Android Architecture Patterns Part 3: Model

Android Architecture Patterns Part 3:

Model-View-ViewModel

After four different designs in the first six months of the development of the upday app, we learned one important lesson: we need an architecture pattern that allows fast reaction to design changes! The solution we chose in the end was Model-View-ViewModel. Discover with me what MVVM is; how we are applying it at upday and what makes it so perfect for us.

The Model-View-ViewModel Pattern

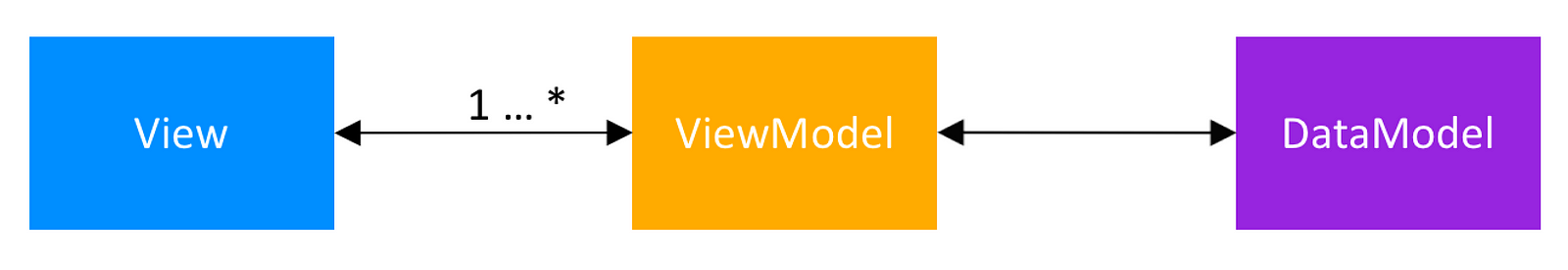

The main players in the MVVM pattern are:

- The View — that informs the ViewModel about the user’s actions

- The ViewModel — exposes streams of data relevant to the View

- The DataModel — abstracts the data source. The ViewModel works with the DataModel to get and save the data.

At a first glance, MVVM seems very similar to the Model-View-Presenter pattern, because both of them do a great job in abstracting the view’s state and behavior. The Presentation Model abstracts a View independent from a specific user-interface platform, whereas the MVVM pattern was created to simplify the event driven

If the MVP pattern meant that the Presenter was telling the View directly what to display, in MVVM, ViewModel exposes streams of events to which the Views can bind to. Like this, the ViewModel does not need to hold a reference to the View anymore, like the Presenter is. This also means that all the interfaces that the MVP pattern requires, are now dropped.

The Views also notify the ViewModel about different actions. Thus, the MVVM pattern supports two-way data binding between the View and ViewModel and there is a many-to-one relationship between View and ViewModel. View has a reference to ViewModel but ViewModel has no information about the View. The consumer of the data should know about the producer, but the producer — the ViewModel — doesn’t know, and doesn’t care, who consumes the data.

Model-View-ViewModel at upday

A quick look at the Android posts on the upday blog will instantly reveal what our favorite library is: RxJava. So it’s no wonder, because RxJava is the backbone of upday’s code! The event driven part required by MVVM is done using RxJava’s Observables. Here’s how we apply MVVM in the Android app at upday, with the help of RxJava:

DataModel

The DataModel exposes data easily consumable through event streams — RxJava’s Observables. It composes data from multiple sources, like the network layer, database or shared preferences and exposes easily consumable data to whomever needs it. The DataModels hold the entire business logic.

Our strong emphasis on the single responsibility principle leads to creating a DataModel for every feature in the app. For example, we have an ArticleDataModel that composes its output from the API service and database layer. This DataModel handles the business logic ensuring that the latest news from the database is retrieved, by applying an age filter.

ViewModel

The ViewModel is a model for the View of the app: an abstraction of the View. The ViewModel retrieves the necessary data from the DataModel, applies the UI logic and then exposes relevant data for the View to consume. Similar to the DataModel, the ViewModel exposes the data via Observables.

We learned two things about the ViewModel the hard way:

- The ViewModel should expose states for the View, rather than just events. For example, if we need to display the name and the email address of a

User, rather than creating two streams for this, we create aDisplayableUserobject that encapsulates the two fields. The stream will emit every time the display name or the email changes. This way, we ensure that our View always displays the current state of theUser. - We should make sure that every action of the user goes through the ViewModel and that any possible logic of the View is moved in the ViewModel.

We wrote about these two topics in a blog post about common mistakes in MVVM + RxJava.

View

The View is the actual user interface in the app. It can be an Activity, a Fragment or any custom Android View. For Activities and Fragments, we are binding and unbinding from the event sources on onResume() and onPause().

private final CompositeSubscription mSubscription = new CompositeSubscription();

@Override

public void onResume() {

super.onResume();

mSubscription.add(mViewModel.getSomeData()

.observeOn(AndroidSchedulers.mainThread())

.subscribe(this::updateView,

this::handleError));

}

@Override

public void onPause() {

mSubscription.clear();

super.onPause();

}If the MVVM View is a custom Android View, the binding is done in the constructor. To ensure that the subscription is not preserved, leading to possible memory leaks, the unbinding happens in onDetachedFromWindow.

private final CompositeSubscription mSubscription = new CompositeSubscription();

public MyView(Context context, MyViewModel viewModel) {

...

mSubscription.add(mViewModel.getSomeData()

.observeOn(AndroidSchedulers.mainThread())

.subscribe(this::updateView,

this::handleError));

}@Override

public void onDetachedFromWindow() {

mSubscription.clear();

super.onDetachedFromWindow();

}

}

Testability Of The Model-View-ViewModel Classes

One of the main reasons why we love the Model-View-ViewModel pattern is that it is so easy to test.

DataModel

The use of inversion of control pattern, heavily applied in our code, and the lack of any Android classes, facilitate the implementation of unit tests of the DataModel.

ViewModel

We see the Views and the unit tests as two different types of consumers of data from the ViewModel. The ViewModel is completely separated from the UI or any Android classes, therefore straightforward to unit test.

Consider the following example where the ViewModel just exposes some data from the DataModel:

public class ViewModel {

private final IDataModel mDataModel;public ViewModel(IDataModel dataModel) {

mDataModel = dataModel;

}public Observable<Data> getSomeData() {

return mDataModel.getSomeData();

}

}The tests for the ViewModel are easy to implement. With the help of Mockito, we are mocking the DataModel and we control the returned data for the methods used. Then, we make sure that when we subscribe to the Observable returned by getSomeData(), the expected data is emitted.

public class ViewModelTest {@Mock

private IDataModel mDataModel;

private ViewModel mViewModel;

@Before

public void setUp() throws Exception {

MockitoAnnotations.initMocks(this);

mViewModel = new ViewModel(mDataModel);

}

@Test

public void testGetSomeData_emitsCorrectData() {

SomeData data = new SomeData();

Mockito.when(mDataModel.getSomeData())

.thenReturn(Observable.just(data));

TestSubscriber<SomeData> testSubscriber =

new TestSubscriber<>();

mViewModel.getSomeData().subscribe(testSubscriber);

testSubscriber.assertValue(data);

}

}

If the ViewModel needs access to Android classes, we create wrappers that we call Providers. For example, for Android resources we created a IResourceProvider, that exposes methods like String getString(@StringRes final int id). The implementation of the IResourceProvider will contain a reference to the Context but, the ViewModel will only refer to an IResourceProvider injected.

As we have mentioned above, and in our common mistakes blog post, we are creating model objects to hold the state of the data. This also allows a higher degree of testability and control of the data that is emitted by the ViewModel.

View

Given that the logic in the UI is minimal, the Views are easy to test with Espresso. We are also using libraries like DaggerMock and MockWebServer to improve the stability of our UI tests.

Is MVVM The Right Solution?

We have been using MVVM together with RxJava for almost a year now. We have seen that since the View is just a consumer of the ViewModel, it was easy to just replace different UI elements, with minimal, or sometimes zero changes in other classes.

We have also learned how important separation of concerns is and that we should split the code more, creating small Views and small ViewModels that only have specific responsibilities. The ViewModels are injected in the Views. This means that most of the times, we just add the Views in the XML UI, without doing any other changes. Therefore, when our UI requirements change again, we can easily replace some Views with new ones.

Conclusion

MVVM combines the advantages of separation of concerns provided by MVP, while leveraging the advantages of data bindings. The result is a pattern where the model drives as many of the operations as possible, minimizing the logic in the view.

After the design changes during the “infancy” of our app, we switched to MVVM in upday’s “adolescence” — a period of mistakes from which we learned a lot. Now, we can be proud of an app that has proven its resistance to another redesign. We are finally close to being able to call upday a mature app.

A simple example of the MVVM implementation can be found here.A “Hello, World!” comparison between MVP and MVVM can be found here. Check out also our post on Model-View-Presenter.