This is how Big Oil will die

It’s 2025, and 800,000 tons of used high strength steel is coming up for auction.

The steel made up the Keystone XL pipeline, finally completed in 2019, two years after the project launched with great fanfare after approval by the Trump administration. The pipeline was built at a cost of about $7 billion, bringing oil from the Canadian tar sands to the US, with a pit stop in the town of Baker, Montana, to pick up US crude from the Bakken formation. At its peak, it carried over 500,000 barrels a day for processing at refineries in Texas and Louisiana.

But in 2025, no one wants the oil.

The Keystone XL will go down as the world’s last great fossil fuels infrastructure project. TransCanada, the pipeline’s operator, charged about $10 per barrel for the transportation services, which means the pipeline extension earned about $5 million per day, or $1.8 billion per year. But after shutting down less than four years into its expected 40 year operational life, it never paid back its costs.

The Keystone XL closed thanks to a confluence of technologies that came together faster than anyone in the oil and gas industry had ever seen. It’s hard to blame them — the transformation of the transportation sector over the last several years has been the biggest, fastest change in the history of human civilization, causing the bankruptcy of blue chip companies like Exxon Mobil and General Motors, and directly impacting over $10 trillion in economic output.

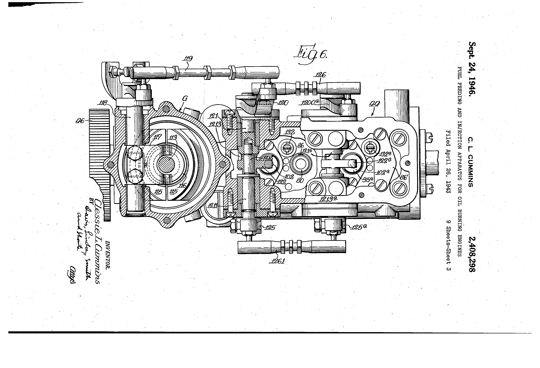

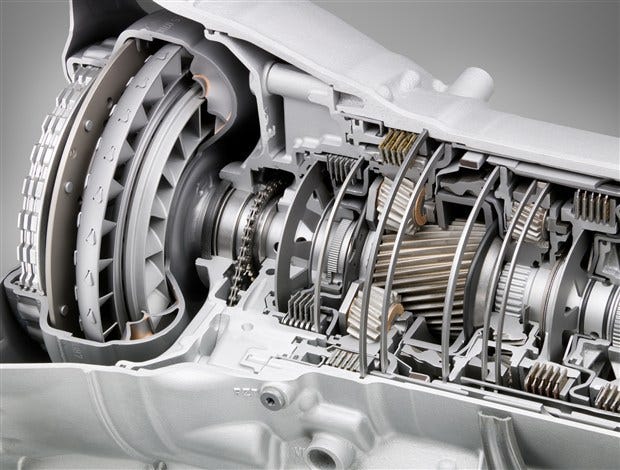

And blame for it can be traced to a beguilingly simple, yet fatal problem: the internal combustion engine has too many moving parts.

Let’s bring this back to today: Big Oil is perhaps the most feared and respected industry in history. Oil is warming the planet — cars and trucks contribute about 15% of global fossil fuels emissions — yet this fact barely dents its use. Oil fuels the most politically volatile regions in the world, yet we’ve decided to send military aid to unstable and untrustworthy dictators, because their oil is critical to our own security. For the last century, oil has dominated our economics and our politics. Oil is power.

Yet I argue here that technology is about to undo a century of political and economic dominance by oil. Big Oil will be cut down in the next decade by a combination of smartphone apps, long-life batteries, and simpler gearing. And as is always the case with new technology, the undoing will occur far faster than anyone thought possible.

To understand why Big Oil is in far weaker a position than anyone realizes, let’s take a closer look at the lynchpin of oil’s grip on our lives: the internal combustion engine, and the modern vehicle drivetrain.

Cars are complicated.

Behind the hum of a running engine lies a carefully balanced dance between sheathed steel pistons, intermeshed gears, and spinning rods — a choreography that lasts for millions of revolutions. But millions is not enough, and as we all have experienced, these parts eventually wear, and fail. Oil caps leak. Belts fray. Transmissions seize.

To get a sense of what problems may occur, here is a list of the most common vehicle repairs from 2015:

- Replacing an oxygen sensor — $249

- Replacing a catalytic converter — $1,153

- Replacing ignition coil(s) and spark plug(s) — $390

- Tightening or replacing a fuel cap — $15

- Thermostat replacement — $210

- Replacing ignition coil(s) — $236

- Mass air flow sensor replacement — $382

- Replacing spark plug wire(s) and spark plug(s) — $331

- Replacing evaporative emissions (EVAP) purge control valve — $168

- Replacing evaporative emissions (EVAP) purging solenoid — $184

And this list raises an interesting observation: None of these failures exist in an electric vehicle.

The point has been most often driven home by Tony Seba, a Stanford professor and guru of “disruption”, who revels in pointing out that an internal combustion engine drivetrain contains about 2,000 parts, while an electric vehicle drivetrain contains about 20. All other things being equal, a system with fewer moving parts will be more reliable than a system with more moving parts.

And that rule of thumb appears to hold for cars. In 2006, the National Highway Transportation Safety Administration estimated that the average vehicle, built solely on internal combustion engines, lasted 150,000 miles.

Current estimates for the lifetime today’s electric vehicles are over 500,000 miles.

The ramifications of this are huge, and bear repeating. Ten years ago, when I bought my Prius, it was common for friends to ask how long the battery would last — a battery replacement at 100,000 miles would easily negate the value of improved fuel efficiency. But today there are anecdotal stories of Prius’s logging over 600,000 miles on a single battery.

The story for Teslas is unfolding similarly. Tesloop, a Tesla-centric ride-hailing company has already driven its first Model S for more 200,000 miles, and seen only an 6% loss in battery life. A battery lifetime of 1,000,000 miles may even be in reach.

This increased lifetime translates directly to a lower cost of ownership: extending an EVs life by 3–4 X means an EVs capital cost, per mile, is 1/3 or 1/4 that of a gasoline-powered vehicle. Better still, the cost of switching from gasoline to electricity delivers another savings of about 1/3 to 1/4 per mile. And electric vehicles do not need oil changes, air filters, or timing belt replacements; the 200,000 mile Tesloop never even had its brakes replaced. The most significant repair cost on an electric vehicle is from worn tires.

For emphasis: The total cost of owning an electric vehicle is, over its entire life, roughly 1/4 to 1/3 the cost of a gasoline-powered vehicle.

Of course, with a 500,000 mile life a car will last 40–50 years. And it seems absurd to expect a single person to own just one car in her life.

But of course a person won’t own just one car. The most likely scenario is that, thanks to software, a person won’t own any.