Good design rules in UX design

Good design rules in UX design

There is one principle of organization that every human should adhere to, particularly people who design products. Day after day, we see companies break this rule, and it is 100% of the time to their detriment. In this article, we’ll see what that rule is, and what it means to product and service design. We’ll also raise the possible implications of this phenomenon on organizational management, collaboration, and general performance. The psychological phenomenon I will be discussing in this article is known as Miller’s Law. Rather than just tell you what Miller’s Law is, I ask you to take part in this exercise for a more immersive learning lesson.

The Exercise…

Step 1

Read the italicized instructions before starting. Grab a pen and paper. This is an exercise where you will try to recall words you’ve just read, off memory.

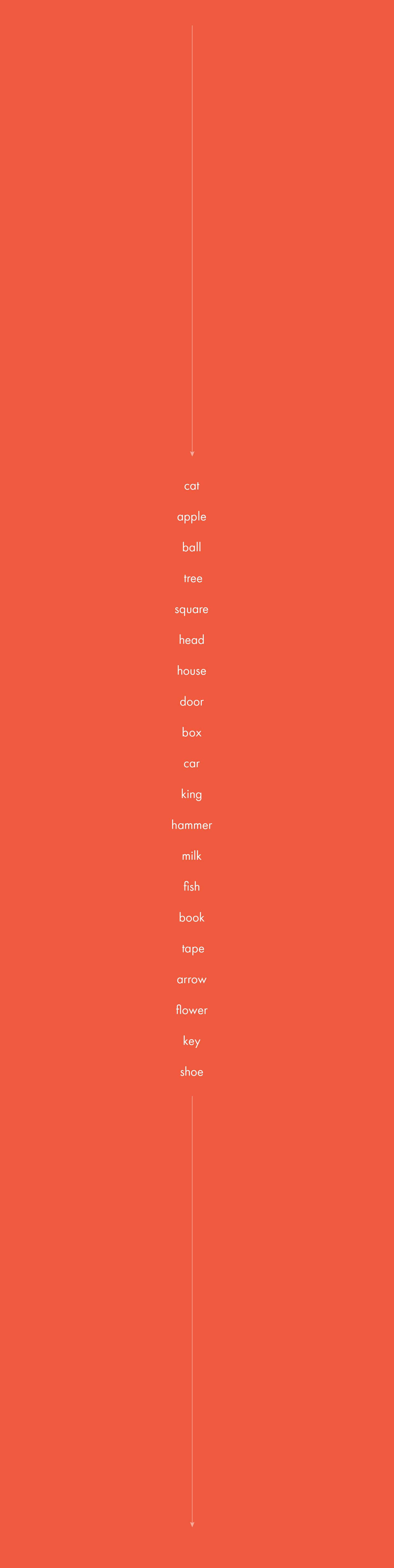

Below is a list of 20 words. Read them to comprehension , and try to memorize as many as possible. Try to keep the words ‘in your head

STOP < ··············································

Step 2

Now, use your pen and paper to write down as many words as you can remember from the list. Think hard, but

If you are like the vast majority of human beings, you will have remembered 5–9 of the words. Hundreds of experiments prove universality of this limitation on memory. When this phenomenon was first discovered, it was known to have huge implications on product design, because of the degree to which this limitation affects day to day tasks. This capacity for keeping ~7 bits of information ‘in the head’ short term, is known as Miller’s Law.

Miller’s Law — The Magic Number

In 1956 there was a paper written that became one of the most highly cited papers in psychology. Titled, The Magical Number Seven, Plus or Minus Two: Some Limits on Our Capacity for Processing Information, it was published in 1956 by the cognitive psychologist George A. Miller of Princeton University’s Department of Psychology in Psychological Review. The crux of the paper suggests that the number of perceptual ‘chunks’ an average human can hold in working memory (a component of short-term memory) is 7 ± 2. This is frequently referred to as Miller’s law. Here is a summary of the article, sourced from wikipedia:

In his article, Miller discussed a coincidence between the limits of one-dimensional absolute judgment and the limits of short-term memory. In a one-dimensional absolute-judgment task, a person is presented with a number of stimuli that vary on one dimension (e.g., 10 different tones varying only in pitch) and responds to each stimulus with a corresponding response (learned before). Performance is nearly perfect up to five or six different stimuli but declines as the number of different stimuli is increased. The task can be described as one of information transmission: The input consists of one out of n possible stimuli, and the output consists of one out of nresponses. The information contained in the input can be determined by the number of binary decisions that need to be made to arrive at the selected stimulus, and the same holds for the response. Therefore, people’s maximum performance on one-dimensional absolute judgement can be characterized as an information channel capacity with approximately 2 to 3 bits of information, which corresponds to the ability to distinguish between four and eight alternatives.

Moreover, the human mind can remember ~7 bits of information when completing a task that requires cognitive effort. This is critical, because humans are constantly performing tasks, and trying to juggle various stimuli in the mind when doing so. One of the key concepts behind Miller’s Law is ‘chunking’, which basically means assembling various bits of information into a cohesive gestalt. For example, the word · p e n c i l · is actually a ‘chunk’ of letters, organized into a perceptual gestalt. If the letters were rearranged · c n l i p e · it would be six separate chunks of information. Chunking is a critical element of information organization, and is the basis for our UX and organizational rule.