Want to get DNA tested? A Privacy Guide

Key privacy risks and some other things to consider before you spit in a tube:

- Genetic discrimination,

- Re-identification of anonymized data,

- Skewed research benefits,

- Compromised family privacy,

- Law enforcement access to genetic data,

- Variable control over genetic data deletion.

Genetic data is unique in that it is immutable — unlike your name, gender, or credit card number, your DNA can’t be changed (Note:

Many genetic testing companies share data with third parties for research purposes and when law enforcement compels them to do so. Recently, in response to increasing concerns about genetic data privacy, major DTC genetic testing companies (23andMe, Ancestry, Helix, MyHeritage, & Habit) committed to a set of voluntary

However, even when you expressly consent to share your anonymized genetic data with third parties or voluntarily upload your genetic profile to a public database, it’s important to understand that anonymized data can be cross-referenced with other databases to re-identify you and/or your family members.

And if you don’t want your genetic data shared or public, understand that when you hand over your DNA to a company, you are entrusting it to keep your data both secure and private. (Note: Nearly all DTC genetic testing companies retain the right to change their privacy policies at any time, often without notice.) In cases where the security of the data and/or your privacy are compromised, you should know what kinds of risks you face and what protections may or may not apply.

Risk #1: Genetic Discrimination

Genetic discrimination occurs when you are treated differently by employers, insurance companies, schools, and other entities based on the differences in your DNA that increase your chances of developing certain diseases. According to the Council for Responsible Genetics, there are hundreds of documented cases of genetic discrimination. While the extent to which genetic discrimination occurs is debated, there is a clear history of genetic discrimination in the United States (notably, the eugenics movement).

Today, GINA, the Genetic Information Nondiscrimination Act (2008), prohibits genetic discrimination from employers and health insurance companies. However, this federal law excludes other forms of insurance (e.g., life and disability insurance) and does not apply to schools, mortgage lending, or housing.

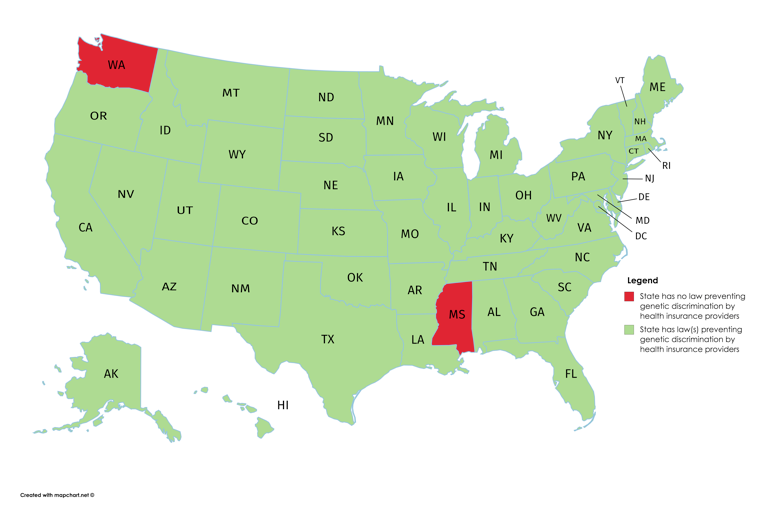

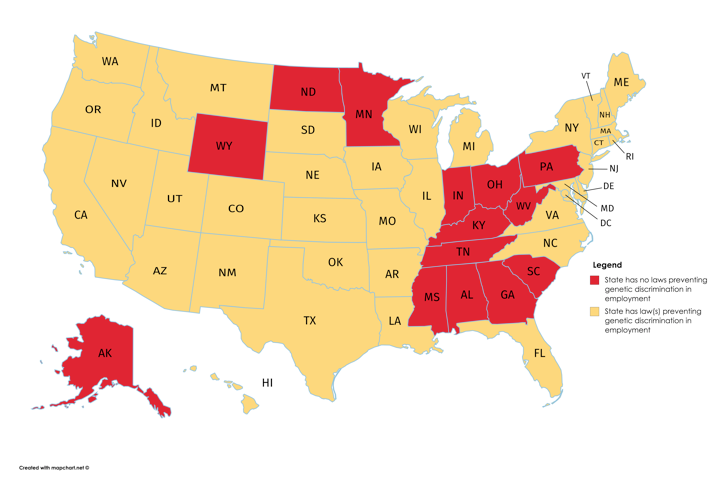

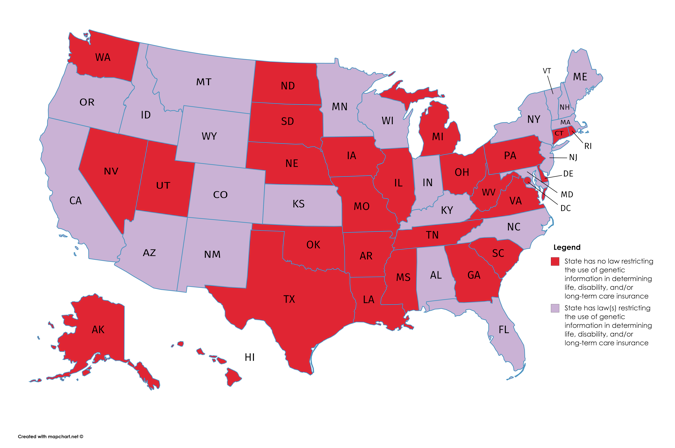

Though state laws protecting against genetic discrimination exist, they vary widely in scope, applicability, and amount of protection provided. (The NHGRI Genome Statute and Legislation Database has a full list of state statutes and bills introduced from 2007–2018, which were used to create the maps below.)

Presently, 48 states and the District of Columbia have passed laws preventing genetic discrimination in health insurance providers.

36 states and the District of Columbia prohibit genetic discrimination in employment.

22 states and the District of Columbia prohibit genetic discrimination in life, disability, and/or long-term care insurance.

While most states have genetic information nondiscrimination laws that are commensurate with federal law, states vary in how extensively they prohibit genetic discrimination beyond health insurance and employment.

California is one state that has notably pushed for a more extensive law. In 2011, it passed CalGINA, the California Genetic Information Nondiscrimination Act, amending the Unruh Civil Rights Act, which now provides protection against genetic discrimination in employment, housing, mortgage lending, education, and participation in any activity or program that involves state funding.

However, the existence of laws protecting against genetic discrimination does not entirely preclude it. In 2012, a 15-year old boy in Palo Alto, California was removed from his school because he had genetic markers for cystic fibrosis. (The student never developed cystic fibrosis). His parents sued the school district under the American Disabilities Act (ADA). GINA did not apply to this case although genetic information was used to discriminate against the student because the case did not involve employers or health insurance. While it is unclear why a claim under CalGINA was not set forth, it’s worth noting that a violation of the ADA is itself a violation of the Unruh Civil Rights Act.

Risk #2: Re-identification of Pseudonymized Data

While DTC genetic testing companies de-identify or pseudonymize all genetic data shared with third parties (removing or replacing identifiers), third parties with access to other databases can easily cross-reference data to re-identify individuals. Re-identification risk is especially pertinent to genetic data, because genetic data cannot be truly anonymized without it losing its value to researchers (anonymization typically involves aggregation, so it can be done, but it makes the data pretty useless). There is a separate argument that genetic data cannot “truly” be de-identified or pseudonymized because it is inherently identifiable.

For certain groups, the risk of re-identification is greater.

Recently, in response to outcry about third parties’ dubious data sharing practices and concerns about the scientific merit of many health & wellness apps, 23andMe shut down third party access to its anonymized data through its API. However, 23andMe and other major DTC genetic testing companies continue to share data with many companies and research institutions, and consequently, the privacy risks that come from sharing data with third parties still remain (when the user expressly consents to share data). Once data is transferred over to third parties, risks of data breach and improper use increase, also increasing risks of re-identification.

Furthermore, while established industry leaders generally have pretty comprehensive policies on how your genetic data will be collected, used, and shared with third parties, these policies are the exception, not the norm. And according to a recent survey of DTC genetic testing companies, even amongst these industry leaders, “no company provided a specific or exhaustive list of third parties with whom data would be shared and very few elaborated on the protocols in place [to] de-identify, aggregate, or secure genetic data.”

Risk #3: Skewed Research Benefits

While volunteering to share your data with researchers can advance scientific research, be aware that DTC genetic testing companies are making large profits from the genetic data that its customers volunteer. This essentially means that genetic testing companies are getting a 2 for 1 deal: the company provides genetic testing, and in return, it not only gets your money, but also amasses a huge dataset it can sell to third parties. As one example, the multi-billion dollar British pharmaceutical company GlaxoSmithKline (GSK) recently bought $300 million in equity in 23andMe in exchange for access to 23andMe’s database of genetic information.

23andMe’s current policy specifies that individuals “acquire no rights in any research or commercial products that may be developed by 23andMe or its collaborating partners.”

This means that the individuals who paid to donate their data to researchers will likely not be compensated for their donations in the future. While people generally want to share their data when it is used for social good, sharing data does not necessarily mean it will benefit the public equitably. For example, given that the U.S. government doesn’t regulate drug prices, lots of people — data donors included — will likely be priced out of drug discoveries made with these data donations in the future.

It’s also important to consider how DTC genetic testing data impacts the scientific research conducted, and who this research truly benefits. While the price of genetic testing has decreased dramatically over the past decade, many people still cannot afford a non-medically necessary $50–100 test. The research GSK and other research institutions/companies conduct will be based on non-nationally representative samples, which could limit the applicability of its findings towards middle and upper class people. This reinforces the issue of inequitable research benefits.

Note: This doesn’t mean that genetic data sharing won’t lead to beneficial scientific advancement, and this point isn’t just applicable to genetic data sharing — it touches upon on issues with the data sharing economy as a whole— a topic that deserves a separate discussion.

Risk #4: Compromised Family Privacy

When you share your genetic data with friends, researchers, or on a public database, be aware that you’re also sharing information about your family members’ genetic code even if they haven’t consented.

While sensitive health information about yourself and your family members’ health is protected by medical privacy laws within the confines of a doctor’s office, internet genealogies and genetic information uploaded onto a public database are not. Similarly, if the researchers or third parties you opted to share your data with do not take adequate privacy and security measures, you are potentially exposing family members to privacy risks. This means that even if you aren’t concerned about re-identification or genetic discrimination, your actions may implicate others who are.

While finding out that you are predisposed to or a carrier for a genetic disease may help a family member take proactive health measures, this benefit needs to be balanced against the potential to violate others’ privacy. Family members may have personal health information exposed to employers, advertisers, and insurers, and become subject to discrimination, unwanted targeted advertising, and/or dignitary harms.

There’s also the real concern of a genetic test leading to unanticipated or unwanted information. While genetic testing can reunite families, there are also many examples of families falling apart due someone finding out their dad isn’t their biological dad.

Risk #5: Law Enforcement Access to Genetic Data

Compromised family privacy is especially relevant to law enforcement’s increasing use of genetic data. In May 2018, investigators cracked the decades-old Golden State Killer case using the genealogy website GEDMatch, an open source genetic database, on which individuals voluntarily upload their genetic profiles. The investigators first subpoenaed the company FamilyTreeDNA to identify a DNA match (false lead), then created a fake profile on GEDMatch and uploaded the killer’s DNA, identifying his 3rd and 4th cousins. They eventually identified the killer himself, Joseph James DeAngelo, a 72-year old man who had killed a least a dozen people and raped many more.

The use of genetic data in criminal investigations has the power to exonerate the innocent and incriminate the guilty. While the Golden State Killer case was a victory for DeAngelo’s victims, public safety, and law enforcement, it also raises concerns about the extent to which companies can protect your genetic data. Even if you do not upload your genetic test results to a public database, every major DTC genetic testing company’s privacy policy states that it will hand over your DNA to law enforcement if compelled to do so.

This means that you and your family members could become implicated in criminal investigations, without your consent. As long as at least one genetic relative’s DNA is stored in a database, it is highly likely that this information can be used to identify another. While it is worth noting that major companies have turned down law enforcement requests in the past (In 2017, 23andMe received and turned down 5 requests; Ancestry received 34 and turned down 3) and have agreed to “attempt to notify” individuals if their data is requested (unless they are blocked by court gag order), they also state that they will share data with law enforcement if required by law.

All states and the federal government already maintain DNA databases, with 29 states and the federal government collecting and storing the DNA not only of individuals who have been convicted, but also of those who have been arrested, but not yet convicted. While there are strict rules governing which DNA samples are included in the FBI’s national database, there are no state or federal regulations governing police departments’ private databases. While all states have some process for deleting DNA profiles if a charge is dropped or the individual is acquitted, most states require the individual to initiate the process.

You may be thinking: “As long as I’m innocent, who cares if law enforcement has my DNA or can track me and my relatives through public and private databases? Bringing criminals to justice is good!”

However, this requires the assumption that genetic profiling always produces accurate results, which is unfortunately false. Law enforcement finding a “DNA match” doesn’t always mean that they have the right suspect. Samples can be contaminated or matches can be inaccurate. Accuracy is determined by probabilities — with a key factor being how many locations (loci) in the DNA are examined. As more loci are examined, the match probability decreases. (An analogy: many lottery tickets will match at least 1 number on the winning lottery ticket, but the chances of tickets matching all numbers is incredibly small; the more numbers examined, the match probability decreases.)

A couple of examples:

- In 2003, John Puckett, a 72-year old man from California, was tried and convicted of first-degree murder by a jury who had been given incomplete information about the tested DNA sample. The jurors were told that only 1 in 1.1 million people carried the DNA markers shared by Puckett and the tested DNA sample. However, jurors were not told that Puckett had been selected via a nonrandom trawl through a police database, that the probability of a match in the database searched was 33%, and that 2 other people in the area likely matched the same evidence.

- In 2011, Adam Scott, a British man from Devon, was wrongfully charged with raping a woman 200 miles away in Manchester based on a contaminated DNA profile that matched his own. The forensic scientist who processed his sample stated a 1 in a billion chance that the matching DNA sample came from someone else unrelated to Scott. A subsequent investigation demonstrated that the DNA samples had been accidentally contaminated, and that Scott had been wrongfully charged.

Again, use of genetic data to assist law enforcement can be beneficial — privacy concerns pertain to wrongful or inaccurate use of genetic data in law enforcement decisions.

Risk #6: Challenges with Genetic Data Deletion

Lastly, it’s just really hard to delete your genetic data. While many companies have altered their privacy policies to improve and clarify data ownership and deletion rights for their consumers, a few things make it difficult to truly erase all traces of your genetic profile once you’ve shared it.

Many companies have a default policy of storing your genetic data indefinitely: A survey of 55 DTC genetic testing companies found that 45% of company policies contain explicit language indicating that they retain genetic data indefinitely, or until the consumer requests deletion; 11% have retention policies ranging from 2 weeks to 7 years; and 42% of policies lack explicit language about how long genetic information is retained after testing, with language implying indefinite storage. Similarly, less than half of companies surveyed (44%) address your ability to delete your data at all.

Retracting consent is sometimes impossible: If you’ve consented to share your data for research purposes, then change your mind later, you will not be able to delete your data from studies that have used that data. Once it’s been published in a journal or used for research, removing it would jeopardize reproducibility and compromise the integrity of the research/dataset.

A couple examples:

23andMe: Any research involving your data that has already been performed or published prior to your withdrawal from 23andMe Research will not be reversed, undone, or withdrawn.

Ancestry: Please note that if you have agreed to our Informed Consent to Research, we will not be able to remove your Genetic Information from active or completed research projects, but we will not use it for any new research projects.

There are legal requirements to save genetic data: The federal Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendments (CLIA) require CLIA-certified labs to store your saliva sample and DNA for a period of time ranging from 2 to 10 years. This is so that CMS can ensure that labs meet certain standards of validity and safety. Companies also state that they may retain backup copies of your data for a limited period of time.

TL;DR

DNA testing can reveal lots of interesting and useful information about you and your family. People who have gotten tested have found long lost siblings, discovered new information about their ethnic heritage, and have been able to learn if they have genetic abnormalities that put their health at risk. Not to mention, sharing data with researchers can help advance scientific research. However, the accuracy of these tests can vary by company and what you’re testing for (See: 1, 2, & 3), so you should consult with a healthcare provider or genetic counselor before taking results at face value.

This isn’t to say you shouldn’t purchase a DTC genetic test. It’s way cheaper than traditional genetic testing services, and the results can empower you with information about your health and ancestry. But to be truly empowered by your data, you need to fully understand the privacy risks that come with getting tested and/or opting to share your data.