Your Mobile Phone as a Gold Mine (for hedge funds)

The alarm sounds. Time to wake up.

Still bleary-eyed, you reach for your phone to check your messages. You turn the phone on. Before you know it, the tracking begins…

But this tracking is not some kind of clandestine, paranoia-inducing government surveillance operation. Rather, it’s the geolocation data that your phone’s apps such as Facebook and Instagram transmit that enable you to be tracked.

This data can represent virtually any information that’s collected by an app or service provider concerning where your phone is/was located at a certain time. From the moment you wake up to when you sleep.

Indeed, even while you sleep.

And it’s proving to be a veritable gold mine for hedge funds…

GPS = untapped alpha?

Estimates suggest there are around 2 billion smartphone users in the world. Each one of these devices is likely to contain at least a few apps that are capable of tracking its user‘s location. Apps that cover navigation, weather, shopping, and social media, for instance, are some of the most common sources of geolocation data. And even if we’re not actually using the app, geographical coordinates can still be obtained that indicate our phone’s position at any moment.

By using the phone’s GPS to send API calls to the Operating System (for example, Android), apps can determine where we are, how long we are there for, who we are with, and lots more information about our preferences and habits. They can then sell this geolocation data on to interested customers, including investment firms and digital marketers.

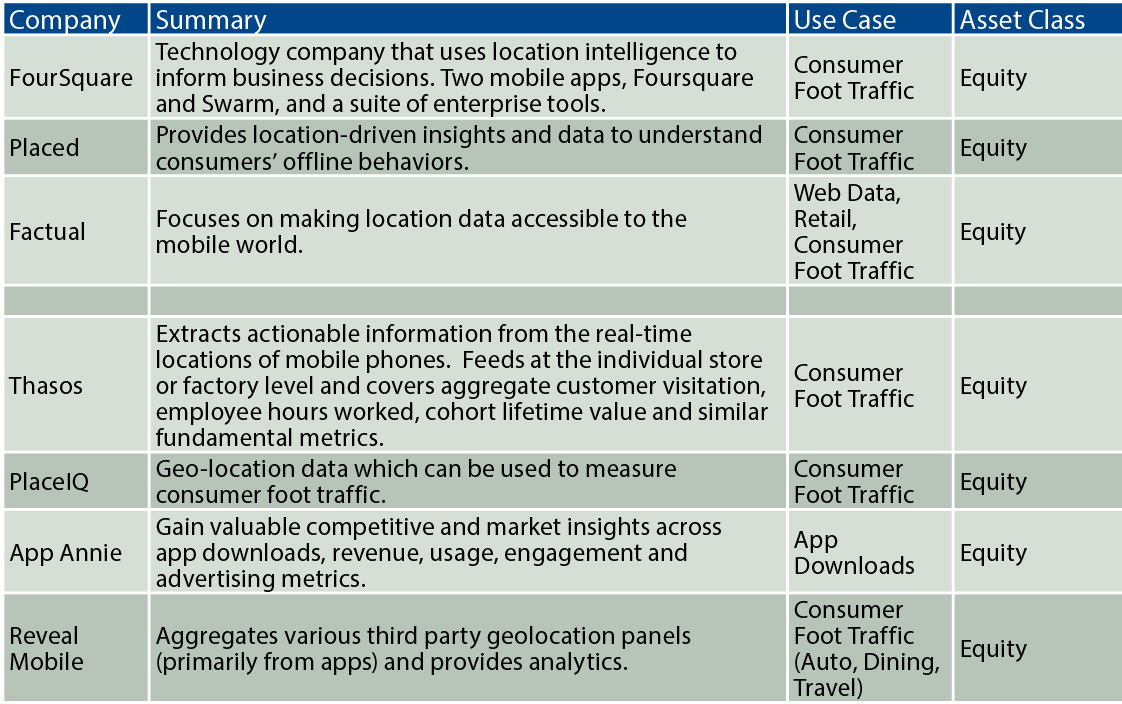

Just think of all the apps on your phone that require your location details. Uber needs it to connect you with their drivers. Fitness apps track your running routes and help to improve your overall performance. And Foursquare “uses location intelligence to build meaningful consumer experiences and business solutions.”

Hmm…

Indeed, it was Foursquare that provides what is now considered a classic example of the immense value geolocation data can possess. The company’s CEO Jeff Glueck published a Medium post that predicted ahead of time that Chipotle would see a 30% decline in its sales for Q1 2016. As the app allows its customers to check-in at the places they visit, Glueck was able to use this information to observe a declining trend in foot traffic to the Mexican fast-food restaurant’s outlets — and he did it so well ahead of the release of Chipotle’s results for the quarter which, not surprisingly, showed both heavy losses and a massive fall in sales.

Today, it’s companies like Thasos Group that have emerged as the hedge fund industry’s most highly prized geolocation data providers. The company seeks to provide “actionable information from real-time location data,” principally through its new geolocation service, Streams, which collects real-time mobile phone data pertaining to deliveries to loading docks, hours worked on assembly lines, patient counts in hospitals, foot traffic in retail businesses, and much more.

As explained by co-founder John Collins, the company gets passive raw location data from many different sources, including “when someone is up in the morning, getting ready for work, on the commute to work, at the office sitting in a conference room, at lunch, [and] on the way home picking up some groceries….” This enables the firm to obtain data from “a really rich sort of sequence of locations visited…”. To then perform the necessary analytics, Thasos has amassed a team of data scientists, engineers and financial professionals who, according to Founder and CEO Greg Skibiski, “are driving a fundamental change in the kinds of data used to make informed investment decisions.”

From the buy side’s perspective, meanwhile, those investment decisions are increasingly the result of trends extracted from raw geolocation data. Portfolio managers can now track sales at various companies, shifting demographic patterns and changes in retail trends, all of which are derived from information provided by apps and data providers like Thasos. And with potentially millions of smartphones providing this information, funds will often have a healthy sample size from which to extrapolate the data and conduct its analytics.

Take the new data-driven hedge fund Trinnacle Capital Management. Co-Founder Eric Kohlmann Kupper acknowledged last year that his firm has compiled some very powerful geolocation datasets that allows it “to see the behavior and movement of large parts of the population and that gives us a very clear picture about specific companies, but also the entire sector or an industry”. And according to a 2017 report by consultancy Greenwich Associates, over one-fifth of asset managers and hedge funds have geolocation data on their wish lists.

Invasion of the Privacy Snatchers?

But it’s not straightforward for hedge funds when it comes to acquiring geolocation data. Going forward, there are likely to be plenty of roadblocks for them to navigate to ensure that ethical use of the data is consistently (and credibly) maintained. After all, while many of us won’t mind our data being used for research, many of us also don’t necessarily want it being used by hedge funds to make a profit, or for some other unknown purposes.

At the heart of the issue is whether owners of geolocation data have been given approval by customers to make their data available for sale to third parties. In the aftermath of the Cambridge Analytica scandal, people are understandably wanting to be extra careful about safeguarding their privacy concerning issues like geolocation.

Do we really want our visits to places of worship, or to hospitals or to a support group shared? I suspect most of us don’t. Nor is it simply ordinary citizens that location data could potentially harm. Fitness apps Strava and Polar have both given away sensitive location data pertaining to the personal details of military personnel. This could have serious implications for national security.

Frederike Kaltheuner of Privacy International warned last year that hedge funds that utilize location data to inform their trading strategies have “unprecedented population-level insight about individuals’ lives, communities, and entire nations and markets”. With such potential for intrusion into our lives, therefore, anonymizing this data is likely to be a mandatory safeguard put in place in the near future.

Trinnacle’s Mr. Kupper assures that all the data his fund deals with is anonymous, “We are not just complying with US data privacy rules but also with EU and German data privacy rules, which are much stricter. So, we can never track an individual, and we don’t care about that anyway. We care about the big picture.” And Thasos’ Mr. Skibiski also reportedly confirms that its data “has been volunteered, rendered anonymous, and aggregated to ensure compliance with legal and ethical standards”.

But it is likely that data laws themselves are going to continue being tightened. For instance, the EU’s sweeping General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR), which came into effect in May, specifically considers location data as being identifiable information under “personal data”. Location data may also reveal “Sensitive Personal Data” pertaining to a person’s ethnicity; political, religious or philosophical beliefs; and health or sexual orientation, all of which GDPR deems requires special protection.

While there’s no ‘set in stone’ definition of alternative data, specific types of non-traditional datasets that are proving useful to hedge funds are certainly demonstrating what alternative data is all about. Website scraping is one type. Satellite imagery is another. Although incoming privacy laws may dampen its impact on alpha generation, geolocation data is, without a doubt, taking a lead role in this alternative data revolution.

And it seems that this type of data will continue proving its worth to hedge funds during the coming months and years. Indeed, geolocation data vendor Advan Research believes over 1,000 hedge funds will eventually incorporate geolocation datasets into their trading strategies. And that ultimately means that our mobile phones are only going to become even more precious as a source of alpha.