An Introduction to Auction Theory: Blockchain Edition

Private Values

In the private values model, the value of the good is known only to each bidder and is theoretically unaffected by the signals that other bidders send, or what they believe the value of the good to be. For example, in the auction of a consumptive good the bidder values the good for the personal utility they derive from it. Some examples include memorabilia, a date with a pop star for a charity fundraiser, etc.

Interdependent Values

In the interdependent values model, bids are affected by signals that other bidders show. This stands out as a crucial difference when examining whether to employ an English Auction or a FPSB auction. Under the private values model, where bidders are unaffected by other bidders’ signals, the same strategies can be employed in each auction type. A loose example of an interdependent value auction occurs in the job market — each bidder (company) has a valuation (salary) for the good (potential hire). However, upon learning signals from other bidders (potential hire shops around the job offers), their valuations for the good may change.

Common Values

In the common values model, bidders can assume that some amount of information is shared by everyone although the exact price is unknown, like land in a known location and size but with an unknown quantity of oil beneath it, which is in essence what is really being auctioned off. One thing to be aware of in common value actions is the Winner’s Curse

By definition, the winner of a common values auction is the person who bid the most. Unfortunately in games with incomplete information, this isn’t always good news, as it’s an indicator that the winner may have overpaid. If we use the average bid as a frame of reference, then the winner’s expected value is negative. Bidders who are aware of the winner’s curse will shade their bids, meaning they will take this into account and submit something that is below their initial value.

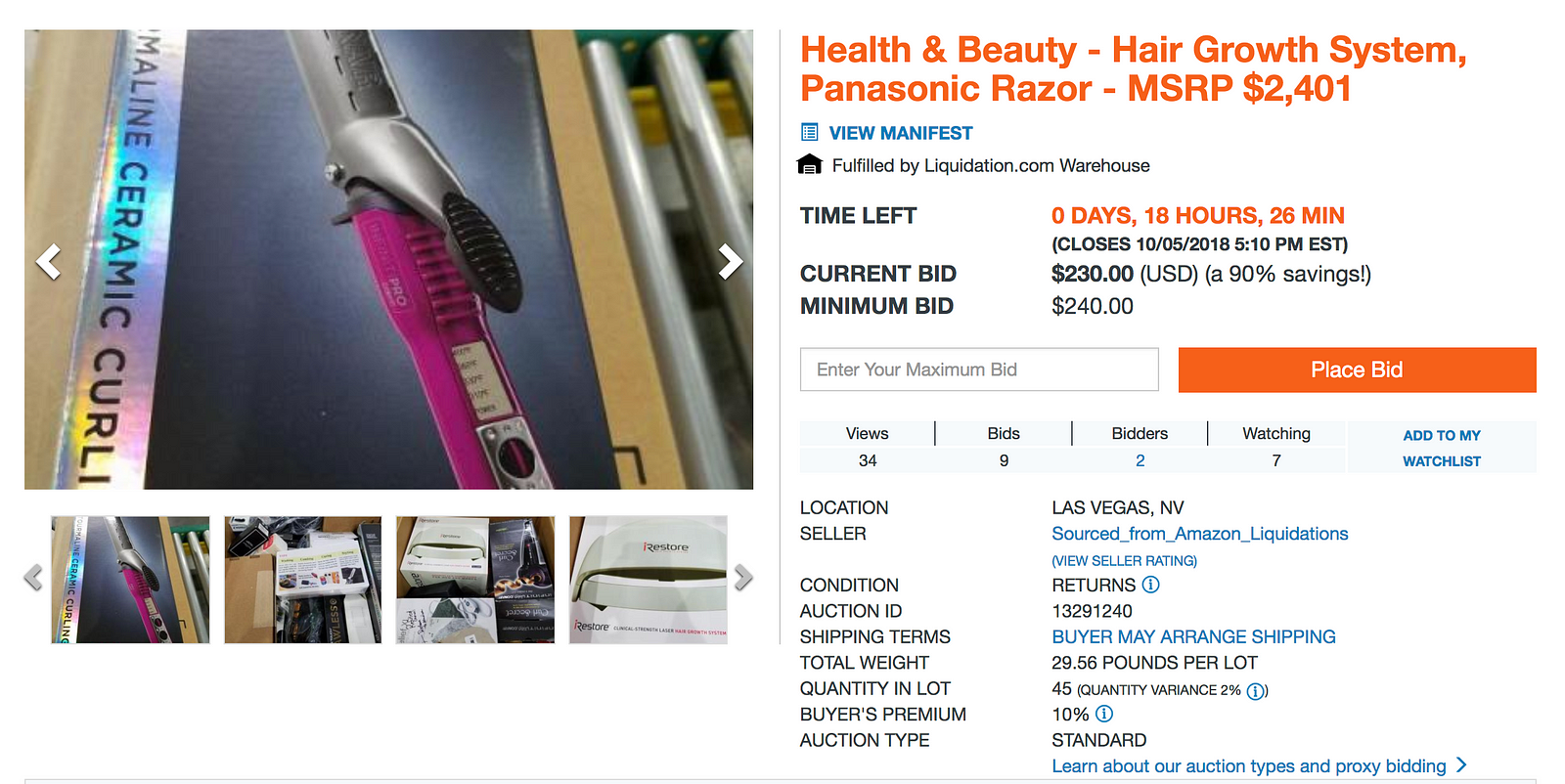

Another example of common values auctions: Amazon typically sorts returned items into categories and bundles them together in large liquidation auctions. There is a given piece of information: MSRP $2,401 which is the manufacturer’s suggested retail price. However, since these items returned, their condition is unknown… don’t you want little Stranger Hairs with the Follicle Still Attached on those returned razors?!? Some buyers may have more information than others — for example a buyer who has worked at Amazon before packaging these boxes, or buyers who have a lot of experience with purchasing these liquidation bundles. This same assumption applies to cash auctions for foreclosed homes that have an unknown amount of necessary repair.

Oftentimes when selecting auction types we tend to use revenue as the de facto indicator of efficiency. However, this isn’t always efficient if you change the audience. When public goods are auctioned into private hands, sometimes it’s better to auction it off to the person who will do the most good with it or value it the most. “Psh,” you might say, “nonsense, we can leave the market to allocate these resources efficiently. If there’s someone out there who really does value this more than the winning bidder, the winner can resell it.”

While this may certainly be the case for things like electronic goodies found inside of those sketchy looking Amazon liquidation boxes, it is not always the case. Krishna, in Auction Theory argues that post-sale transaction costs are usually high especially in the context of moves towards privatization and that private bargaining is rarely an efficient method of resource allocation. As such, even if a sale should occur, it may not.

Types of Misbehavior

Now we understand types of auctions, and can categorize items that auctions apply to, we can assess auction design mechanisms for misbehavior.

Once an auction has ended, there is an expected exchange of money and goods. However, the bidder could withhold payment and the seller could withhold the goods (in fact without an obligation to exchange goods, the Nash equilibrium here is to neither pay nor sell in which case the auction was a waste of time). This might be because the bidder regrets the bid, the seller might not have gotten a satisfactory price, or because the bidder and the seller don’t trust each other. Sometimes, sellers will hold an auction simply in order to get an idea for the price of the item without letting go of it. To prevent this stalemate, auctioneers are often used in order to ensure the transfer of goods and money.

So, we have three parties: the bidder, the seller, and the auctioneer. Each party can collude with anyone within their own party or in another party in a multitude of ways.

We’ll go over the basics of misbehavior so that we have the vocabulary to examine blockchain transaction fee economics later on!

Collusive Bidding

Collusion is rampant, and for many, the penalty for getting caught is a low probability cost to be factored into a more profitable game.

Bidders can often collude with each other to designate winners, submit phantom bids, and split the spoils. Cartels can form within auctions to suppress pricing, and these cartels can include bribed auctioneers. One example of this is in public procurement auctions where government officials (auctioneer) are bribed to allow contractors (bidders) to squeeze a higher price out of the state (seller). Several studies (1, 2) on government procurement auctions examine the effects that collusive bidding has on the price in both the short term and the long term.

Shill Bidding

Shill bidding is the submission of phantom bids with the intent to inflate the price. On e-bay, sellers may create fake accounts to make bids and drive up the price and make the auction look more competitive or legitimate to other bidders.

Transaction Fee Economics

This section assumes a basic understanding of blockchains. Check out the videos on cryptoeconomics.study for an overview

Blockchain transactions can be used for a whole host of purposes — from sending money to opening payment channels or storing data on the blockchain. Regardless of what the purpose of the transaction is, when someone sends a transaction, they care about it getting included in a block. Otherwise they wouldn’t send it. There is a private benefit to the sender for that transaction to be included but there is also a social cost to the network in including the transaction, as it must be processed by every miner, validator and full node trying to keep up with the network (Buterin, 2018).

How can we prevent things like spamming the blockchain, or random people using the blockchain as their personal hard drive? For example, the Chinese exchange FCOIN offered to list coins through implementing a voting protocol by which users send a vote (a transaction with a token that the user wants listed) to the exchange. The tokens with the highest number of votes would be listed. Unfortunately this casual incentivization of sybil attacks sent gas prices soaring on the Ethereum network, as token projects raced to be listed by blasting the network with tiny transactions. Check out this angry rant about it from MyCrypto:

Currently, transaction fees are akin to a first price auction. If the block proposer has space for 10 transactions, then those spaces will be filled by the transactions with the highest fees associated.

A sender who wants their transaction to be prioritized will attach a higher fee (painful personal flashback to a time in 2012 when I accidentally included an entire bitcoin ($15 or so at the time) as my transaction fee because I didn’t know what I was doing and wallets didn’t automatically suggest fees). But with first price auctions, there is no way to determine an optimal fee. Even if I am willing to pay $15 to ensure that my transaction gets included in the next block, if the second highest fee is only $0.10 then I could have saved $14.89 by bidding a single cent more.

Damn. If you remember what we discussed in auction types earlier, you’ll remember that first price auctions aren’t truthful. The dominant strategy is difficult to determine and relies on a multitude of factors related to network conditions and who your competition is.

What if we use uniform auctions, where all the winning bids only pay the lowest winning bid, as an alternative?

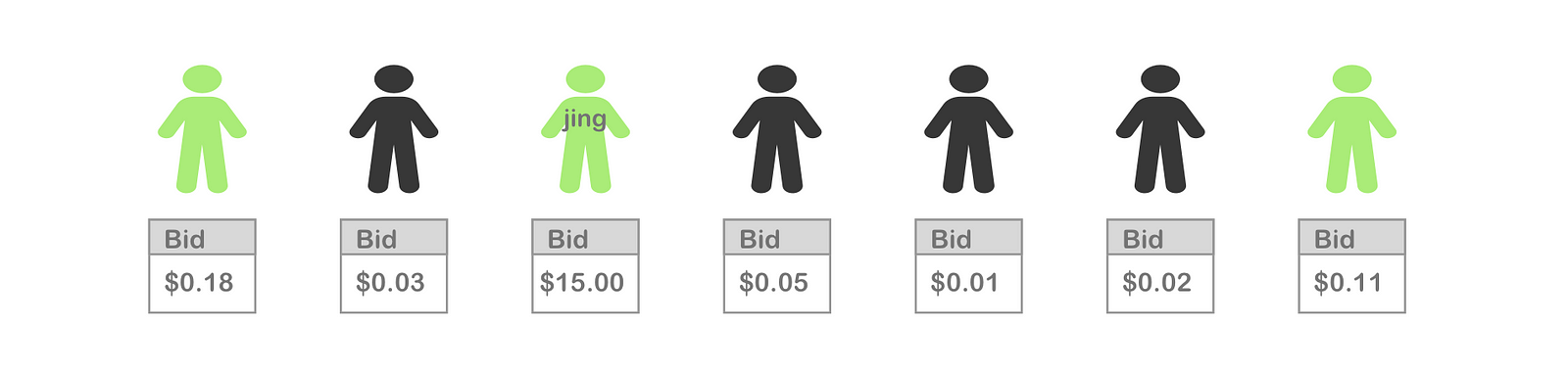

So here we have 7 bidders, but only space for 3 transactions to be included in the next block. The highest bids are colored in green. In a first price auction, the green winners would pay $0.18, $15.00, and $0.11 to get their transactions included.

In a uniform price auction, they would instead pay the lowest bid instead, or $0.11 each. That would have saved me from myself… or would it?

However, as Buterin, Kominers, et al. outline, uniform price auctions are vulnerable to shill bidding. Block proposers can “include their own transactions in a block, and thereby increase the clearing price, increasing their own total revenue… or they can collude with some portion of transaction senders, asking them to submit higher bids than their “actual” bids, and then refund them through a separate channel”.

Unfortunately, it seems uniform price auctions aren’t the way to go either.

But wait… Vickrey auctions are truthful. Why don’t we use those? Why not have a fixed fee? What about magic?

Well, fixed fees used to be an ok mechanism until transaction volume increased dramatically on blockchain networks. For a long time, transaction fees on both Bitcoin and Ethereum were pretty stable when usage was low. But hype exploded in late 2017-early 2018, and as blocks were quickly filled, competitive pricing sent transaction fees spiraling out of control.

So far, the research is leaning towards a hybrid mechanism to incentivize simplicity, more empty block space, and security.

- Simplicity: determining optimal bids with current mechanisms is complex — clients should be able to calculate this without being an all-knowing magician, and be able to bid truthfully.

- Space: establishing a minimum fee that varies per block so clients understand what it takes to make it into the next block (bid: minfee+1). Clients that don’t care as much about the transaction getting included can specify a future block to include their transactions in. Higher demand that results in blocks getting filled quickly will churn out a higher minfee in later blocks to stem the tide.

- Security: making sure that whatever mechanism is used aligns incentives as much as possible (block proposers, users, use of blockchains as public goods), and to minimize the ability to profit off of collusion.

To read more about the above points, browse through Vitalik Buterin’s draft position paper on resource pricing.

That’s it, friends! Hope you enjoyed it. And to learn more about cryptoeconomics and mechanism design for blockchains, visit https://cryptoeconomics.study/

Further Reading

Some links that I found interesting/useful/contrarian that I haven’t included already, or some super useful links that I feel should be double-posted: