On-Demand Workers Deserve Better

Perhaps unsurprisingly, San Francisco has a larger percentage of adults earning income from online labor platforms than other major cities. In San Francisco and New York, these workers also saw rising earnings between 2015 and 2016, even while the nationwide average income from such platforms dropped.

Looking beyond earnings, we can use turnover rates to learn more about job quality. Nationwide, more than half of online platform participants drop out within a year. San Francisco actually has the lowest dropout rate of the cities surveyed, and it still comes in at 45 percent. The same JPMorgan Chase analysis referenced above suggests people leave the gig economy because job flexibility is overshadowed by a lack of traditional benefits:

This might be because platforms as of yet do not typically offer the full package of income security, benefits, training, and income and career progression that many traditional jobs offer. By offering the flexibility to work when and wherever participants want, platforms might have difficulty creating organizational commitment, work-group cohesion, and promotion opportunities — some of the typical predictors of employee retention in traditional jobs.

Some on-demand service providers claim they plan for high turnover rates, and that their intent is simply to offer people temporary work while they seek long-term, sustainable jobs. However, we know that Uber, Lyft, and Postmates use psychological tricks to coax workers to stay on their apps and keep working.

By pitching themselves as social safety nets rather than normal employers, these on-demand service providers can say they only offer short-term, quick-cash, low-growth gigs. The narrative allows them to shirk their responsibility to take care of their employees. These platforms typically do not offer health benefits, paid time off, or professional development. Workers are given little bargaining power, and therefore, little stability.

One analysis found that the hourly wage for Uber drivers only becomes reliable when drivers work full time. As Slate puts it:

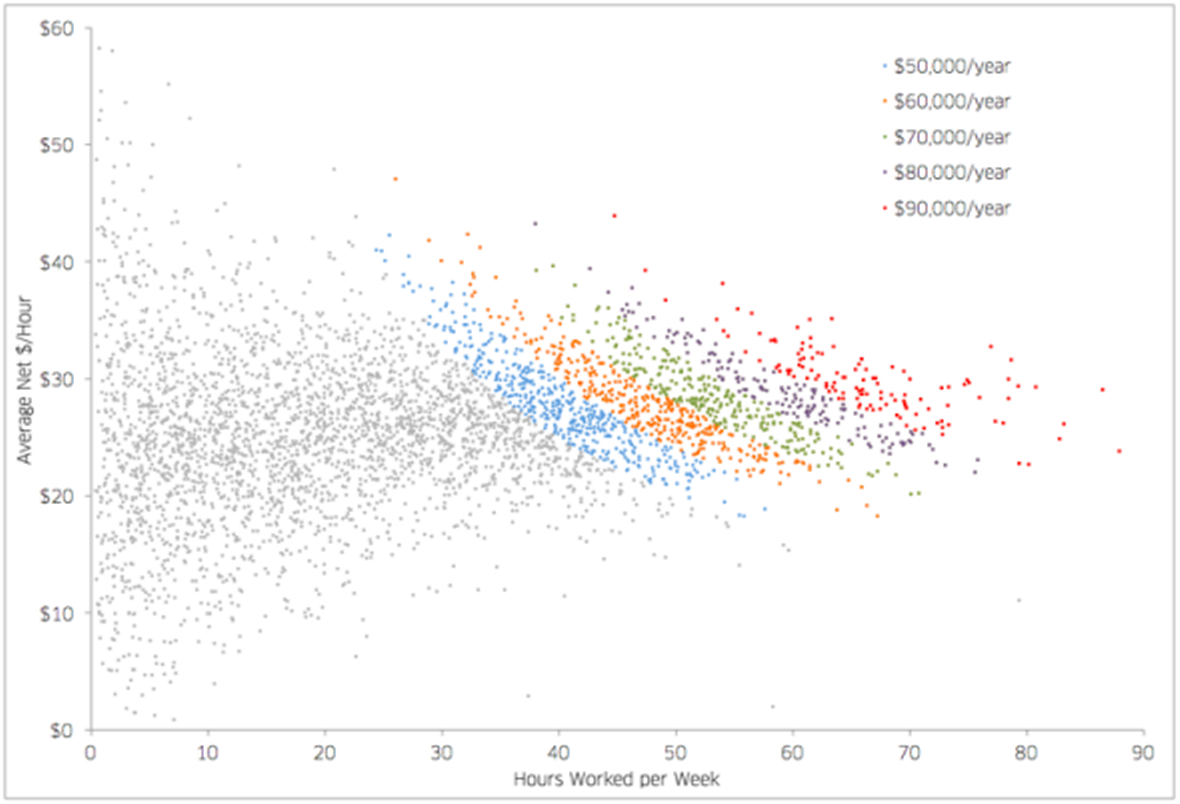

As the number of hours worked per week moves past 50 or 60, drivers start to reliably earn somewhere between $20 and $35 an hour. But for those working part time, and especially less than 30 hours, it’s a crapshoot.

This scatterplot, provided by Uber, shows us that at 40 hours a week, drivers will cap out at about $60,000 per year. Not necessarily a bad salary, though it doesn’t take gas, insurance, or car maintenance into consideration. In comparison, the median entry-level job in San Francisco pays $62,758.

On-demand service work tends to be more common and stable in high-population areas, which is also where affordable housing is less attainable. In San Francisco proper, median home prices are above $1 million. Even in the greater Bay Area, the median home price as of July was around $850,000 — clearly not affordable on a $60,000 income.

What can we do to protect this vulnerable class of workers?

- Include them in labor laws and require that companies treat contractors and full-time workers equally. (Or at the very least, stop incentivizing companies to switch to a part-time labor force.)

- Create a nationwide fund that requires platforms to pay into portable benefits that move with workers as they change gigs.

- Petition for more housing across the Bay Area — construction zones can be changed by legislation, and prices will naturally decrease as supply increases.

- Build a high-speed commuting system to link the metropolitan areas of the Bay to more affordable housing, leading to the “democratization of geography.”

- Redefine how we view on-demand workers. For some reason, it seems we feel less obligated to tip these workers, although we wouldn’t hesitate in a dining environment. Let’s treat them with the same basic level of respect and appreciation we would other service workers.