Organisational Agility: Give People a VOICE

Organisational Agility: Give People a VOICE

Don’t Mandate One Way™.

“You are special, you are a beautiful and unique snowflake”

You are, your team is and so are the complex adaptive systems that you are part of.

This is the third article in a series, sharing a number of observed antipatterns and corresponding patterns

We are entering a new Deployment Period in a 50 year cycle, in the Age of Digital, as well articulated by Carlota Perez in ‘Technological Revolutions and Financial Capital’.

Traditional organisations need to adopt new ways of working in order to survive and thrive, to leverage the on-demand compute, information and communication power which is in the cloud and in our pockets, to keep up with competitors and challengers, and to delight customers. Today, for

The antipatterns and patterns are based on lessons learnt through doing, including learning from failing. We have been servant leaders on better ways of working, applying agile, lean, DevOps, design thinking, systems thinking and so on, across a large (80,000 people), old (300+ years old), global, not-born-agile, highly regulated enterprise. I have been delivering change with an agile mindset, principles and practices since the early 1990s, about a decade prior to the Agile Manifesto, when the term ‘lightweight processes’ was used. The antipatterns and patterns are also based on learnings from the community, from other horses, rather than unicorns, on similar journeys.

Antipattern: Golden Hammer

The mandating of one set of prescriptive practices, organisation-wide, is often combined with the capital A Agile and capital T Transformation antipatterns. The Golden Hammer antipattern was summed up by Abraham Maslow in 1966 who said, “I suppose it is tempting, if the only tool you have is a hammer, to treat everything as if it were a nail”. Herein lie two antipatterns: (1) Golden and (2) Hammer.

Antipattern part 1: Golden

Mandating any one set of practices on people and teams is an antipattern.

“Imposing a process on a team is completely opposed to the principles of agile, and has been since its inception. A team should choose its own process — one that suits the people and context in which they work. Imposing an agile process from the outside strips the team of the self-determination which is at the heart of agile thinking. Not only should a team choose their own process, the team should be in control of how that process evolves.”, Martin Fowler, 2006 (source)

The Agile Manifesto emphasises individuals and interactions over processes and tools, collaboration over contract negotiation, motivated individuals who are given support and trusted to get the job done, self organising teams regularly reflecting on how to be more effective, tuning and adjusting their behaviour, practices and processes.

“With so many differences, how can we say there’s one way that’s going to work for everybody? We can’t. And yet what I’m hearing so much is the Agile Industrial Complex imposing methods upon people, and that to me is an absolute travesty. I was gonna say “tragedy”, but I think “travesty” is the better word because there is no one-size-fits-all. ”, Martin Fowler, Agile Australia 2018 (source)

Unfortunately, it is common at the moment to see prescriptive processes being mandated across teams and across organisations. This should not be done. Inflicting capital ‘A’ Agile is not empowering, it does not show respect for people, it drives fear and resistance and it is not taking an agile approach to agility. It moves the locus of control to be external, reducing psychological ownership and intrinsic motivation.

Perhaps this is not surprising where many leaders in large, traditional firms have got to where they’ve got to with a reductionist, predictive, command & control mindset. This gives rise to the Agile Industrial Complex. An old ways of working view is being applied to new ways of working. In some cases, it may take a new generation of leaders.

“Knowledge workers themselves are best placed to make decisions about how to perform their work”, Peter F. Drucker

Antipattern part 2: Hammer

There is no one-size-fits-all for organisational agility. There is no One Way™ that optimises outcomes in all contexts.

Your organisation, your customers, your value propositions, your environment, your processes, your system of work, your leaders, your teams, your constraints, your starting point, your behavioural norms, your heritage, your brand, your team and you, are unique.

“If the path ahead is clear, you’re on someone else’s path”, Joseph Campbell

Organisations are heterogeneous, not homogeneous. Organisations are emergent, not predictive. Organisations are complex adaptive systems.

“A complex adaptive system is a dynamic networks of interactions, their relationships are not aggregations of the individual static entities, i.e., the behavior of the ensemble is not predicted by the behavior of the components. They are adaptive in that the individual and collective behavior mutate and self-organize corresponding to the change-initiating event.” Wikipedia (source)

Growing agility (rather than scaling capital ‘A’ Agile) enterprise-wide is about leveraging that complexity, diversity and emergence, not inflicting sameness on every team. The approach to organisational agility cannot be cookie-cutter.

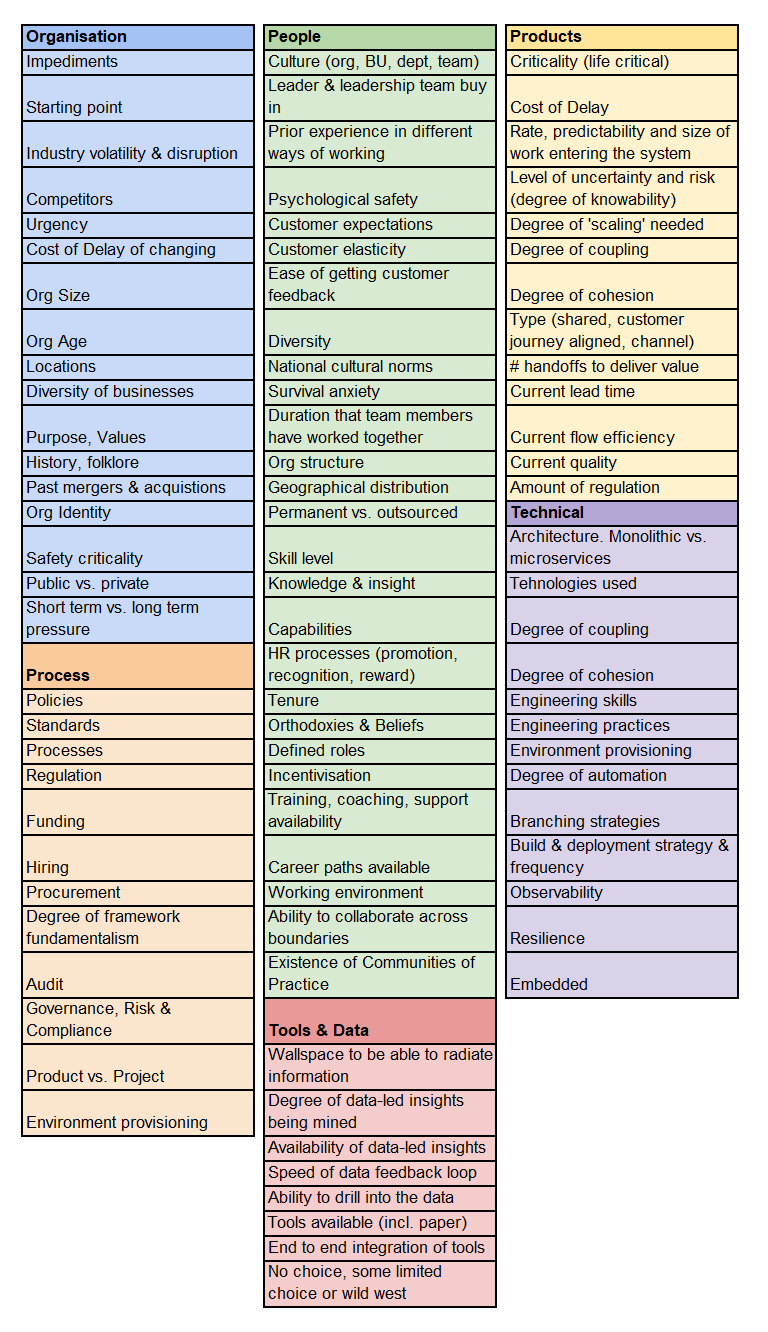

Your context is unique. To illustrate this point, here are some of the factors that make up your context:

It is interesting to note that the People category has the most contextual criteria and Tooling the least, reinforcing how much this is about people.

It was a quick exercise to brainstorm these contextual criteria and it surprised me that as many as 90 criteria emerged in a short amount of time. This is 1.2 x 10²⁷ (1.2 octillion) unique combinations of the criteria, assuming the criteria are binary, which they aren’t, there are many more combinations. Clearly, your context is unique and across a large organisation there are many unique contexts, like fingerprints. And your context is changing. And that pace of change is getting faster.

There are two contextual criteria in particular that I’d like to call out. Scaling Agile and Culture.

Scaling Agile can have many interpretations and meanings, from a handful of teams on one large product with dependencies not broken, all the way to the diversity and complexity of organisation-wide agility with thousands of value streams, teams and contexts. Depending on why you want to ‘Scale Agile’ and what you mean by ‘Scaling Agile’, your approach will differ.

Understanding the Incumbent Culture is key. Within one large organisation there will likely be a number of separate prevalent cultures, due to history, folklore, location, leadership style and so on. It would be foolish to take one approach across different cultures. There are many cultural models to use as a guide. Take Westrum’s typology as one example. If the starting culture is Pathological, then psychological safety will be thin on the ground. An autocratic culture is prevalent and in the worst cases there is a culture of fear with learned helplessness. I’ve spoken to teams who didn’t dare to inspect and adapt. A revolutionary approach to changing ways of working is not likely to be successful in this context. I have seen it fail with the imposition of Scrum and synchronised Sprints, which was a case of inflicting revolution in an environment with a lack of safety. A better approach in this context is inviting evolution over imposing revolution, starting with what you do now, for reasons I go into below.

“The level of consciousness of an organisation cannot exceed the level of consciousness of its leader”, Frederic Laloux

If the starting culture is Generative, if there is psychological safety, if there are already pockets of mastery, if there is strong survival anxiety with a high cost of delay, then it is possible that inviting revolutionary change is preferable in this context.

Frameworks

The challenge for any framework of practices in an emergent context is the balancing line between prescription for beginners and flexibility as people gain mastery. A framework either explicitly caters to adaptability to context by not being prescriptive on practices, shining a light on the problems and letting people work out how to solve them, or it is prescriptive and dogmatic. In the latter case as mastery grows you can treat the framework as a departure point and inspect & adapt away from it, so it is no longer being ‘done’, if that improves your outcomes.

Scrum and its scaled variants such as SAFe, LeSS, Nexus and [email protected], are revolutionary rather than evolutionary as they introduce new roles, artifacts, events and rules. The new roles, artifacts and events are non-negotiable. You’re either doing it or you’re not doing it. The scaled variants have evolved in in a context of scaling vertically, many teams on one large product, with dependencies. Disciplined Agile supports context sensitive choice with guidance. It suits the context of enterprise agility and scaling horizontally, catering to diversity and emergence, with guardrails. The Kanban Method is evolutionary, you apply it to your process, it shines a light on flow and impediments to flow. More on this topic in a subsequent post.

All are useful tools to have in the toolbox. One size does not fit all.