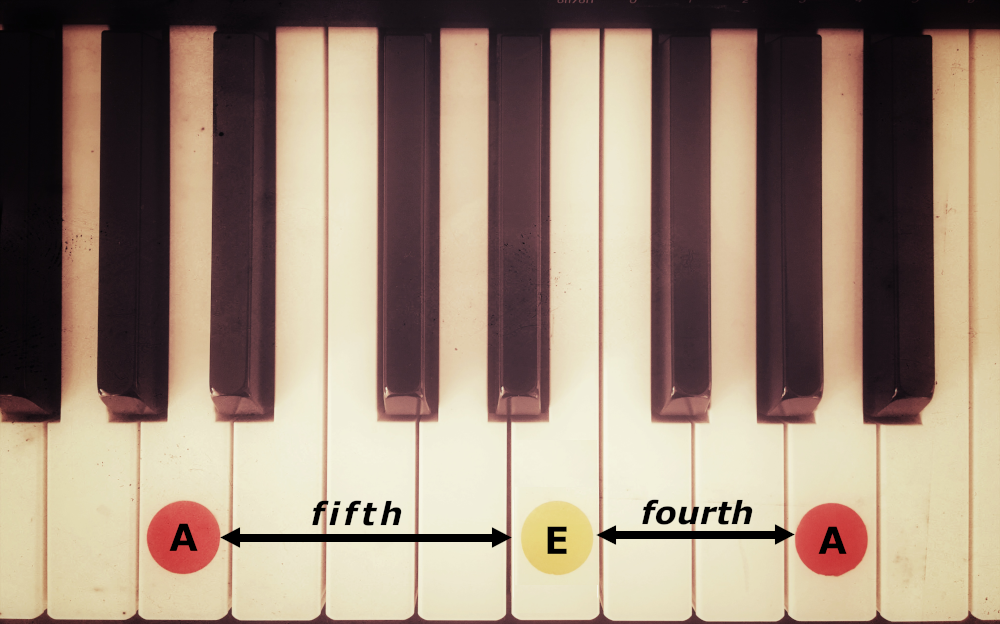

In summary, the key E, which is an intermediate key between A-440 and A-880, has been determined to have frequency 660. The ration of E to the lower A is 3/2. What is the ratio of the upper A to E? This is easy to calculate by reference to the absolute frequencies 880 and 660. The first is 4/3 times bigger than the second.

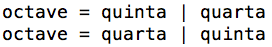

Just like the interval 2-to-1 had a name of octave, the intervals of 3-to-2, and 4-to-3 have their own names. In European terminology, the interval 3/2 is called a quinta, and the interval of4/3is called a quarta. These are latin words.

The American English names for quinta and quarta are “fifth” and “fourth”. These names correspond to the order of the intervals as observed in a basic scale — the diatonic major scale — which we are about to construct. It’s important to understand that “fifth” in this context doesn’t mean 1/5 — it means the “fifth interval of a scale”. Likewise, “fourth” doesn’t mean 1/4, but means the “fourth interval of a scale.” Since in this article I discuss fractions, I will use latin names refer to intervals whenever there’s a possibility of misinterpretation.

So, we have split an interval of an octave into two intervals. Let’s formalize it with a formula. Let’s say we have two frequencies “a” and “2a”, corresponding to an octave, and we wish to split it into two intervals L1 and L2. We want a*L1 to give an intermediate frequency X, and then X*L2 to give the frequency 2a. Simplifying this, gives the relationship of L1 * L2 = 2. The solution we found is 3/2 and 4/3.

We can generalize further by stating that to split any interval L, we must find L1 and L2 whose product equals to L. Let’s use this method to split the quinta 3/2, by finding a solution to the equation of L1 * L2 with 3/2. One of the solutions is 5/4 and 6/5.

The interval of 5-to-4 is called a major tertia, and the interval of 6-to-5 is called a minor tertia. In American English, these intervals are called major and minor thirds.

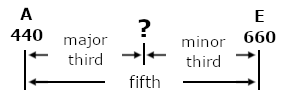

Pictorially, we did this:

The piano key that goes in place of the question mark above, is C#-550. I have calculated 550 by multiplying 440 by 5/4.

We can express the proportions 5/4 and 6/5 concisely as 4:5:6. We can also express the proportions of the scale spanning the whole octave as 4:5:6:8. Notice that 8/4 equals to 2/1 and is the octave interval. The corresponding notes as A, C#, E, A with frequencies 440, 550, 660, 880.

Let’s use the 4:5:6:8 proportions to determine the frequencies of keys in a lower octave in the range between A-220 and A-440. Multiplying 220 by 5/4 we get 275, which is the lower C# key. Multiplying by 220 by 6/4 we get 330, which is the lower E key. So the scale A, C#, E, A in this lower octave has absolute frequencies 220, 275, 330, 440.

We can express the scale over the range of two octaves as: 4:5:6:8:10:12:16. The ratio 4:16 is the two-octave interval from A-220 to A-880. Notice that each frequency in the lower octave is half of the corresponding frequency in the higher octave. The notes in the two-octave range scale are A, C#, E, A, C#, E, A with corresponding frequencies of 220, 275, 330, 440, 550, 660, 880.

To summarize, we were able to create a scale of 3 notes, that repeats every octave. Can the intervals be split further, in order to create more notes? A hint for how to subdivide further comes from the following observation: the order of the intervals doesn’t matter, so an octave can be either a quinta, followed by a quarta, or a quarta followed by a quinta. Visually,

The frequency of the note a quarta ahead of A-440, is 440 * 4/3 which equals to 586.66…. (I will round it to 587). It is the key D on the piano.

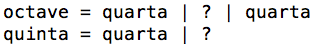

If we can begin an octave with a quarta, and end it with a quarta, we observe an “unfilled” interval in the middle:

The missing interval is the degree by which a quinta is higher than a quarta. Let’s calculate it. Let “a” denote the frequency of the root note of the octave. The note higher by a quarta is (4/3)*a, and the note higher by a quinta is (3/2)*a. The proportion between them is (3/2) / (4/3) which works out to 9/8. The interval 9/8 is called a tone. On the piano, it is the interval between piano keys D-587 and E-660.

In summary, a quinta is a quarta followed by a tone. And, an octave can be seen as a (major tertia, minor tertia, quarta), or as a (quarta, tone, quarta).

Can we subdivide further? Let’s subdivide major tertia, which has a ratio of 4:5. A possible subdivision is 8:9:10. The two ratios are 9/8 and 10/9. The first frequency ratio we recognize as a tone interval. The second ratio of 10-to-9 is new, and is called a minor tone interval. Note that we can order the two intervals in any way (because the product of ratios is the same), but for reasons that are hard to explain at this point, I will order them as a tone, followed by a minor tone.

If you are a musician, you may be puzzled at this point. You know that a major third (major tertia) is two whole tones, both of which are the same. Yet, here I am telling you that the first tone is a little bigger than the second. Indeed, musical instruments, particularly piano are tuned so that both intervals exactly the same. But this is a calculated error. The purpose is to enable modulation, which is discussed later in this article.

Let’s split a minor tertia (minor third) by separating it into a tone and something else, that we will call a semitone. The minor tertia has the proportion of 6/5. It is higher in pitch than a tone by the factor of (6/5)/(9/8), which works out to 16/15. The frequency ratio of 16-to-15 is called a semitone interval. Again, we have freedom with the order of the intervals. We need to take it in the order of (semitone, tone). The reason will be apparent later; it has to do with having a quarta as the fourth interval in the final scale. Also, notice that two semitones are not equal to a tone: 16/15 squared is bigger than 9/8.

Summarizing, our octave is now divided into the scale of relative intervals of major tertia, which consists of (tone, minor tone); followed by a minor tertia, which consists of (semitone, tone); followed by a quarta.

What about that last quarta? We haven’t yet attempted to separate a quarta into smaller intervals. We can just guess a combination, and check that the product of ratios equals to 4/3. How about a major tertia and a semitone? Let’s check: 5/4 * 16/15 equals … 4/3. (Of course, I cheated by looking at a piano.) And, we already know the expansion for major tertia to be (9/8, 10/9). A quarta is therefore a combination of tone, minor tone, and a semitone. Let’s order the intervals this way: (minor tone, tone, semitone).

Putting all the pieces together, we can write out the octave as a list of these adjacent intervals: (9/8, 10/9, 16/15, 9/8, 10/9, 9/8, 16/15). In words: (tone, minor tone, semitone, tone, minor tone, tone, semitone). These seven intervals define an 8-note scale that divides an octave into smaller intervals. We can also express the same scale with intervals relative to the root note, instead of intervals relative to the preceding note in the sequence. To calculate it, accumulate the product of ratios in the original sequence. In this case, the ratios will be: (1, 9/8, 5/4, 4/3, 3/2, 5/3, 15/8, 2).

What we have reinvented, is the just intonation scale discovered by Claudius Ptolemy in 2nd century CE. Note that he lived 600 years after Pythagoras, who started research into scales, and in whose name we have another scale, the Pythagorean scale.

Unlike Pythagoras, who constructed a scale solely based on transpositions of quintas and octaves, Ptolemy used tertia intervals as the basis.

Note that in the Ptolemy’s scale — which became the basic scale of Western music— the second note is a tone, the fourth note is quarta, and the fifth note is quinta. This explains the American English names of “second”, “fourth”, “fifth” for those intervals.

The Ptolemy’s scale falls into the category of diatonic scales. The word diatonic is derived from Greek language, and the prefix “dia” means “through” in Greek. The idea is that the scale is mostly made out of tones, which are relatively large, pleasing, intervals. The two semitones, which are smaller and harsher intervals, are not close to each other because they are padded with at least two tones.

In contrast, a scale that has two adjacent semitones, is not diatonic because it has chromaticism. Chromatic intervals are unstable, in that the listener is expecting for them to be short lived, leading somewhere else. They could be leading to a stable, pleasing interval, or to another chromatic interval, which in turn leads elsewhere. You can hear an example of chromaticism in the Flight of the Bumblebee interlude by Rimsky-Korsakov.