Seeing the World Through Facebook’s Eyes

It doesn’t require a tremendous cognitive leap to imagine the techniques of the 18th century European state being applied by 21st century companies of Silicon Valley. But where the revenue of states was tied to the measurement of land, the revenues of Facebook, Google, or Amazon, etc. is tied to the measurement of minds.

“To organize the world’s information and make it universally accessible and useful,” is simply Google’s application of forestry science to web pages, and books, and terrestrial maps, and human interest in those things.

Or consider Facebook’s mantra, “to connect the world’s people.” On its face, this statement is literally true and useful. But it’s true and useful in the manner of categorizing trees with colored nails. It’s not difficult to imagine a 17th-century Zuckerberg arguing for the adoption of that time’s other organizational inventions, like the metric system in France (“People people! Measuring everything in centimeters connects

In both the case of Google and Facebook, the very act of categorization means that all the world’s information and all the world’s connected people are more easily manipulated (for “good” or “evil”). The very act of categorizing makes that manipulation easier, just as the very act of putting a child’s toys in a plastic bin makes the toys easier to move, or categorizing a town’s ethnic population makes them easier to save or to kill, or measuring trees allows you to profit from those trees.

I mean, you could say Facebook is simply human forestry.

But what should make you raise a Spockishly curious eyebrow is how tech’s synoptic view exponentially expands upon the forestry science of 18th century Prussia.

Most obviously, Facebook , Google, or Amazon don’t need to make legible the physical layout of the world (though some are, in fact, doing that with, e.g., Google Maps and self-driving vehicles). At the end of the day there is only so much land, and that land only comes in so many shapes, and anyway nations are only so big. The physical world is a world of limited space. You could say the physical world doesn’t scale.

Rather, Facebook, Google, or Amazon need to make legible the infinite wants and desires and the infinite needs and necessaries of an infinite variety of humans. Those humans live and work in a digital space, and the digital world is a world of unlimited vistas. Where the state wants to take a vig on every human transaction for a physical thing—property, homes, capital gains, trees—technology companies want to take a vig on every human thought that leads to a transaction of any thing, whether it’s physical or otherwise.

In fact, the very idea of considering physical space misses the point. In 18th century Europe, the “what” of trees that mattered. But on 21st century Earth, it is not simply the “what” of a human that matters. It is the “how” and they “why” of how that human acts in aggregate with other humans (also in aggregate).

In one way, this is not a new observation. Who hasn’t heard, while trying to ignore junior marketing execs talking loudly in a bar, a version of the popular saying, “If you’re not paying for something, you’re not the customer; you’re the product being sold.”

But in another way, we’ve all been slow to understand that what’s being sold isn’t so much facts — i.e., the “what” of surname, birthday, hometown, etc., which marked the early search and social networks. Instead, what’s being measured and sold today is the “how” and “why” of actual decisions.

For example, consider how the Kingdom of Prussia planted their stands of trees, similar to this:

This is a repeating quincunx. You can stand at any one point and see straight lines radiating outward. Thomas Browne saw the hand of God in this pattern. Thomas Edison apparently tattooed it on his own hand (after also inventing the first electric pen, so there’s that).

In one way, you could say that Facebook, Google, or Amazon consider their data like a quincunx. Infinite rows of objects, neatly ordered in relational databases, easily legible to managers and accessible to developers for cutting or felling or experimentation.

In another way, you could also say that Facebook, Google, or Amazon consider their users in such a manner. Infinite rows of people objects, neatly ordered in relational databases, easily legible to managers and accessible to developers for cutting or felling or experimentation.

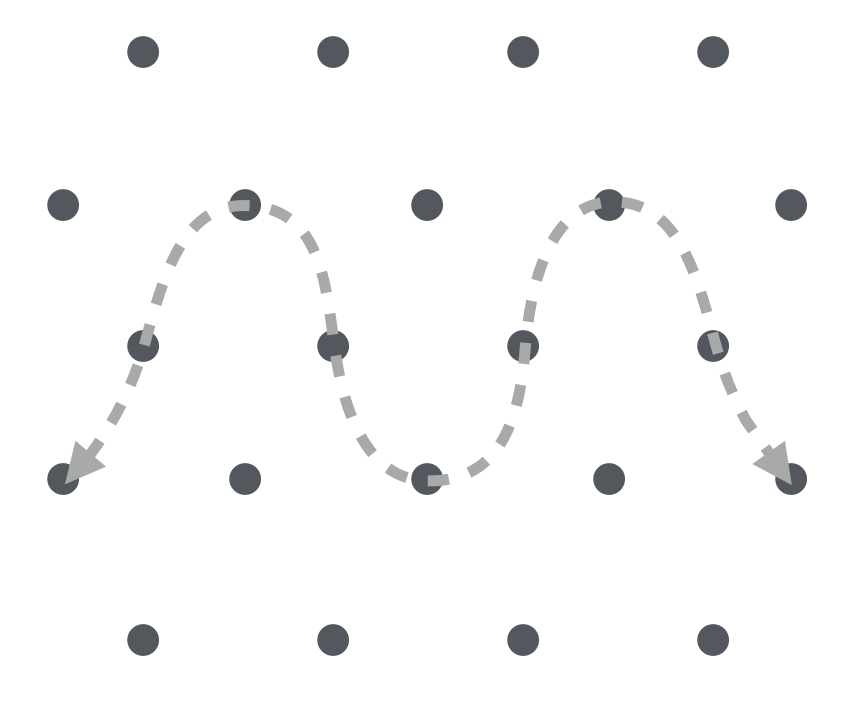

In yet another way, you could say that Facebook, Google, or Amazon also consider their users decisions like this. But decisions aren’t objects. Decisions are movements amongst and between objects, like so:

To Facebook, Google, Amazon, etc., the question began with “who” and “what.” What user, what object, what platform, etc. But eventually, these companies want to get to “why.” Why and in which categories and in what volume do people decide to click on video N, and then N + 1, and then N + 2. Or product N + 1. Or whatever.

As with measuring a forest, knowing those clicks allows a company to forecast revenues. But creating the condition of those clicks? Predicting their pathing? That’s planting a forest in the image of your own measurement technique.

Or put it like this: Predicting the growth of trees meant creating a mental model of a forest. Predicting the clicks of humans means creating a mental model of mental models.